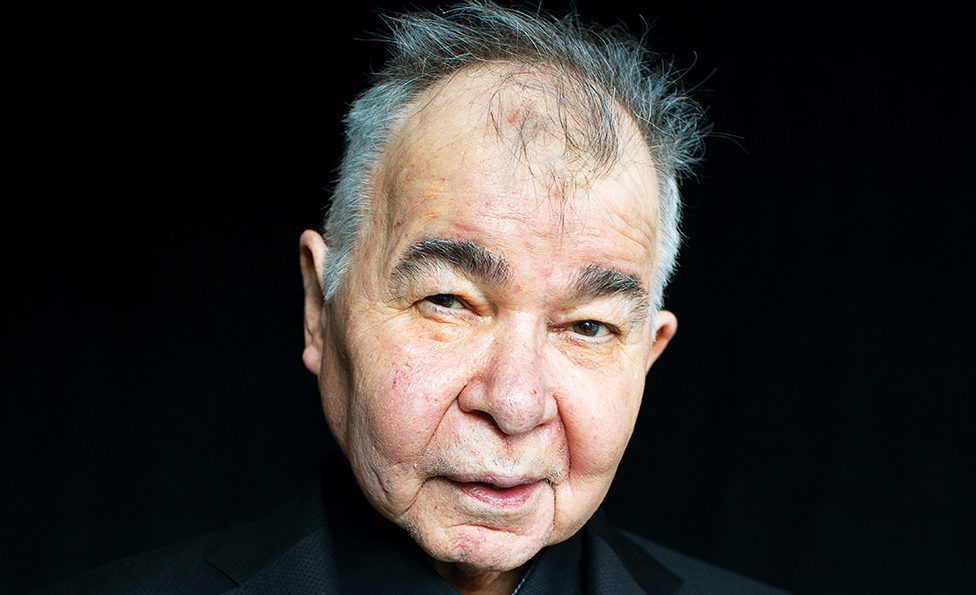

John Prine in Memoriam: A Friend Celebrates the Playful Heart of America’s Great Campfire Poet

By Holly Gleason

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – John Prine had a night off before playing Miami’s historic Gusman Theater. After dinner, he wanted to do something, and thought a movie might be good. I told him there was a small mom ’n’ pop filmhouse called the Surf just up the way showing Rodney Dangerfield’s “Back to School.” Having just started seriously dating Dan Einstein, his co-manager, I wanted him to have a nice night out. The Maywood, Illinois son of a ward heeler thought he could use a laugh. So, why not?

Standing in the lobby with his popcorn, waiting to get in, a guy walked up, clearly gobsmacked. “John Prine?”

“Yup,” he chuckled, already having fun.

“Oh, my God, I’m gonna see you tomorrow night.”

“And you’re seeing me right now,” he volleyed, clearly delighted.

“Oh my God, what are you doing here?”

“Seeing the movie, just like you.”

Just like you. Just. Like. You. If there was ever a truth that was larger than the kindness that infused his writing, the clear eye for social betrayal and the ability to find metaphors and moments no one else sees, the first of the “new Bob Dylans” really was just like us.

The former postman, who dreamed up songs daydreaming along his route, tapped into the human condition with a pathos often leavened with yearning. At 11, when I was far too young to understand marital ennui, Bonnie Raitt’s “Angel from Montgomery” bled out all over the floor of my pink bedroom. I was supposed to be asleep, had Cleveland’s WMMS on low, and that question, “How the hell can I person go to work in the morning / Come home in the evening and have nothing to say?,” burned a hole in me.

An only child in a family that would generously be deemed “high impact,” I suddenly knew the brutal truth: the space ship I’d fallen out of was not coming back for me. I was alone with these people — but I was also not alone. Because this song existed, I had the comfort of knowing “to believe in this living is a hard way to go,” and to ask, “Just give me one thing that I can hold on to…”

How many school books were scarred with the lyrics from “Angel”? I can’t tell you. But the year I sent John my seventh grade French book as a Christmas gift, he called, laughing, saying, “If I’d known you were a stalker…”

He did that to people: saw and sang the essential, what Antoine St-Exupery wrote in “The Little Prince” “can only be seen with the heart.” Precious-sounding, but not even close. He was a naughty boy with a laugh like gravel, who stayed up late, smoked cigarettes and had friends over for candlelight tabletop bowling.

Katie Cook, aka the Katie Couric of CMT, sidled up to me at a shoot once and said, “You know, I thought John was a bartender for the longest time. I used to wake up to go to school, and he’d be asleep on our couch. And then one day when I was in high school, I walked into Tower Records, and there were all John’s records on an endcap. I almost fell over! Here he’s this rock star American songwriter, and I didn’t know.”

Her father, Roger Cook — the natty British songwriter who’d moved to Nashville and written hits for Don Williams and Crystal Gayle, not to mention “Long Cool Woman in a Black Dress” and “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing” — was part of Prine’s extended running posse. It also included Jim Rooney and “Cowboy Jack” Clement, the Sun Records alum who’d written “Ballad of a Teenage Queen” and “Guess Things Happen That Way.” Old-school creative types, always up to music and whatever trouble they could get into.

At the dinner table at the Stephen F. Austin Hotel in Austin the night before the second Farm Aid, somehow Cook decided to show everyone how he could put a champagne cork up his nose. Only then he couldn’t extract it. Once the knee-slapping stopped, Prine’s arm’s encircled his buddy, someone else anchored John and a third person reached across the table for leverage. It took a few good pulls, but finally there was a pop! Once the guy with the dark hair falling across his eyes knew his friend was okay, it called for a round to toast a story to tell.

And that was John: have some fun, and if you got a little sideways, fix it and get a story to tell.

So many sights to remember … like an Aqua Velva bottle sticking out of a cowboy boot — the perfect punctuation for a working Joe having finished a full day’s work. Standing half a flight above, I smiled: he looked like a perfect mix of Charles Bronson, Sam Shepard and Stanley Kowalski.

John Prine was the poet of the working man, a guy who got bothered by the ways we betray the weak and the vulnerable. The singer-songwriter who core-sampled the human condition as a post-folkie voice went on to spend the next decade and a half sharing the stories of the soon-to-be-dead junkie Vietnam vet of “Sam Stone,” the misfit lovers who never connect in “Donald & Lydia,” the forgotten old people of “Hello in There,” the teen suicide with a secret in “Six O’Clock News” and the middle-aged woman passed over in “The Oldest Baby in the World.”

If you didn’t know the guy chewing the gum with the flat Midwestern vowels and the deep set eyes was the original “new Bob Dylan,” he could be anyone. But in many ways, he was everyone.

As the new(ish) girlfriend of the young co-manager, brusquely dismissed from the Palm Beach Post, I was feeling wrongly accused and mortally wounded. Always a big stick-up for the other guy, John — the cupid who pushed us together from L.A. and West Palm Beach — decided a trip to Europe was just the thing. Folk festivals and theaters, vintage Daimlers to haul us to Cambridge, flights from Heathrow to Belgium, high teas, broken strings. A whirlwind trip through art museums, the countryside, cathedrals, Harrods.

The road was not new to me. Having written the bio for his album “German Afternoons,” I’d joined his touring party, including award-winning “Today Show” producer Mike Leonard, at Wolf Trap for a sold-out show on a night so hot and humid, you could literally wring the air out. I watched the fans press into the stage and yelped, “They’re going to hurt him,” only to be told by tour manager Garry Fish, “Hurt him? They love him. Watch.”

I was deemed tourworthy, except I couldn’t stop crying. And John, being a friend to all wounded souls, decided to try to cheer me up. Standing in baggage claim in Belgium as Fish gathered the gear and the luggage, John came up and offered chocolate, then flowers, then a stewardess Barbie. Tears, tears and more tears.

“Aw, heck, Holly,” he finally said, “if they’re stupid enough to set you up, then knock you down, so what? You’re gonna be a big deal music writer, and they’re gonna be in West Palm Beach.” That broke me. Here was John Prine, the guy who punched a hole in my childhood and let some light and air in, doing it again.

John had that way of knowing what you need, when you need it. Yes, he’d write songs that skewered self-interested politicians (“Caravan of Fools,” “Some Humans Ain’t Human”), lambasted marketing bombast and marital discord (“Quit Hollerin’ at Me,” “Spanish Pipedream”), poked at jingoistic patriotism and empty self-improvement (“Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You Into Heaven Anymore,” “Dear Abby”) and delved into fame’s life-sucking reality (“Picture Show,” with a video featuring Tom Petty).

But he also traded in a romantic vein swathed in tenderness. The yearning “Storm Windows” and “One Red Rose” were sigh-inducing moments when he’d play them — one a paean to being trapped in a Midwestern winter where the time slows and you’re left to your thoughts, while the other cradles a moment of sheer bliss like the little matchgirl with that flame holding a vision.

And there was the irony. Few things were as funny as “Let’s Talk Dirty in Hawaiian” with the herky-jerky word play and the climax of “Would you.., like a… lei?! HEY!” Hey! Like “Illegal Smile,” it would bring crowds at the Wilshire Theater, Carnegie Hall, Wolf Trap, the Ryman, Red Rocks and around the world into pure singalong rapture. More than giving as good as he got, he tapped into that place where everyone just wants to sit around a big ole campfire and get their innocence back.

In times like these, innocence is more precious than rubies. John understood that, an he understood the power of Tennessee charities like Thistle Farms (which helps get prostitutes off the streets and into job skills), Room at the Inn and the Nashville Mission to help the folks who fall through the cracks.

If he had a thing for long, black, tricked-out Cadillacs, vintage or otherwise, he also knew meatloaf day at every meat ’n’ three in Nashville. When he’d go through the door, it was like a family reunion; not only did they know his name, he knew all theirs.

George Dassinger, a publicist friend I’d hooked up with John’s Oh Boy label for “The Missing Years,” tells the life-lesson story of trying to warn John about New York City panhandlers. Prine looked him in the eye and said, “George, what’s a dollar worth today? Fifty cents. Give the guy a buck.”

“Are you still going to church?” he asked me, leaning a little closer after slaying tens of thousands of people at San Francisco’s free Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival in the Golden Gate Park. He’d retreated to a cabana-style tent that served as the headliner’s dressing room, and he was serious.

“Oh, God,” I cringed. “He’s going to give me his testimony. He’s lived in Nashville too long…” Summoning all my courage, I stammered, “Well, I’m Catholic….”

“I know,” he returned, a big grin on his face.

I wondered where this was going, but I‘ve never dodged the found uncle who’d practically raised me. Sighing, I explained, “It’s a hard thing to find a good Catholic church in the South.”

“That’s what I thought,” he offered, happy to help. “Well, Fiona and Maura O’Connell found this place called St. Patrick’s, down on Second. Built for the Irish when they were migrating West, it was the first Catholic church in Nashville – and I bet you’d like it.”

Just when you’re sure you know, John Prine takes a hard left and leaves you speechless. Fiona Whelan Prine, his Irish bride who’d run U2’s Windmill Studios in Dublin, was a fierce community activist, a mother of three and always a woman of great faith. The church was small, wooden, maybe held 200 people freight-packed. But like a mustard seed, the narrow church was about believing and God’s grace.

Classic Prine move. Know what you need even when you don’t. Working from kindness of the heart, not anything to gain. And always reminding you that no matter how small or invisible you thought you were, he saw you.

Of course he did. He saw everything. “There’s a hole in Daddy’s arm where all the money goes…” from “Sam Stone.” “Old people just get lonely…” in “Hello in There.” And there were the “Unwed Fathers” who “can’t be bothered, they run like water through a mountain stream.”

It’s funny how now John Prine is an American icon. After a series of deals with the majors, he paved the DIY indie label business with Oh Boy, after his best friend Steve Goodman founded Red Pajamas because his leukemia kept major labels from offering the guy who wrote “The City of New Orleans,” “Go, Cubs, Go,” “My Old Man” and “You Never Even Called Me By My Name” a deal.

John felt like the labels took all the money, had all the power. He figured less money, more power would mean a better outcome for people who loved his music. Initially selling mostly via mail order, his co-managers Dan Einstein and Al Bunetta built the label; Prine worked the road.

It worked pretty well. “German Afternoons” would lose the inaugural Contemporary Folk Grammy to “A Tribute to Steve Goodman,” an all-star homage concert collecting the Chicago folk scene both men had emerged from. At the 1987 Grammys pre-telecast, Prine was the happiest loser you’d ever seen. If it wasn’t gonna be him, it was his best friend.

“I put my hand on a rock, and said, ‘I’m a record company’,” Prine tease-answered in an interview decades ago when I asked how he did it. But the truth is that the independent spirit liked the idea of owning his music, having control of how it was presented, marketed, sold. He turned down millions of dollars — back when that was a lot of money — to protect the thing that really mattered: his music.

And he maintained that for over 35 years. Even signed the man who got him his first record deal, Kris Kristofferson, as well as Todd Snider, Dan Reader, the Bis*Quits (with Nashville’s Grimey’s and Basement owner, Michael Grimes), author Tommy Womack and sometime Coral Reefer Will Kimbrough, just because he liked their music.

After his first cancer bout, he made the Grammy-nominated “In Spite of Ourselves,” a collection of vintage country classics with Melba Montgomery, Connie Smith, Patty Loveless, Lucinda Williams and Trisha Yearwood. Why? “Because I like singing with girls.”

Longtime friend Iris DeMent not only dueted on the George Jones/Tammy Wynette classic “We’re Not the Jet Set,” she provided the girl’s perspective on the album’s only original, the title song, which he’d written for Billy Bob Thornton’s “Daddy and Them.” A demi-roots classic, it boasts DeMent’s wry scold, “I caught him once, he was sniffing my undies,” making it a de rigueur duet.

It’s unfathomable someone with so much love, so much life is gone. A PEN Award winner, a Songwriter Hall of Fame inductee, a Grammy Lifetime Achievement winner, on top of 11 Grammy nominations and two wins, the first songwriter to read in the Library of Congress — these are the tip of the accolades. But if you asked him, what made him happiest was falling in love with an Irish girl, having a family, living the life.

Fiona was a true blue sweetheart who made him laugh. He told me once when they first started dating, “I looked out the window, and saw her hanging my shirts on the line, and I just fell in love.” Love, real, deep, true love, the kind we all seek.

John took to her family across the sea with his great big ole candy heart. When the cancer came the first time, he had three black-headed boys and his Irish bride. Yes, he had the best people at MD Anderson, but he had a secret weapon to go with his fierce desire to not leave his family.

“My mother-in-law would be baking me these apple pies,” he marveled. “And man, I’d be going through the treatments, and I couldn’t wait to get home. I could smell them in my mind all the way from Texas.”

A homemade apple pie. The yearly treks to Paradise, Kentucky for the Everly Jam shows to raise money for Muhlenberg County. An all-day line-up of all kinds of artists, headlined by Don and Phil Everly, it was the epitome of sweetness in the place where his grandparents lived and Prine journeyed as a child with his brothers. Memorialized in “Paradise,” where he juxtaposed little boys who’d “shoot with our pistols, but empty pop bottles was all we would kill” with the strip-mining ravages of “Mr. Peabody’s coal train that done hauled it away.”

Family mattered. Literal and extended.

It’s why when Bunetta died, he turned in on those Midwestern roots and did what working class kids from the Midwest do: made it a family business to take care of his own. He installed son Jody Whelen as operations manager and his wife Fiona as his actual manager, two who recognized Prine’s love of true creatives and started building bridges to the rising icons of alternative and Americana music.

Jim James, Jason Isbell, Kacey Musgraves, Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon, Sturgill Simpson, Margo Price, Dan Auerbach, Amanda Shires, Brandy Clark and Brandi Carlile were all thrilled to spend time with the guy whose music defined what was possible and set a bar for excellence married to humanity. John loved the youth and creative energy. It was new worlds, new views, a whole lot of music.

So much fun that Fiona knew she had to do something to get him back to work on new songs. She booked him into a hotel downtown, told him to pack his notebooks and said “don’t come home till you write a record.” What emerged was the heartbreakingly perfect “The Tree of Forgiveness.”

The man who’d worked with Arif Mardin, Sam Phillips, Jim Rooney, Howie Epstein and Cowboy Jack teamed with Dave Cobb and drew on good friends Pat McLaughlin, Keith Sykes, Cook, Auerbach and even a forgotten Phil Spector fragment for the material. Joyful, loose and freewheeling, and nonsensical in places, it was quintessential Prine.

“When you got hell to pay, put it on lay-away,” he crows on “Egg & Daughter Nite, Lincoln, Nebraska, 1967 (Crazy Bone)” over a barrelhouse neo-Dixieland romp. With a wink, he draws a picture of the ne’er-do-wells, waiting on the girls. “Well, you’re probably standin’ there / With your slicked-back Brylcreemed hair / Your Luckys and your daddy’s fine-toothed comb…”

Sketch a moment, a prototype, an intention. Just as adroitly, he invites the lost, scared and broken in with the softly mournful “Come on home, come on home / No, you don’t have to be alone / Just come on home” refrain in “Summer’s End,” its video ultimately dedicated to former Nashville mayor Megan Barry’s son Max, who died from an accidental overdose.

Bob Dylan would cross a packed Dan Tana’s to say hello and chat. Bruce Springsteen would use Prine’s passing from COVID-19 as a way to focus outrage and awareness on his SiriusXM radio show. The President of Ireland would issue an international proclamation upon hearing of Prine’s death.

But, to me, John will always be the guy in striped pajamas, hair askew in the lostest hours of one specific Holy Saturday. Having flown into Memphis from L.A., I’d run into him watching the ducks’ afternoon march in the bar of the Peabody Hotel, where Prine had taken over the bridal suite for a days-long card game. The bars had closed, my friends and I were hungry, and I had a brilliant idea — because if I knew John, the bar was set up and there’d be room service. Instead, my banging on the door roused him from sleep after three solid days of poker. Laughing, he didn’t say a cross word. He surveyed my three male roots-rock companions, shook his head, turned back to me and said simply, “Choose wisely.”

That’s what he’d want us all to do: Live in the moment. Follow your heart. Be kind. Generous. Help someone out. Give of yourself. Expect nothing. And always have fun.

Ironic that “The Tree of Forgiveness” is the name of the bar in that last album’s closing song, “When I Get to Heaven.” The final song — never intended to be the final song — offers a mirthful take on the afterlife, where one can kiss a pretty girl on a tilt-a-whirl, smoke a cigarette that’s nine miles long and have a vodka and ginger-ale. Pure fun, 180 proof, as effervescent in the next world as he lived life in this one.