London Theater Review: ‘Antony and Cleopatra’ With Ralph Fiennes

By Matt Trueman

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – The personal is political. Politics is personal. Few plays understand either statement as fully as “Antony and Cleopatra.” In showing us the private lives of politicians — the great loves of great warmongers — Shakespeare stresses that the two can never be disentangled. A lovers’ tiff can launch a thousand ships; a red rose can trigger a nuclear strike. With Ralph Fiennes and Sophie Okonedo as its power couple, Simon Godwin’s clear-sighted production at the National Theatre turns that truth on our tempestuous times. It’s a warning that world leaders are only too human; that passions and politics are best kept apart.

Godwin’s off to Theatre in D.C .next year and, like Nicholas Hytner, he can stitch Shakespeare into the fabric of our world seamlessly. His modern-dress Rome is recognizable from the word go and its elites, like our own, are well out of the fray. Godwin shows us the super-rich at work and at play.

So while Tunji Kasim’s serious Caesar is briefed about populist uprisings and pirate hoards in a marble chamber dotted with indigenous art, Antony and Cleopatra are seen swanning around an Egyptian swimming pool, stretched out on sun loungers, fondling while Rome burns. Antony’s expected back at home, but Fiennes, who has the air of an old hippy on holiday, his swirled shirt open on prayer beads and a faded scarab tattoo, is entirely wrapped up in Okonedo’s glamourpuss Cleopatra. No matter how many suited servants bring “news from Rome” into this languid, luxury resort, it hardly cuts through. He sips from his beer as he plots military maneuvers.

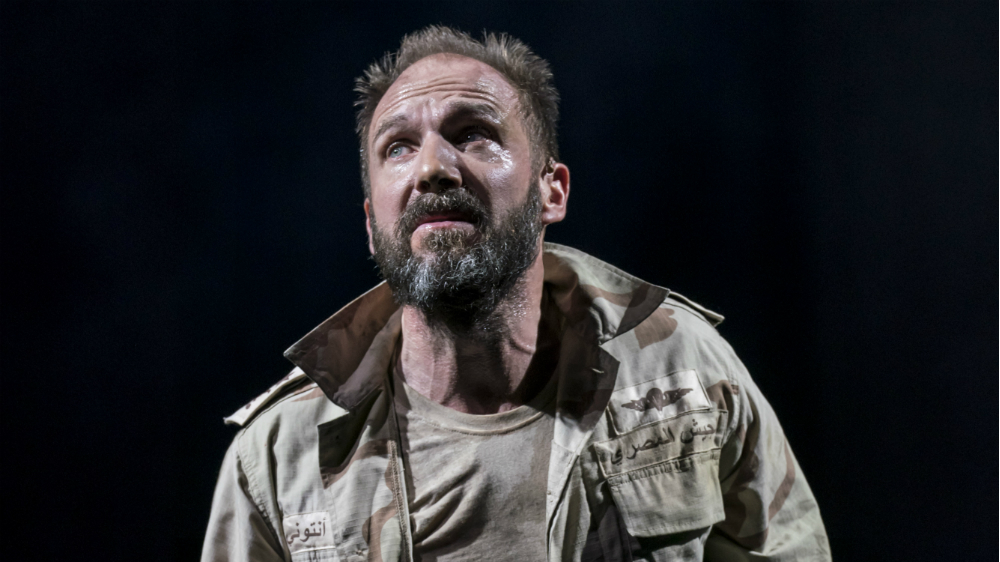

Godwin makes clear that individual relationships and rivalries ripple out across populations at large. Fiennes gives us an ultra-alpha Antony clearly feeling his age who squares up to Caesar and leads troops into misguided battles just to prove his masculinity and impress his impetuous mistress. He crams himself into muscular body armor with vain pomp as Cleopatra marvels on. Okonedo, meanwhile, makes her moods as changeable as her outfits; a diva who knows the power of her allure. When she gets wind of Antony’s second marriage, not only does she nearly drown Fisaya Akinado’s messenger, she threatens to “unpeople Egypt” as a whole. Both are hotheads, both are heavy drinkers and their rash decisions have huge ramifications.

If Antony and Cleopatra govern with their groins, Godwin surrounds them with level-headed advisors. For all he enjoys the perks of Antony’s slipstream, Tim McMullan’s sage Enobarbus calculates the perfect moment to step out of it, and Katy Stephens’ Agrippa counsels Caesar with a cutthroat detachment. They’re offset by Gloria Obianyo’s demure Charmian, who steers Cleopatra with a soft touch. The play’s quieter characters are all but bulldozed, and it’s a measure of the strength of Godwin’s vast cast that so many of them register, even in near silence: Akinado’s Eros, too civil a servant; Nicholas Le Provost’s mumuring military man Lepidus and, best of all, Hannah Morrish’s tongue-tied Octavia, meek to the point of muteness.

However, it all reads better than it plays, and Godwin’s tendency to keep texts almost fully intact, protecting from cuts, bogs it down. His staging falls foul of the play’s second half where it might, so easily, have made a virtue of it. It’s not so much the tip into warfare, staged with flashbangs and Fiennes going full Rambo, that feels over the top, it’s that Godwin never unlocks a language to make something impactful of the play’s plague of suicides. Instead, his staging unravels in a procession of burst bloodbags and corpses, each death a little less impressive than the last, that never keys into the senseless poetry of it all or the headlessness of self-destruction. As swathes of people succumb to their swords or to snakes, personal tragedies pile up into something horribly political.