Martin Scorsese Recalls Parents’ ‘Stunned’ Reaction to ‘Mean Streets’

By Alex Barasch

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – Since its inception half a century ago, Film at Lincoln Center has championed outsiders, both geographically and artistically. It’s stood up to the Catholic Church, the U.S. Customs Office, and its own donors to screen the work it believed in — and jump-started the careers of internationally renowned actors and directors in the process. At its 50th anniversary gala on Monday night, an all-star cast ranging from Almodóvar to Scorsese looked back on that history and paid personal tribute to the organization that welcomed them when no one else would.

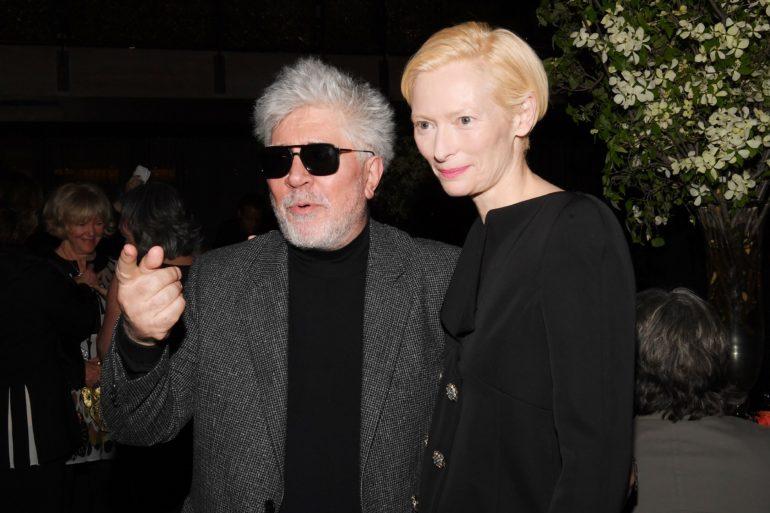

For Pedro Almodóvar, the 1985 selection of “What Have I Done to Deserve This?” as part of New Directors/New Films changed everything. “My birth happened at that moment,” he told Variety before the ceremony. “It was the first time that one of my movies could be seen for the American audience, so I got the feeling that everything depended on this.”

Even then, promoting art from around the world was an important part of the institution’s identity. “The first time I went to the offices of John Koch, I was so impressed with what’s on the walls: portraits of European directors like Truffaut and Fellini and Fassbinder,” Almodóvar said. “I was almost in shock — like, ‘Oh, my god, I cannot believe they are inviting me to be part of this.’”

Critics weren’t always as kind (one described his New York Film Festival debut as “often tasteless but never dull,” which Almodóvar says he “adopted as the best possible definition of my cinema and of myself”), nor were other programmers. The now-iconic “Woman on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown” was first rejected by Cannes because it was a comedy — but when he brought the film to Lincoln Center in 1988, “Everyone embraced me like family.”

“Hereditary” director Ari Aster’s life was also changed by NYFF’s willingness to take a chance on his work. “‘The Strange Thing about the Johnsons’ [Aster’s first short] was rejected by so many festivals, and the New York Film Festival was the place that really embraced it,” he told Variety. (He’d had a one-sided love affair with Lincoln Center long before that: he first subscribed to Film Comment when he was 12 years old.) “At that point in my life, that was the biggest thing. And when you get to see films in the Alice Tully — there’s not a screen like that in the world.”

Dee Rees believes such showcases are the best way to find great new artists. “If you catch a filmmaker’s short films, that’s the point to eye new talent, even before the features,” she told Variety, citing Haley Anderson’s “If There Is Light” as the latest to catch her attention.

For Rees, whose first feature, “Pariah,” was a New Directors/New Films selection in 2011, Film at Lincoln Center has been a democratizing force for an industry that urgently needs it. During the ceremony, she spoke about the history of discriminatory distribution practices that persist to this day, alienating black audiences and “fueling the falsehood that black films don’t sell.” By contrast, she said, Film at Lincoln Center “shows us clearly the importance of unobstructed vision and multiple perspectives” — including that of a “small, independent film about a lesbian teenager in Brooklyn.”

“I remember being amazed that this Upper West Side crowd would watch ‘Pariah,’” Rees told Variety. “It made me realize the film was truly universal, because the audience responded just as strongly as they had at other places.”

The validation she felt that night mirrors the experience of another young filmmaker decades earlier: Martin Scorsese. When “Mean Streets” was screened at NYFF in 1973, it was “the defining moment” for the 31-year-old director — though his parents’ feelings about the premiere were more mixed. After the screening, “My mother was stunned, and my father was kind of ashen,” Scorsese recalled, laughing. (Asked what she thought of her son’s film, Catherine Scorsese said only, “I just want you to know, we never use that word in the house!”)

Tilda Swinton also found herself at NYFF at the beginning of her career, traveling to New York with “The Last of England” in 1987. “The welcome we received here was something remarkable to us,” she said, calling the Center “a place of real safety, comfort, and joy.” More than thirty years after that fateful screening, the Oscar winner still considers it a place deserving of reverence: “Lincoln Center is our temple, and all of us count ourselves lucky to sweep her floors and light her candles.”

Other speakers evidently felt the same way — and Almodóvar ended his speech with a prediction befitting the institution’s legacy in New York and beyond. “As long as Film at Lincoln Center exists, cinema will live on,” he said. “If you’ve survived five decades, it means you’re eternal, honey!”