Mud, Music and Community: Memories of the Original Woodstock (Guest Column)

By Gary Wagmeister

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – When news broke that Woodstock would be having a 50th anniversary festival in 2019, I immediately received an inquisitive call seeking more information — from my 67-year-old father. “What’s this I hear about another ?,” he asked with a little excitement but more skeptical curiosity, which turned out to be a fair reaction, as the anniversary festival collapsed and was cancelled last month.

He was curious not because he’s a pop-culture aficionado (my family is very proud of my work as an entertainment journalist at Variety, but they’re rarely seeking more information on the Hollywood headlines of the day) but because he’d attended the original Woodstock festival in 1969, when he was just 17 years old.

All of my life, my dad shared stories of his time working as a busboy in the Catskills and the unforgettable weekend he happened to mosey on down to Woodstock. And as someone who’d spent an entire editorial assistant-level paycheck to attend Coachella with my friends, I couldn’t believe that he’d simply walked into Woodstock without a ticket — let alone a giant festival where the music went on until late the following morning.

What was it like? We’ll let cub reporter Gary Wagmeister take it from here. — Elizabeth Wagmeister

In the summer of 1969, I was 17 years old and had just graduated from high school. I was working as a busboy at the Raleigh Hotel in the Catskill Mountains in upstate New York. At the time, the Catskills were a popular resort area, with upwards of 200 small hotels and bungalow colonies catering to family vacation for people, mostly from New York City. Most of the waiters and busboys that I worked with were students who worked at the hotels as summer jobs. I remember how we all marveled and tried to crowd around televisions on July 20 when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the moon, and the celebrations that followed. Though the Raleigh was located just 10 miles from the Woodstock festival site, when the weekend of Woodstock approached, I knew little about the festival and had no plans to attend. I was working to save money, as I was about to attend college in September.

But my interest, along with that of three of my friends, was piqued the day before the festival started, as we heard the news and TV reports about the traffic jams and the mass of people trying to get to Woodstock. “We have to go,” we said. “This is a once in a lifetime event.” But we had to serve three meals a day to the hotel guests, from 8 a.m. until 9 p.m. One of my friends — the “old” guy of the group, at 20 years old — came up with a solution. He had worked in the Catskills for three summers and knew the back roads through the woods, so he suggested we go after serving dinner each night and try to get to the festival site. If we couldn’t get close enough, we’d turn back. But if we did, the groups would be performing until at least 2 a.m., so we could go back to the Raleigh and catch a few hours of sleep before it was time to serve breakfast.

It was pouring rain on Friday night, so we decided to wait until Saturday. But there was a problem: The festival site, which was now filled with approximately half a million people, was a pile of mud. We’d planned to sleep between lunch and dinner, but the local hotel owners had heard about food shortages on the site and agreed to supply meals to the festival, so all of us waiters and busboys were tasked with making thousands of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches to be helicoptered to the festival site. I think all of us at the Raleigh prepared 2,000 sandwiches; I later heard that the hotels and local restaurants flew in over 100,000 sandwiches to Woodstock on Saturday and Sunday. I also later heard from my friend’s father, who had the cigarette concession at the festival, that the 30,000 cartons of cigarettes he’d stocked were completely sold out 36 hours after the festival started.

By then we’d heard that the crowd had become so large that the festival organizers had stopped bothering to collect tickets — that solved one of our problems — but we still had to contend with the mud. So we stole a dozen tablecloths from the hotel linen supply room to sit on, and we also rolled a few joints (which we didn’t get from the hotel supply room) to take with us.

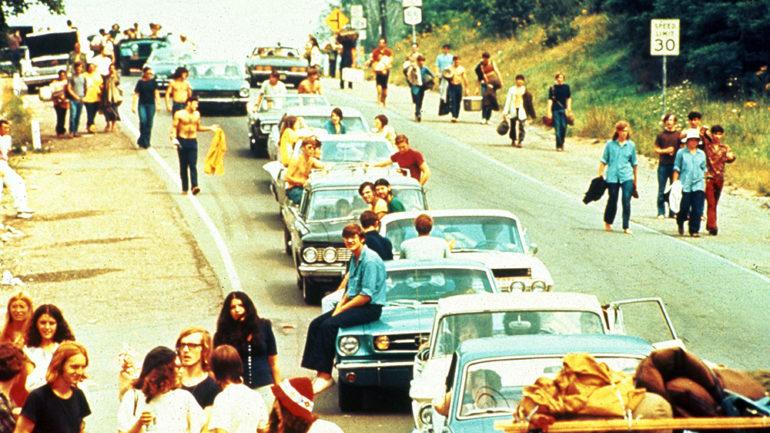

After serving dinner, at around 10 p.m., the four of us piled into my friend’s 1963 Chevy Impala with our provisions. We got about a half mile from the site and walked the rest of the way. It was a crazy scene: Other cars were trying to get closer but were moving at approximately one mile per hour; people were hitching rides and sitting on cars’ roofs or trunks — many had 10 people inside and outside.

Of course, the rain and the chaos caused serious delays with the performances, which worked in our favor: When we finally got to the festival site at around 11:30 p.m. the Grateful Dead, who were scheduled to play hours earlier, were onstage.

We wanted to get closer to the stage, but it was at the bottom of an amphitheater-like hill, and the night was so dark we could hardly see the people sitting on the ground; the only light was the constant tiny flashes from people lighting their joints and cigarettes. As we moved forward, it was impossible not to step on people — most were actually cool about it (or too stoned to notice), but one guy seemed angry, so I handed him a joint. “Groovy!,” he said. “You can step on me again if you want to give me another joint.” We finally found a small open area about 50 yards from the stage, unfurled our tablecloths over the mud and sat down to enjoy the music. Within half an hour all of our supplies were gone, but that was Woodstock: There was a sense of togetherness that is my most vivid memory of the festival.

The Grateful Dead were followed by Creedence Clearwater Revival, Janis Joplin, Sly and the Family Stone, The Who and, in the early morning, the Jefferson Airplane. I had not previously been a big Janis Joplin fan, but she was absolutely fantastic and exhibited raw emotion and energy, especially on “Piece of My Heart” and “Ball and Chain.” Sly and the Family Stone tore the place down, getting thousands of people onto their feet at 4 a.m. The Who were spectacular and performed most of their then-new rock opera “Tommy.” At one point during their set, activist Abbie Hoffman grabbed a microphone and started ranting about politics — as the crowd started booing, The Who’s Pete Townsend pushed him offstage, to large cheers from the audience. As the group finished off “Tommy” with its closing number, “See Me, Feel Me,” the sun began to rise. For the first time, I was able to see the enormity of the crowd of 500,000 people — I’ll never forget it.

By that time our hotel duties were calling, so we missed the Jefferson Airplane in order to serve breakfast at the hotel. On this day, we managed to catch a couple of hours’ sleep in the afternoon, and after serving dinner we headed back to the festival with a fresh supply of joints and tablecloths — and, this time, flashlights. We arrived at midnight and saw great performances by Johnny Winter, Blood Sweat & Tears, Crosby Stills, Nash & Young, Butterfield Blues Band, Sha Na Na and Jimi Hendrix. A large percentage of the audience had left before Hendrix’s set — it was Monday morning, after all — but we’d taken the day off. Unfortunately, the delays had caught up with Hendrix (he went on eight hours after his scheduled set time of midnight), and it wasn’t one of his best performances — but, of course, it included his historic version of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

These are great memories, but until this 50 th anniversary, I actually hadn’t thought much about Woodstock. Which is surprising: It was a once in a lifetime experience. The music was great and the local community turned out to be very supportive, but again, the most memorable element was the sense of togetherness in the crowd. Over the past 50 years, most of the people I have met who were there said they feel the same way. At the time, many people didn’t care much for hippies, but this audience pulled together as a temporary community — no one cared about your politics or the color of your skin. The closest thing to violence that I witnessed was the guy who got annoyed when I accidentally stepped on him (and asked me to do it again in exchange for another joint). I haven’t been to a modern-day music festival, but hopefully the festivities and media attention around this Woodstock anniversary will be an inspiration to the organizers and the audiences: It’s not about money or being seen, but about community.