Venice Film Review: ‘Shadow’

By Jessica Kiang

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – Black ink drips from the tip of a brush and daggers into clear water, spiraling out like smoke; a Chinese zither sounds a ferocious, twanging note that warps and buckles in its sustain; rain mottles the sky to a heavy watercolor gray, forming pools on paving stones into which warriors bleed; whispery drafts from hidden palace chambers stir tendrils of hair and set the hems of luxuriant, patterned robes fluttering. Every supremely controlled stylistic element of Zhang Yimou’s breathtakingly beautiful “Shadow” is an echo of another, a motif repeated, a pattern recurring in a fractionally different way each time.

After 2014’s semi-autobiographical “Coming Home,” which had soul but little spectacle, and 2016’s “The Great Wall” — all spectacle and no soul — it seemed like the Himalayan peaks of the revered Fifth Generation filmmaker’s career (“Raise the Red Lantern,” “Hero,” “Red Sorghum,” “House of the Flying Daggers”) might now be behind him. But here, almost insouciantly and with little fanfare, comes “Shadow,” a thrilling return to form, which matches Zhang’s best work for the sheer voracious elegance of the images and possibly surpasses much of it for inventiveness. Most strikingly, in styling the locations and costumes almost entirely in black and white, but shooting (alongside regular DP Zhao Xiaoding) in color, Zhang, famous for his lantern reds, golden yellows and the soft, pretty pastels of “Flying Daggers,” gives the whole film a monochromatic sheen, highlighting only the skin tones of the characters and the dark crimson of the blood they spill.

Based on the fabled “Three Kingdoms” saga of Chinese legend (with China having such “a long historical past,” said Zhang in interview, “I wouldn’t create baseless stories”), “Shadow” is a knotty tale of palace intrigue, old grudges and crafty doppelgangers, that can take a minute to get a proper hold on. In the court of the Pei Kingdom, ruled by a seemingly petulant and cowardly King (Zheng Kai), the noble and brilliant Commander Yu (Deng Chao) counsels war against a powerful neighbor who has captured the strategically important city of Jingzhou. The King ignores his advice, preferring to sue for peace with the invaders and even offering them his beloved sister (Guan Xiaotong) in marriage to seal the craven alliance. Yu nonetheless arranges a one-to-one duel with the legendarily unbeatable spearsman General Yang (Hu Jun), the leader of the invading forces who inflicted a terrible wound on him the last time they met, to decide the fate of the city.

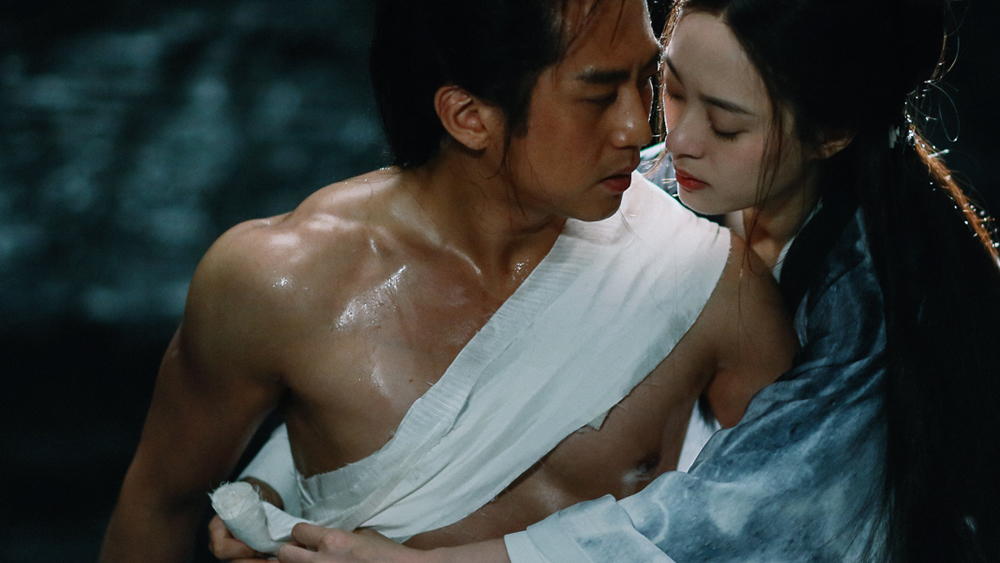

But the Commander is not who he seems to be: Really he is the low-born Jing, who was plucked from poverty as a child due to his resemblance to Yu, and trained to be his double, or “shadow.” The cunning but ailing Yu has gone into hiding in the palace’s secret chambers, and with the collusion of his resourceful wife Madam (Sun Li), Jing has taken his place at court, fooling everybody.

It’s an absorbingly epic yarn, and though often talky, there’s always something in restless motion — a beaded headdress or a capacious sleeve — making even convoluted, exposition-heavy sections feel visually dynamic. Really the story lives in its staging and shotmaking: It billows to life in the flooding liquid silks of Chen Minzheng’s sumptuous costuming, the enviable fabrics printed in an abstract, stained water motif (if Zhang ever thinks to launch a pret-à-porter line — and by all means let’s encourage that — he’s already got the designs in hand). And it thrums through Ma Kwong Wing’s amazing production design: The elaborate, monochrome interiors, full of secret spyholes and gauzy, blurring screens, and the permanently rainswept, slicked-down exteriors give the film the look of a graphic novel painstakingly drawn in classical Chinese ink-brush technique.

But there’s more than just beauty in this tall twisted tale of power plays and divided loyalties; there’s wit, too. Madam has grown closer to her husband’s surrogate and further from her husband, and while Jing duels for the fate of the city, she duets with Yu in a zither pas de deux, which is just as thrillingly adversarial (indeed, the flutes-and-lutes of Loudboy’s classical Chinese score are perfect accents to the action throughout). And when Madam has a stroke of inspiration about how to combat the enemy’s mighty, thrusting-spear technique that involves using a parasol as a shield and moving in a graceful, “feminine” sway, the technique is adopted by the Pei troops, though modified, so the umbrellas are now edged in sharp metal and send blades slicing through the air when twirled. During one particularly crazy sequence that should be credited to action sequence designer Dee Dee, a detachment of soldiers, each nested into an upturned umbrella, is catapulted, spinning like the teacups in Disneyland’s Mad Tea Party, down the waterslide of a rain-soaked city street: It may not be the most thematically weighty of art-house films, but the cinema of “Show me something I’ve never seen before, and make it heart-stoppingly beautiful” has in “Shadow” a new title for its pantheon.