Telluride Film Review: ‘They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead’

By Peter Debruge

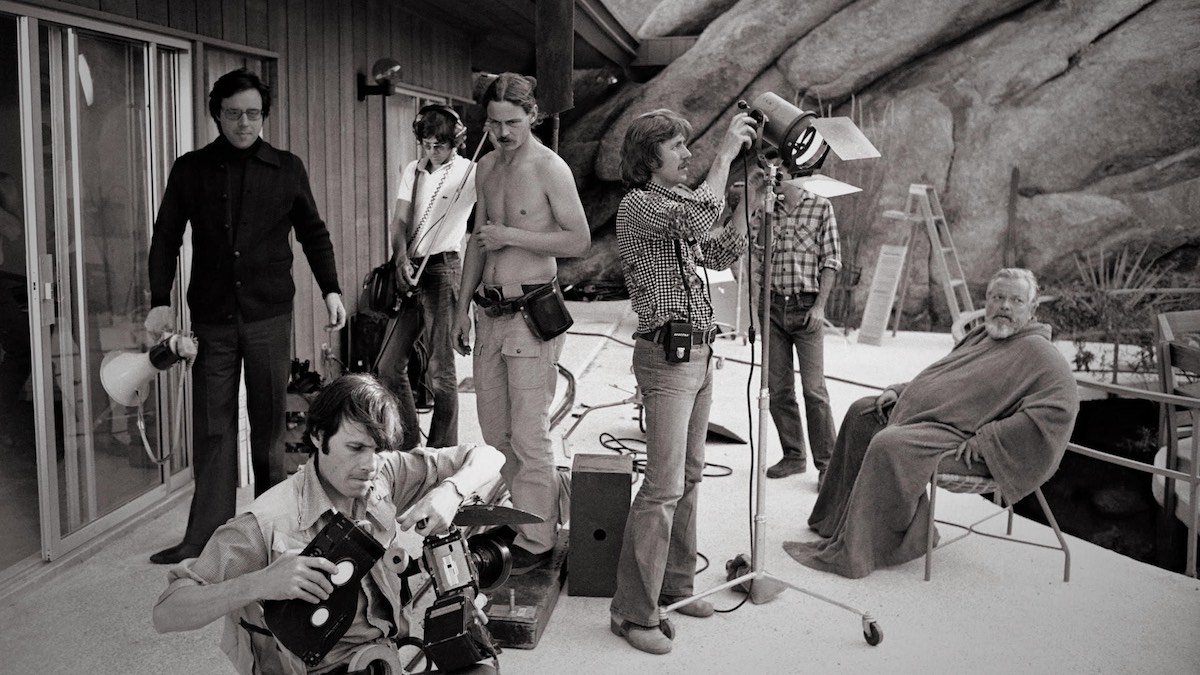

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – It is perhaps the most famous movie never made. Orson Welles’ “” was intended to be his magnum opus, an ambitious meta-movie about a filmmaker’s last night on Earth, intercut with footage of his final project — a parody of an over-stylized 1970s atmospheric art film in the vein of Antonioni, et al. But Welles didn’t finish the movie (he didn’t finish a lot of movies, as it turns out), and now, Netflix has come to the rescue, ponying up to complete this missing piece of the master’s oeuvre — which is not quite the same thing as a “masterpiece,” alas, though that word will get used plenty.

A companion documentary about Welles’ particular obsession with this film, and the final decade or so of his career, “They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead” is not a traditional making-of, nor is it an especially useful reference to how the movie came to be completed. It contains nothing about the restoration and release of Welles’ film (which will find its way to Netflix after special screenings at the Venice and Telluride film festivals). But it says more about the man behind it than any documentary to date, cut together with such a supreme understanding and care for its subject that director Morgan Neville (“20 Feet From Stardom”) seems half-justified in suggesting that his project may as well be the missing film. In other words, if you have the choice of seeing either “The Other Side of the Wind” or “They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead,” you would do well to choose the latter.

Here’s why: “I would like to make a film where it’s like a documentary,” Welles is quoted as saying long before “This Is Spinal Tap” and “The Blair Witch Project” turned mock docs into something of a mainstream genre (but not before “David Holzman’s Diary,” “Medium Cool,” and “Hey, Mom!” first toyed with the idea). As an artist drawn to the avant-garde, Welles was clearly ahead of his time — and possibly, still ahead of ours — imagining a film made entirely of what he called “divine accidents,” the kind of fortuitous gifts for which a director can’t plan (by way of example, Neville points to a scene in “Touch of Evil” in which Welles discovered a pigeon’s egg on the window ledge).

In a departure from his other films, the attention-loving actor turned director chose not to appear in “The Other Side of the Wind,” casting his friend and fellow filmmaker John Huston in the lead role of blowhard director Jake Hannaford — one he insists was not based on himself, even though every detail points to the contrary. Like Welles, the cigar-chomping, alcohol-guzzling Huston has long since passed, but his son Danny appears as one of a vast number of talking heads to offer insights into what Welles must have intended.

Oddly, Neville does not identify the speaking voices in the movie, preferring to use disembodied sound bites, or eccentrically shot black-and-white footage (familiar faces captured from peculiar angles, or else half a head abstractly framed) of family, friends, and others with ties to Welles’ last years, from stalwart DP Gary Graver to sycophantic filmmaker friends Peter Bogdanovich and Henry Jaglom.

These character witnesses — and many others — offer appreciative if not quite adulatory insights. Neville is careful to keep the film from lapsing into hagiography, instead offering a warts-and-all portrait into the most difficult period of Welles’ career — when he “grew immensely fat” and fled to Europe after Hollywood turned its back on him — and the subsequent return, holed up in a private wing of Bogdanovich’s house (Cybill Shepherd’s recollections of this period are especially tragic) — all of which seems to have informed the ever-changing “Wind.” Then-lover Oja Kodar (who features prominently in the film’s notorious backseat sex scene) serves as perhaps the best evidence that he wasn’t entirely miserable in exile.

Here was the creative genius who had given the world “Citizen Kane” — and for whom that film’s success had become a kind of curse, an achievement against which all subsequent work would be judged. And yet, with each new project, he endeavored to push the medium further, often punished for his efforts by having the films wrested away from him and recut by their financiers (as happened with “The Magnificent Ambersons” and “Touch of Evil”). In other cases — “The Deep,” “The Merchant of Venice,” and “The Dreamers” — the films were never completed, leading some to wonder whether Welles deliberately self-sabotaged, drawing projects out over many years to prolong the sheer thrill of their creation, as if reluctant to disband the troupe with whom he took such pleasure in collaborating.

Neville manages to raise at least a dozen equally insightful theories about Welles’ working method, but winds up with sources constantly contradicting one another. “It’s almost true,” Bogdanovich says at one point (he’s frequently the most eloquent interviewee but easily the most compromised, busy constructing his own legend in the process). Another calls the myth that Welles abandoned projects “bullshit,” explaining, “He wanted to finish them correctly,” which sounds like a plausible interpretation of his perfectionism.

In any case, it’s a tricksy film, taking cues (and quite a few clips) from Welles’ 1973 oddity “F for Fake” in its wily structure. As if it weren’t a daunting enough assembly as is, Neville adds a curiously anachronistic framing device, in which a waxy-looking Alan Cumming appears like the host of a vintage television program, supplying dry narration over black-and-white footage of film being threaded through a projector or spliced on a flatbed editor.

It’s a corny device compared with the wonderfully sophisticated way editors Aaron Wickenden and Jason Zeldes work with archival footage, constructing entire scenes (a phone call, a test screening) from clips of “Wind” and Welles’ other on-camera appearances, including an odd bit on “The ABC Comedy Hour” (aka “The Kopykats”), where he met impressionist Rich Little (whom he would later cast, then replace, in a key “Wind” role).

Judging by the generous amount of “Wind” included in Neville’s doc, the movie seems likely to live up to Welles’ promise that “You either hate it or loathe it,” being an unhinged and constantly evolving industry parody, à la Dennis Hopper’s “The Last Movie” (incidentally, Hopper was one of the many self-skewering participants in Welles’ experimental project). After nearly half a century, audiences can finally witness Welles’ folly. Watch this first, and then weigh Neville’s playful assertion that his meta-movie may in fact be truer to the master’s intentions. It’s a bold claim, all but unprecedented in behind-the-scenes docs: Could “They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead” be the real “The Other Side of the Wind”?