Tribeca Film Review: ‘I Want My MTV’

By Owen Gleiberman

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – The first thing you want from a history of MTV is to get dunked in the hot-but-cool nostalgia of it, and the fast, fleet documentary “I Want My ” delivers those 1980s goods about as good as you can get. Here’s “Video Killed the Radio Star,” the novelty single by the Buggles that launched the channel on Aug. 1, 1981 — a tune that, in hindsight, sounds as sing-song catchy in its percolating bliss as a Divertimento by Mozart. Here are the five original VJs — shaggy Mark Goodman, earnest Alan Hunter, snarky Martha Quinn, jovial J.J. Jackson, and hipstery Nina Blackwood — fumbling around against a set that looks more like Wayne Campbell’s basement than a television studio, tossing off we’re-making-this-up-on-the-spot-and-we-know-it patter that became the casual formative version of “attitude.”

Here are those primitive early days when for every music video that was made with flair, like the S&M-flavored Old West Reagan Americana panorama of Devo’s “Whip It,” there were four that were chintzy and Scotch-taped together, from the rocker-dudes-with-mullets-standing-at-the-mic drab corniness of REO Speedwagon’s “Take It On the Run” to the home-movie-shot-in-10-minutes-between-takes-in-the-recording-studio vibe of early Police videos. Here are the image revolutionaries, the geniuses of striking a pose, like Madonna and Boy George, and here are the controversies, like the fact that MTV treated videos by African-American artists as if they’d crashed in from another planet.

And here, after the network had been around for a few years, is MTV’s exquisitely tuned promotion-or-rebellion? self-referentiality: the videos, in their yummy profusion, meets the attitude, in its loose-limbed superiority, meets the sheer addictive never-endingness of it all. It all added up to a new definition of the metaphysics of youth diversion.

I didn’t get ready access to MTV until I moved into my own place for the first time, in the fall of 1983, and though the network was only two years old, it felt like I was a decade late to the party. All the MTV I’d missed! But I made up for lost time. The not-do-dirty secret of MTV is that it was a clubhouse not just for teenagers or college kids but for a generation of arrested adults. It was more than something you consumed — it was a place you went. It worked fine as background wallpaper, but when you really sat down and plugged into it, you were a kid in a candy store (an eye-candy store), gorging on a new way of being.

The irresistible fun of “I Want My MTV” is that the documentary’s directors, Tyler Measom and Patrick Waldrop, do such a nimble and straight-up job of filling in the backstory of how it all happened. They sketch in the world before MTV, when music videos were bubbling up in the culture but remained off the radar and nearly underground. It’s not as if anyone was hiding them, but where could you see them?

We all know that the Beatles, in tandem with director Richard Lester, invented music video — in “A Hard Day’s Night” and “Help!” (and even more so, without Lester, in the surrealist rock dreams of “Magical Mystery Tour”), and in the early promotional clips they made for tracks like “Strawberry Fields Forever.” There are other building-block versions of the form, but “I Want My MTV” puts its finger on “Rio,” a 1976 video by Michael Nesmith of the Monkees, as the Rosetta Stone of what became MTV. Nesmith and his collaborators, drawing on the camp sensibility of “The Monkees,” found their way to a rapidly shifting mode of free-form kitsch that became the template for much of what came afterward.

A show called “PopClips,” developed by Nesmith as a promotional vehicle for the Warner Communications record label, was the direct precursor of MTV, debuting in 1980 (though the show in New Zealand that inspired it, “Radio with Pictures,” premiered in 1976). The filmmakers interview all the executives — like MTV’s founding programmer and CEO, Robert W. Pittman — who convinced the powers at Warner-Amex Satellite Entertainment that a 24-hour music channel was the way to go. These were hip geeks whose instinct told them they were putting together something that was meant to be. Yet none of them really knew what it would be.

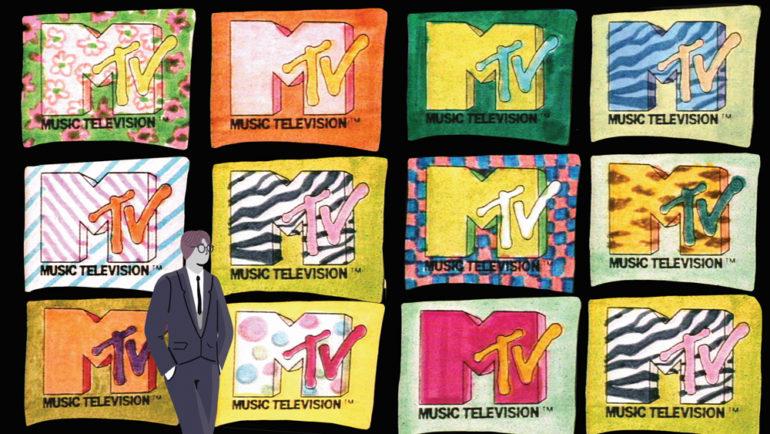

From its scrappy early days, MTV was a fusion of happenstance and necessity-as-the-mother-of-invention. The logo was found on a crumpled-up, discarded piece of paper at the bottom of a pile of proposed logos; the beauty of it is that it would prove infinitely malleable. The decision to use NASA footage in the interstitial promos was based on the fact that it was in the public domain (and would therefore cost nothing!), but what a master stroke that proved to be. It ended up defining MTV’s audacity as the moon shot of the John Hughes generation.

And then there was the fact that MTV nearly went under. In the early ’80s, cable TV was still in its toddler phase (basically, it consisted of CNN, HBO when it was just movies without commercials, and a network devoted to non-blockbuster sports called ESPN). When MTV was born, you couldn’t even get it in New York City (the executive team had to go out to a bar in Fort Lee, New Jersey, to watch the launch), and cable, more than now, was a market-by-market business. The local operators were Middle American fuds who didn’t understand MTV and didn’t want it on their systems. How to convince them?

George Lois, the advertising legend of the ’50 and ’60s, was hired to accomplished this, and he came up with the idea of doing a variation on the “I want my Maypo!” campaign that had been used to sell the iconic cereal brand in the ’60s. It was Les Garland, the network’s new senior executive vice president, who convinced the rock stars to sign on. Garland was friendly with Mick Jagger and flew to London to see him, asking him to say, on camera, “I want my MTV!” He did the same thing with Pete Townshend. He had to twist their arms a bit (and Townshend twisted his delivery for maximum irony), but it was one of the greatest coups in advertising history, encouraging a nation of couch-potato youth to literally call their cable companies and badger them into adding MTV. (The key aspect of the slogan was that it was “my MTV.”) The rock stars weren’t paid, so why would they exploit their own images to sell MTV? Because maybe they didn’t realize how much that four-word pitch would redefine them. Or, then again, maybe they did.

MTV’s stratospheric success made it, for years, a happy story, but “I Want My MTV” doesn’t soft-pedal the accusations of racism that dogged the channel. Its defense — or, at least, explanation — for why so few videos by black artists were in the mix goes back to the historical racism of the music and radio industries, with “rock” and “R&B” segregated into separate categories. As false a division as that always was, it was seen, at the time, as the conventional demographics of mainstream taste. Yet the notion that MTV would run all the cheesy, fourth-rate videos they did and have an issue with Rick James’ “Super Freak” because it wasn’t “rock” is, in hindsight, ludicrous and disgusting.

It was the supernova of Michael Jackson that came to the rescue (the channel couldn’t have survived without programming him — though for a while it tried). But then MTV went through the same thing all over again with hip-hop, ignoring the form only to discover that rap could be its new cutting edge. It’s a bit outrageous to view all this from the standpoint of 2019, when pop music by African-American artists hovers over what’s left of the tattered shards of “rock.” But Darryl McDaniels, from Run-D.M.C., adds a brilliant perspective on the subject, and the fact that MTV’s sins were rooted in those of the music business at large is a fair point to make, even if no one’s pretending that it’s an exonerating defense.

“I Want My MTV” catches you up in the heady days when music video (“Money for Nothing,” “Express Yourself,” “When Doves Cry,” “Take On Me”) was becoming an art form. The movie is also honest about how, by the late ’80s, samey-same pyro-and-babes metal videos were starting to turn the network to sludge. The filmmakers are right to focus on the first seven or eight years, when MTV reordered the DNA of youth culture. But what was it about a channel that showed one music video after another that made it seem…revolutionary? Maybe it’s that all those videos felt so much greater than the sum of their parts. There was a romance to MTV. It was the pop musical that never ended, though at the center of the kaleidoscope was something unseen yet omnipresent: us. We wanted our MTV because we completed it.