Toronto Film Review: ‘Baby’

By Maggie Lee

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – A nuanced film examining the consequences of China’s one-child policy, “Baby” follows a woman abandoned at birth trying her utmost to save an infant girl left to die by her parents. Devastating yet brimming with tender compassion, the film is a veiled critique of the rigidity of Chinese state welfare, discrimination of women and the disabled, and how kindness nonetheless survives in a harsh world. Writer-director Liu Jie’s vérité style captures China’s new working-class milieu, imbuing the gripping plot turns with gritty authenticity.

With “Baby,” Liu completes his trilogy of litigation-themed films — preceded by “Courthouse on Horseback” and “Judge” — which explored the discrepancies between the letter and the spirit of the law. As in those two earlier features, Liu bases his screenplay on real-life characters. The social background dates back to the late ’90s, when the steep rise of orphans (the majority being girls or babies with medical defaults) forced the government to pay poor families to provide foster homes for some of them. The Chinese title “Baobei,” which means “treasure” and is a common term of endearment for children, is therefore bleakly ironic.

At the heart of this tragedy is an ethical tug of war between universal human rights upholding the autonomy of the individual and the Chinese Confucian conviction that parents have God-given control over their children, from how they live their lives to their right to exist. The political subtext is that by extension, this patriarchal tradition also confers rulers with absolute power over their citizens.

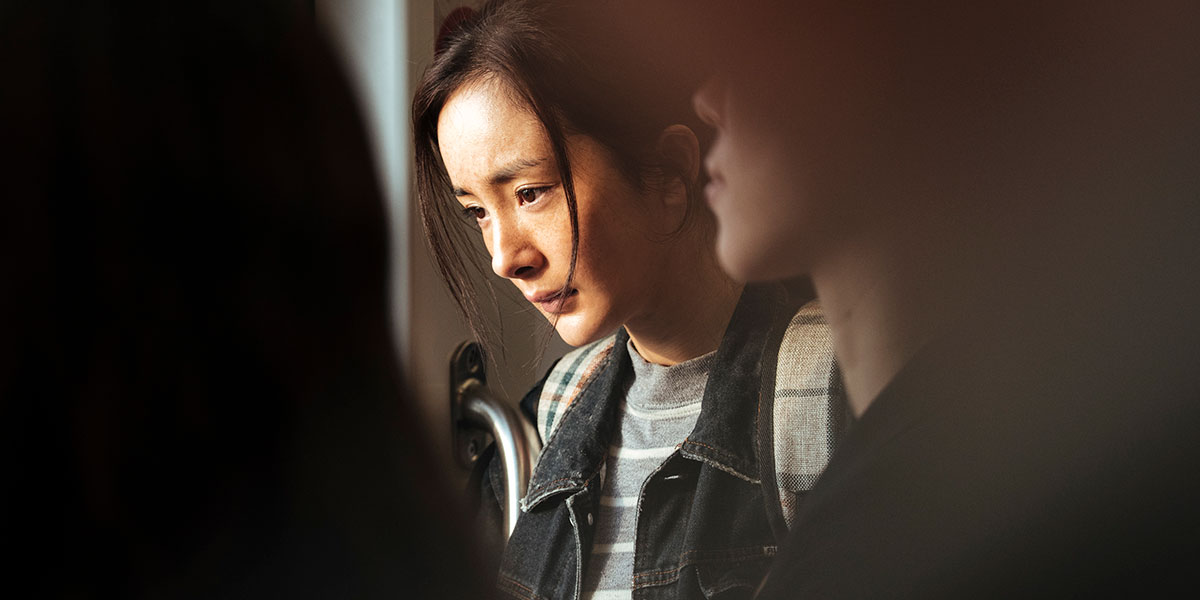

Jiang Meng (A-lister Yang Mi, a.k.a. Mini Yang) is about to turn 20, which means that by law, she has to move out of her foster family’s house on the outskirts of Nanjing. Since she doesn’t want to send her widowed mother, who is old and in ill health, to a retirement home, she needs to get a better paying job so she can continue to care for her. Abandoned at birth, Meng suffers from a congenital illness which led to numerous grueling operations throughout her life. This means she could neither pursue higher education nor take up physically demanding work. Her best friend Xiao Jun (Lee Hong-chi, “Thanatos Drunk,” “Long Day’s Journey Into Night”) and his other hearing-impaired buddies urge her to sign up for disabled welfare, but she’s too proud and principled to do that.

Meng overcomes considerable discrimination to get hired as a cleaner in a hospital. One day, she encounters a baby girl in her ward who suffers from the same condition she does. When she overhears the father choosing to let his newborn child die rather than try out the treatments recommended by the doctor, nothing can stop her from saving this fragile life. While Meng’s reaction, which includes sneaking into a hospice to kidnap the baby, seems impetuous and self-righteous at first, it gradually transpires that she is not merely venting her own resentment against irresponsible parents. She comes to symbolize a humanitarian argument for the value and resilience of life, serving herself as proof that survival is possible against all odds.

However, when she finally succeeds in bringing the law and public opinion to bear upon the father, his arguments for the decision come as a big surprise for her, as well as the audience. Throughout Meng’s impassioned battle for justice, the unpredictable fate of the baby is fuel for truly polished psychodrama. As she tries to mobilize policemen, doctors, social workers, and even her disabled friends (who are too disadvantaged to spare any more compassion), the audience can feel how their consciences are genuinely stirred, but they are helpless under an uncaring state system.

Her trajectory parallels those in Zhang Yimou’s “The Story of Qiu Ju” and Feng Xiaogang’s “I Am Not Madame Bovary” with one significant difference: Liu is a lot less cowardly than Zhang or Feng, who purport to satirize government bureaucracy, then try to cover their tracks by making fun of the female protagonists’ pigheadedness, and belittling their court cases, which are made to seem petty. In “Baby,” however, there is no question about the seriousness of what’s at stake, and Liu pulls no punches in exposing the widespread economic hardship or how Chinese society discriminates against women and the disabled, exacerbated by the one-child policy.

Of equal weight is Meng’s painful struggle to stay by her mother’s side. Liu deliberately shows them brawling all the time. It’s a particularly Asian way of behaving to closest kin — there’s no wall of politeness between them — and precisely because they care so deeply, they pretend not to need one another in order to free each other from the perceived burden of familial duty. Chinese law may keep them apart by citing the technical difference between adoption and foster care, but the film movingly demonstrates that love has no judicial or biological boundaries. And yet, the social realities that press on the protagonists ultimately offer neither comfort nor catharsis.

Yang, despite being a surefire box-office guarantee, has never been associated with good acting (in fact, as leading lady of the “Tiny Times” franchise, one of the most successful YA films in China’s history, she was handed the Golden Broom Award for “Most Disappointing Actress”). Here, she undergoes a miraculous transformation, losing her vacuous prettiness to portray a brittle, harried working-class woman prematurely aged by ill health and poverty. Learning the Nanjing dialect and sign language seem to have taken the place of her trademark ditzy schtick and simpering tone of voice. Similarly, playing a deaf-mute resolved the problem of Lee’s Taiwanese accent, allowing the actor to blend in with the local cast, made up of non-pros who play their own professions as police, medical staff, or social workers.

Tech credits are polished despite the grungy texture of Florian Zinke’s cinematography. Racy editing by two masters, Taiwan’s Liao Ching-song and Hong Kong’s William Chang, bring out the story’s emotional intensity without slipping into sentimentality.