We Need to Stop Shaming Black Artists Like Drake for Being ‘Too White’ (Opinion)

By Jeremy Helligar

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – “Black-ish” with an upper-case B is an African-American sitcom loved by both black and white viewers. But “black-ish” with a lower-case b doesn’t always fly with African-Americans when it comes to their tunes.

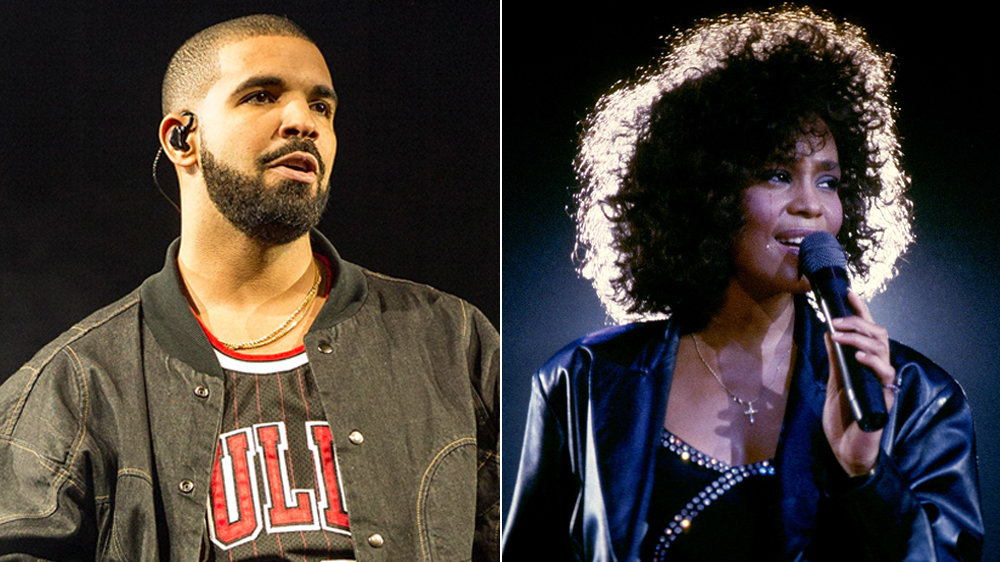

In both forms, the word refers to a lack of black cred, whether it’s for talking too white, acting too white, or being too white, accusations Drake haters have hurled at the rapper since he hit the hip hop scene. Some in the African-American community criticize him for making music that’s as much pop as hip hop and promoting a soft image. In other words, he’s not “black” enough.

Still, is arguably the most successful rap star of the past five years. On June 29, his fifth studio album “Scorpion” set a Spotify record for the highest number of global streams (132,384,203) in a single day. Over the course of the sprawling 25-track double album, Drake raps about love, himself, fame, himself, his baby boy, and himself.

If you prefer your rap with Kendrick Lamar and J. Cole-style social commentary, “Scorpion” probably will sting you the wrong way. The biracial Canadian rapper born Aubrey Drake Graham does, however, address his not-“black”-enough critics on “Nonstop,” the album’s best track.

“Yeah, I’m light-skinned, but I’m still a dark ni**a,” he raps, defiantly and defensively.

Drake’s race dilemma echoes that of another crossover star who hit her commercial peak 30 years ago. Two recent documentaries on the late Whitney Houston touch on the singer’s issues with race and identity in the years before her death in 2012. Last year’s “Whitney: Can I Be Me” and “Whitney,” which came out on July 6, both address the criticism Houston endured early in her career for what some blacks perceived as her white, Cinderella-ish image.

The earlier documentary goes so far as to link her being booed at the 1989 Soul Train Music Awards to her long downfall. The shade was thrown when James Ingram and Heather Locklear (!) were announcing the nominees for Best R&B/Urban Contemporary Single/Female, an award Anita Baker won.

Hurt by the jeers, Houston may have felt she had something to prove, and “Whitney: Can I Be Me” suggests she got involved with Bobby Brown to prove it. The pair met that night, and their messy, volatile marriage, which was marred by domestic violence and drug abuse, coincided with the start of Houston’s downturn.

While it might be a stretch to blame her death on Brown, the black community, or even the claim in the recent “Whitney” documentary that she was sexually abused by her cousin Dee Dee Warwick, it’s hard to understand why, for her “too white” detractors, her talent wasn’t enough. Coming at the end of a decade where Michael Jackson’s record label, CBS Records, had to threaten to pull videos by all of its artists from MTV if the network didn’t start playing clips by the world’s then-biggest star, why couldn’t we celebrate the success of a black woman unconditionally? Why did it matter that she didn’t sound as “black” as Stephanie Mills, Chaka Khan, or Anita Baker? The fact that those talented ladies never scaled the commercial heights that Houston did says less about them than it does about a white America that still wasn’t ready to fully embrace the sounds of blackness.

Sadly, the hot and cold reaction to Drake is an indication — just one indication — that we haven’t evolved much since Houston was booed nearly 30 years ago. But even if Drake’s hip-hop swagger is just a performance, a ploy to be less black-ish, he deserves credit for keeping the content of his music real. While he may have faced a certain degree of racism as a biracial actor in Canada — he’s said that the shocking 2007 photo of him wearing blackface, exploited mercilessly on social media by Pusha T during their recent feud, was commentary on racism in the acting industry — do we want to hear him rapping about a black experience he never actually had?

Songs like “Hotline Bling” and “Nice for What” may never win Drake a Pulitzer Prize, but they continue a longstanding tradition of music being purely for entertainment. Even the most acclaimed rap hasn’t always tackled politics or social issues directly: In the 1980s, when Run-DMC was rapping about “Hard Times” and documenting life in black America, LL Cool J became a star rapping about how he couldn’t live without his radio.

His hits were never particularly political or socially aware, but did the rap ballad “I Need Love” and the frat anthem “Going Back to Cali” escape “too pop” ridicule because he never quite reached the commercial heights of Whitney, or MC Hammer? It makes one wonder what would have happened if LL’s “Bigger and Deffer,” “Walking with a Panther,” and “Mama Said Knock You Out” albums had each sold the 10 million-plus that “Please Hammer, Don’t Hurt ’Em” did.

Drake is not the incisive social poet that Pulitzer winner Lamar is. He spends much of “Scorpion” griping about how tough it is to be rich and famous, as Houston infamously did on her flop 2002 single “Whatchulookinat.” Still, to quote Bobby Brown, it’s his prerogative to be as “shallow” and “superficial” as he wants to be. If that makes him too pop, too white, too black-ish, there are worse things for a music superstar to be.