The Best Films of Sundance 2019

By Owen Gleiberman

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – Out of all the major festivals, the juries who pick the prizes at Sundance seem to be most, well, independent in their choices. So while “Clemency” and “One Child Nation” took the top awards at the end of 10 days of discoveries, audiences and critics embraced a different group of films entirely.

Billed as one of the year’s most diverse editions ever — with women making up 44% of the directors, and a range of backgrounds on both sides of the camera in every category, not just the world competitions — the 2019 lineup may have been light on stone cold masterpieces, but the overall quality was so high, audiences can expect to see many of these directors and actors directing studio projects, if not Marvel movies, in the near future.

Here, Variety‘s chief critics Peter Debruge and Owen Gleiberman select 13 standouts from this year’s festival.

“After the Wedding”

It’s not often that you encounter remakes at Sundance, a festival where originality and risk may as well be prerequisites for entry. When it came to reinventing the 2006 Danish Oscar nominee, writer-director Bart Freundlich raised the bar for himself by gender-flipping the two lead roles, resulting in a pair of lead performances that give Michelle Williams and Julianne Moore a chance to play an incredible range of emotions. “The Myth of the Fingerprints” director Freundlich, who is married to Moore and hasn’t always been the subtlest when it comes to orchestrating melodrama on screen, follows the original almost scene-for-scene, and yet, by virtue of reinventing the characters as women, he keeps us guessing at every turn. Williams is especially strong as an idealistic American aid worker who’s called back to New York to meet with a possible donor, only to discover the daughter she abandoned decades before — a third great role for relative newcomer Abby Quinn. — Peter Debruge

“”

In Gurinder Chadha’s deliriously romantic rock ‘n’ roll drama, Javed (Viveik Kalra), a Pakistani British teenager living in a drab London suburb in 1987, discovers the music of Bruce Springsteen, and it jolts him alive. Songs like “Dancer in the Dark” and “Prove It All Night” become his fixation, his obsession and identity, his runaway American dream; he just about syncs his heartbeat to that sound, and it lifts him out of the domestic doldrums of life with his immigrant family. (It shows him the promise of something more.) Based on a memoir by Sarfraz Manzoor, this is a coming-of-age tale made with unabashed earnestness, but it’s also a more incandescent ode to the life force of pop music than any movie adapted from the work of Nick Hornby. There are times when it becomes a virtual musical, and it’s occasionally corny as hell, yet irresistible for that reason. “Blinded by the Light” has the courage of its own shameless teen rock-god sincerity. — Owen Gleiberman

“Cold Case Hammarsköjld”

Mads Brügger’s documentary mystery sucks you in like a vortex. It starts off as an inquiry into the 1961 plane-crash death of Dag Hammarskjöld, the secretary-general of the United Nations. Was he murdered? Brügger — bald, twinkly, and a tad officious, like the young Donald Pleasance — is a filmmaker with a prankish reputation but, in this case, a deadly serious agenda. He’s the documentary muckraker as teasing showman, and he plants the seeds of a criminal enigma about race, murder, and the legacy of colonialism that turns out to have shockingly far-reaching implications. “Cold Case Hammarskjöld” doesn’t offer the last word about the issues it raises, but the questions it plants in us are dark enough to reverberate as powerfully as answers. — OG

“David Crosby: Remember My Name”

In A.J. Eaton’s moving and elegiac rock-nostalgia documentary, David Crosby appears before us as an older and wiser hippie troubadour, his signature long hair and frontier mustache now white, his spirit chastened but still keyed to the muse of his holy boomer self. Crosby talks with unapologetic candor about the drugs he did, the women he “didn’t love enough,” the abuse he handed out to his body and soul — and, through it all, the beauty of a long-time-gone rock ‘n’ roll era, when people did what they wanted and the lucky ones (like Crosby) lived to tell the tale. — OG

“The Farewell”

Fans of Awkwafina will get to see another, more dramatic side of the actress in this personal film from writer-director Lulu Wang, who grapples with the Chinese custom of hiding terminal medical diagnoses from elderly relatives. With shoulders hunched and an attitude of sour disapproval etched on her face, Awkwafina plays a version of the filmmaker, who puts her going-nowhere art career on hold to fly back to Changchun, China, where her family has gathered to say their goodbyes to Nai Nai (Shuzhen Zhou) under the pretext of a cousin’s wedding. The Hollywood version of this story would likely share the bemused “bride’s” point of view, offering an outsider’s take on things, but “The Farewell” proves far more sincere as a reflection of an Asian-American immigrant caught between cultures. The result is a triumph in the ongoing fight for representation, inviting audiences to identify with the universal elements in this unusual story of grieving and loss. — PD

“Greener Grass”

From screenwriting winner “Share” (in which a cheerleader’s life is turned upside-down when a drunken video goes viral) to Japanese oddity “We Are Little Zombies” (about a quartet of kids who decide to form a gonzo rock band), a handful of this year’s Sundance breakouts originated as shorts. That also applies to comedy duo Jocelyn DeBoer and Dawn Luebbe’s hilarious satire of a suburb whose well-to-do residents take politeness to an extreme. Expanded from an earlier 15-minute standalone, available online, the pair have fully committed to improv’s “yes, and…” strategy, where one accepts a premise and runs with it, no matter how ridiculous. That way, instead of wearing out its welcome — as so many “Saturday Night Live” sketches do when dragged to feature length — “Greener Grass” manages to sustain its absurdist charms for nearly two hours. Tucked away in Sundance’s Midnight section, this chipper satire has a bright cult future ahead. — PD

“Honey Boy”

Shia LaBeouf takes the daring step of playing his own father in a movie that’s at once a confessional autobiographical psychodrama (LaBeouf seems to be saying to his audience, “See! This is how I got so screwed up!”), a tender and disturbing Oedipal duel, and an exhibitionistic act of Method therapy. The father, James, is a mean, smart, emotionally clueless snaky varmint with greasy long hair and gold-framed spectacles that look like an enlarged version of John Lennon’s. He’s a combat vet and convicted sex offender, the kind of man who stews in his own juice and blames everyone else for his failures. He even blames his 12-year-old son, Otis (the Shia character, played by the remarkable Noah Jupe), a successful child actor who James accompanies to sets, where he’s paid for being his chaperone, though it’s less a parental than parasitical situation: the only job he can get. LaBeouf, who also wrote the script, gives a remarkable performance; he goes to places only a fearless actor working without a net can. “Honey Boy,” staged with grimy small-scale intensity by director Alma Har’el, has a conventional and, at times, slightly lumpy back-and-forth structure, with Lucas Hedges cast as a 22-year-old version of Shia in rehab. Yet it suggests that LaBeouf, as an actor, has only begun to show us what he can do. — OG

“Late Night”

There’s no one quite like Katherine Newbury operating in the world of late-night talk shows today, and the way Emma Thompson plays the idealistic emcee — who’s British, and female, and getting up there in age — one already senses what the relative boys’ club of comedy is missing without a voice like hers on TV. But co-star and screenwriter Mindy Kaling (who started her career with the play “Matt & Ben,” in which lucky dudes Damon and Affleck face a moral dilemma after the script for “Good Will Hunting” literally falls into their laps) doesn’t go easy on Newbury because she’s a woman, challenging other powerful females in the industry who’ve pulled the ladder up after themselves. After being called out for running an all-male writing staff, Newbury picks Kaling as a diversity hire, setting up a smart and satisfying comedy — Aaron Sorkin meets “Love Actually” — that savvily addresses so many of the issues swirling in the zeitgeist today. — PD

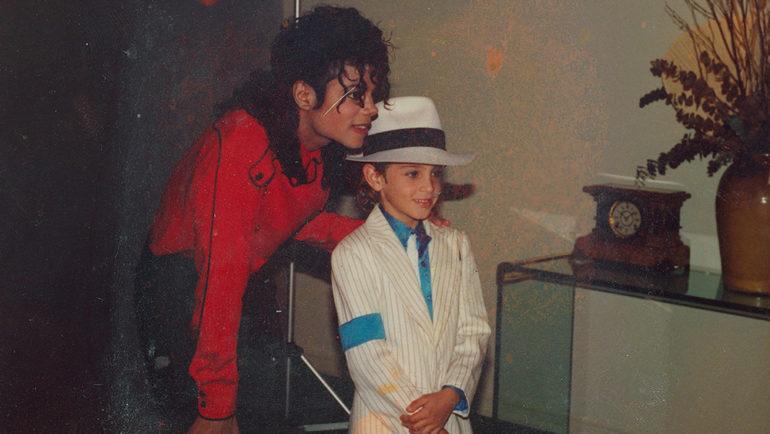

“Leaving Neverland”

In this devastating four-hour, two-part documentary, Wade Robson and James Safechuck testify, with disarming eloquence and self-possession, that Michael Jackson befriended them when they were children and, for years (starting when they were 7 and 11 years old, respectively), sexually abused them. The testimony is overwhelmingly powerful and convincing, and the film suggests that they were far from the only victims. What happened behind closed doors, mostly at Jackson’s Neverland Ranch, was hideous and criminal, but Robson and Safechuck describe the way it happened, and their feelings about it as kids, and that’s part of the film’s revelation. These children felt close to Michael Jackson, and to use their own words, they felt a kind of love for him; they wanted to do whatever it took to please him. The movie captures one of the towering evils of child sexual abuse: that the victims may not experience it, at the time, as “wrong.” “Leaving Neverland” is a disturbing but important document, because what it forces us to confront is that the greatest pop genius since the Beatles was, beneath his talent, a monster. — OG

“Luce”

Adapted from a thought-provoking Lincoln Center play in which a high school teacher (intelligently played by Octavia Spencer in the film) raises the alarm after discovering fireworks in a black student’s locker, this unnerving indie raises fascinating questions about the role of prejudice in tricky situations. The fact that the student is an adopted African immigrant — and former child soldier, reprogrammed through years of therapy— who has turned his life around to become the star of his class complicates the swirl of speculation and response to what could be more than just innocent horseplay. Nigerian-born director Julius Onah offers unique insight into the thorny material, which is told through the eyes of the young man’s supportive, liberal-minded parents (Naomi Watts and Tim Roth), forcing progressive audiences to challenge their assumptions about a character whom Kelvin Harrison Jr. treats as a complicated individual wrestling out from under all the stereotypes projected upon him. — PD

“Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool”

Miles Davis is the one jazz figure of the postwar era who had, and still has, the larger-than-life quality of a pop star. Like Picasso or Dylan, he had a mystique rooted not just in his genius but in his cult of personality, and the mystique only grew the more he mutated — from the glaring-eyed cool cat of the ’50s to the sunken-cheeked fusion hipster of the late ’60s to the raspy funk sci-fi badass of legend. So any documentary that wants to take in Miles Davis has to grapple with each of his dimensions and how they fit together. That’s just what Stanley Nelson’s film does. It’s a tantalizing portrait: rich, probing, mournful, romantic, triumphant, tragic, exhilarating, and blisteringly honest. Nelson is a filmmaker with a sixth sense for how to nudge history into the present, and he catches the spiritual essence of Miles’ story, from the racial despair that spun him into heroin addiction to the drama of his head-turning love affairs to the stunning 3:00 a.m. bebop romanticism of “Kind of Blue” to the six-year break he took from picking up his horn, during which he holed himself up in his townhouse, a burnout trying to claw his way back to freedom. The way the movie presents it, it’s all part of the same story: his need to cast music as a form of possession. — OG

“Official Secrets”

There were a couple of galvanizing post-9/11 political thrillers at Sundance this year. “The Report” (see below) grabbed most of the headlines, but Gavin Hood’s true-life tale of a British intelligence translator, Katherine Gun (Keira Knightley), who learns that the U.S. is trying to gather dirt on U.N. Security Council members to pressure them into supporting the Iraq War is a drama that unfolds with its own elegant urgency. Knightley’s sharply emotional performance never stops surprising us, because she plays Katherine as a feisty ordinary woman who gets introduced, action by action, to her own morality; she turns whistleblower because her instincts won’t let her not. The movie becomes an inside-London-media exposé (who knew that Spellcheck could be so dramatic?), then a skewed courtroom mystery (with Ralph Fiennes as the most cultivated of legal warriors), but it’s finally about how the lies the government tells grow most dangerous when we stop fighting them. — OG

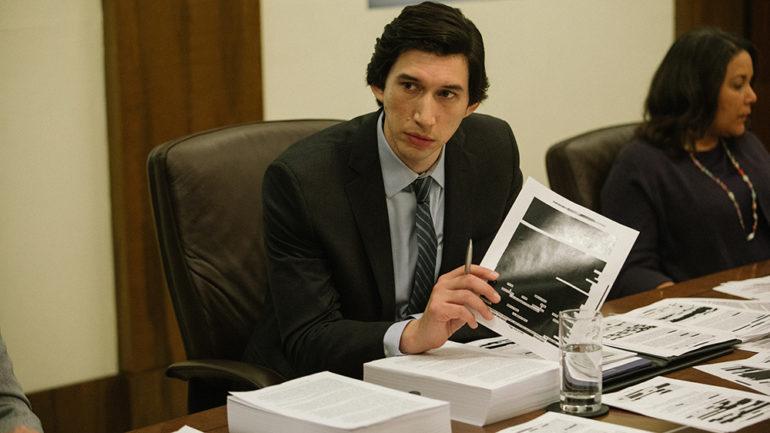

“”

In 2012, the movie “Zero Dark Thirty” helped the CIA sell a cover story that the agency’s so-called “enhanced interrogation tactics” — dubbed “EITs” internally, but deemed “torture” by many on the outside — shortly after “24” had championed Jack Bauer using whatever means necessary to extract information from potential terrorists. That stuff sells popcorn, but movies have a responsibility to challenge the party line on such practices. Writer-director Scott Z. Burns shows the tough stuff in this non-partisan exposé of potential human-rights violations by the U.S. in the wake of Sept. 11, focusing on a Senate select committee investigation ordered by Diane Feinstein (Annette Bening) and conducted by Daniel Jones (Adam Driver) that reveals shortcomings by both the Bush and Obama administrations. It’s a testament to his abilities that he makes the multi-year process feel like a white-knuckle thriller, and a sign of his respect that he never tells us what to think. — PD