Toronto Film Review: ‘Quincy’

By Andrew Barker

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – There’s a startling moment late in “Quincy,” Rashida Jones and Alan Hicks’ Netflix documentary about the octogenarian music man Quincy Jones, in which our subject takes an early tour of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History & Culture, whose imminent grand opening ceremony he’s spent the last few months planning. Stepping out of his wheelchair, Jones takes a slow ramble through the museum’s music wing, pausing to take in the glassed-off personal effects of the people he calls “all the old homies”: Ray Charles, Michael Jackson, Dinah Washington, Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis – each and every one of them among Jones’ onetime friends and collaborators, and each and every one of them now dead. For the first time in the film, Jones appears to be at a loss for words. It’s one thing to play an indispensable role in more than half a century of musical history, but it’s quite another to live long enough to see that history literally enshrined in the Smithsonian.

For those unfortunate souls who only know Jones as the producer of “Thriller” or, more recently, a giver of deliriously entertaining interviews, “Quincy” presents a streamlined and convincing case for taking a much deeper dive into his accomplishments. Conventionally structured and generally valedictory, the film makes no bones about its all-in-the-family origins: Hicks most recently directed the Quincy-produced documentary “Keep on Keepin’ On,” while is, obviously, his daughter. The filmmakers’ closeness to their subject presents a series of trade-offs. It’s unlikely, for example, that a less-connected director would’ve been on-hand in a hospital room to capture Jones’ reactions as he emerges from a diabetic coma in 2015. (He initially seems disoriented, until a doctor asks him who the president is. “Sarah Palin,” he responds, flashing an invisible smirk.) But one can’t help but wonder if a more objective hand would have revealed more by pushing him further.

Later on, the film will detail the punishing work ethic that allowed Jones to stay on top for so long, but as it begins, he seems content to be enjoying his status as a living legend. The film’s opening stretch offers a blur of footage of the eminence grise as he makes the rounds from one party to another, with figures like Paul McCartney, Beyonce, Willie Nelson, Lady Gaga and Herbie Hancock all lining up to pay homage and deliver a hug or a fist bump. His daughter greets him with her camera rolling as he climbs into the back of a car after the latest soiree, chuckling at the pace he’s keeping. “I can party all day,” he says. “Never bothered me.” Minutes later, the screen goes black and we hear a 911 recording — in the next scene, Jones is in the hospital.

From here, the film vacillates between intimate home footage of Jones trying to get back into shape and coming to grips with his close call – with all of the professional demands of being rarely allowing him enough room to breathe – and history lessons that move decade-by-decade through his life via dips into Jones’ personal film and photo archive. The film’s two interwoven halves rarely seem to be in dialogue with one another, however, giving the documentary a degree of disconnectedness as it toggles back and forth.

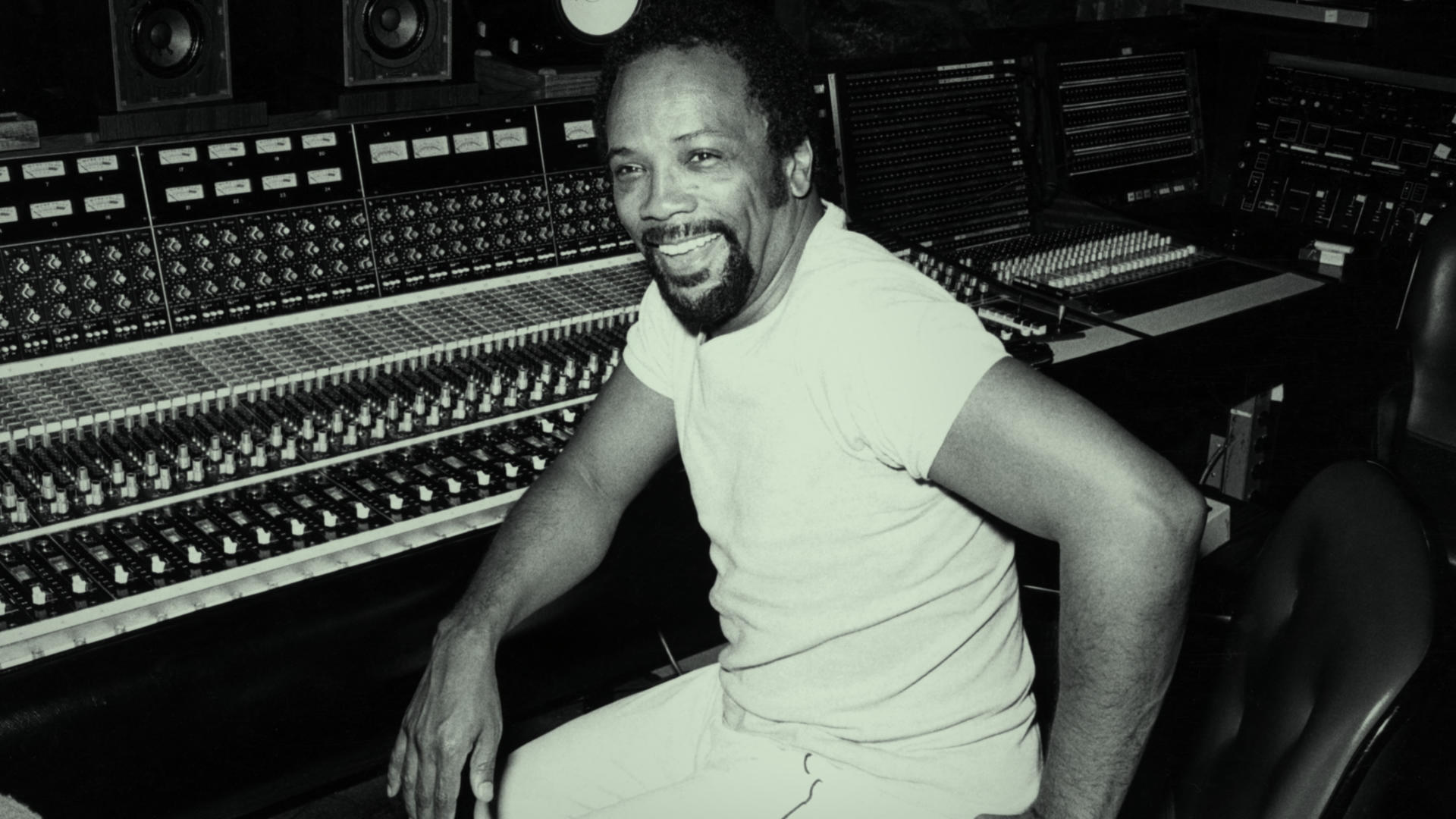

For anyone who’s already familiar with Jones’ career, few of the milestones discussed here will be new, but the plentiful footage Jones and Hicks unearth brings welcome life to what could have been a staid highlight reel. We see photos of the very young Jones in his bleak old neighborhood of Chicago, where he endured the Depression at its worst. We glimpse him in black-and-white footage as a baby-faced teenage trumpeter playing with Lionel Hampton, the first wisps of a mustache on his lip. We watch when he’s singled out onstage by Frank Sinatra, serving as the Chairman’s twentysomething arranger in the mid-’60s. We follow him poring over film reels and jotting down melodies as he makes a name for himself as a film composer, becoming one of the first black musicians to do so. And of course, we get to see him in the studio with Jackson, whose astronomical solo success under Jones’ auspices turned the already-plenty-famous producer into a genuine international celebrity. Hanging around on set as Jackson shoots the “Thriller” music video, a cocky Jones predicts it’ll one day be regarded as the “Citizen Kane” of the young form – when you’re right, you’re right.

Stretching to more than two hours, “Quincy” stumbles into some pacing problems as it goes, and considering the sheer number of turns the man’s life took, one wonders if a miniseries might have served him better. It would be great, for example, to learn more about Jones’ career evolution in the 1990s, when he launched ambitious ventures like Qwest Broadcasting and Vibe magazine, and attempted – not always successfully – to play an elder statesman role to the hip-hop generation. Indeed, even Jones’ most challenging moments (multiple divorces, a nearly fatal brain aneurysm in the 1970s) are generally treated to a sanguine sheen.

But there’s one trauma that even the effortlessly witty, avuncular Jones can’t quite shrug off. He’s eager to tell old war stories about his rough upbringing in Chicago, showing off the scars on his hand from a childhood stabbing while Dr. Dre looks on. But he also carries a far deeper scar from his youth that doesn’t make for such easy conversational fodder: his mother was schizophrenic, and Jones has very clear memories of watching her as she was dragged away in a straitjacket when he was only seven. It’s hard to fathom what that sort of experience would do to a child, and Jones’ tears come quickly when he finally revisits their old home in the late 1980s. It’s a reminder that beyond all of the quips and hits, there’s a deep, complicated man beneath that even a film this ostensibly intimate can’t quite manage to encompass.