‘The Present’: L.A. Theater Review

By Peter Debruge

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – Before the coronavirus pandemic forced us all into isolation, Donald Trump told America, “It’s going to disappear. One day, it’s like a miracle, it will disappear.” Well, in the absence of a miracle, or medicine, the next best thing we can count on is magic, and while it won’t beat COVID-19, Portuguese illusionist Helder Guimarães’ one-man sleight-of-hand show “The Present” sure makes isolation a lot more bearable.

Last year, Guimarães debuted an intimate monologue called “Invisible Tango” at Los Angeles’ Geffen Playhouse, performing card tricks for crowds of no more than 100 guests on the theater’s smaller stage. Now, reteaming with director Frank Marshall for an inspired reaction to exceptional times, he and the Geffen have hastily pulled together a program uniquely suited to the present moment in which magic works remotely, overcoming social distancing to create a communal sense of shared awe and connection.

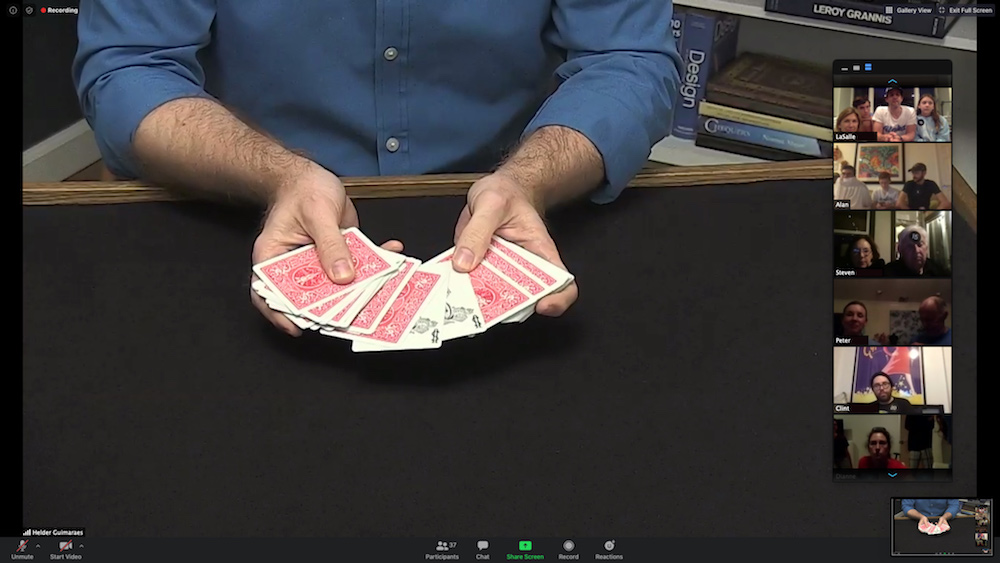

Instead of buying seats, audiences pay for a place at the virtual table, tuning in via Zoom for a live stream. But even though attendees — which are capped at 25 households per show, with no limit to the number gathered behind each screen at home — are physically distanced from one another, this is no passive theatrical experience. Your ticket comes with more than just access: Each ticket also includes a small cardboard box, tied up in twine and mailed to everyone’s home address, which contains a deck of Bicycle cards and several other props for remote participation.

Once all the guests have gathered in their respective windows on Zoom, the host instructs them to switch to “Speaker View,” which trains our attention on Guimarães, who enters as casually dressed as any magician I can recall — his blue button-down untucked, sleeves half-rolled — in what appears to be his study (but could be just a set). In theory, watching magic at a moment like this might seem corny, but Guimarães makes it personal from the outset, explaining how his love of card tricks traces to a time he spent in quarantine at age 11. After being hit by a car, young Helder slipped into a coma and then, once revived, recuperated at home, accompanied by his grandfather, who becomes a recurring character in his stories.

Guimarães is slightly built and vaguely awkward in his body language, which has the rather charming effect of making his show feel less polished than it actually is. He comes across like those teenagers who’ve just discovered magic and want to demonstrate their new skills to anyone curious enough to indulge him — which, in the memories he shares, is exactly what he was, although he’s had decades to perfect his routines. First, he performs a few tricks alone on his end, but once the audience has adapted to his style, he instructs them to open the Bicycle decks he sent them and proceeds to instruct the at-home viewers to pick and shuffle cards on their end, correctly predicting (with about a 75% accuracy) the top card in each of their hands.

My own card was among the ones he guessed wrong, but given my distraction (toggling the screen controls on my computer, taking notes on the experience), that’s surely the result of something I flubbed on my end. In future tricks — those involving a word-find puzzle and other card-based gambits, all tied together by sentimental anecdotes — the results went Guimarães’ way. With each surprising outcome, I could feel the collective awe building among my fellow viewers. Here we were, separated by who knows how much distance, united by a common sense of “how’d he do that?”

As someone who’s spent the last two months in virtual isolation, interacting with no one but grocery store clerks and take-out handlers, there was something undeniably moving about the experience, which made me treasure my usually anonymous role as part of an audience. When I go to the theater, I like to disappear into the dark, dreading the idea that a magician or comedian might single me out. If a performer calls for a volunteer, I try to make myself invisible.

But this was different. Each household was given a number with their box, and at times, Guimarães would pluck one from a wine glass and ask for us to shape the fate of his next trick. On Zoom, that feels less intimidating than it does in person. Mind you, I don’t want to watch plays performed on my laptop screen, when movies do that experience better justice. But magic only works live — or so I thought, until Guimarães found this interactive way to do it virtually. We’re obliged to be involved. Put another way, you must be present for “The Present.”

Illusionists are famous for misdirection, distracting us with one hand while the other performs the trick. Gazing at our screens, we have a clear, well-lit view of Guimarães’ hands at all times. But he still manages to surprise, focusing our attention on the magic while the show’s emotional core — tales of childhood hope and connection that serve to bring the audience together — sneaks up on us. Maybe magic can defeat COVID after all.