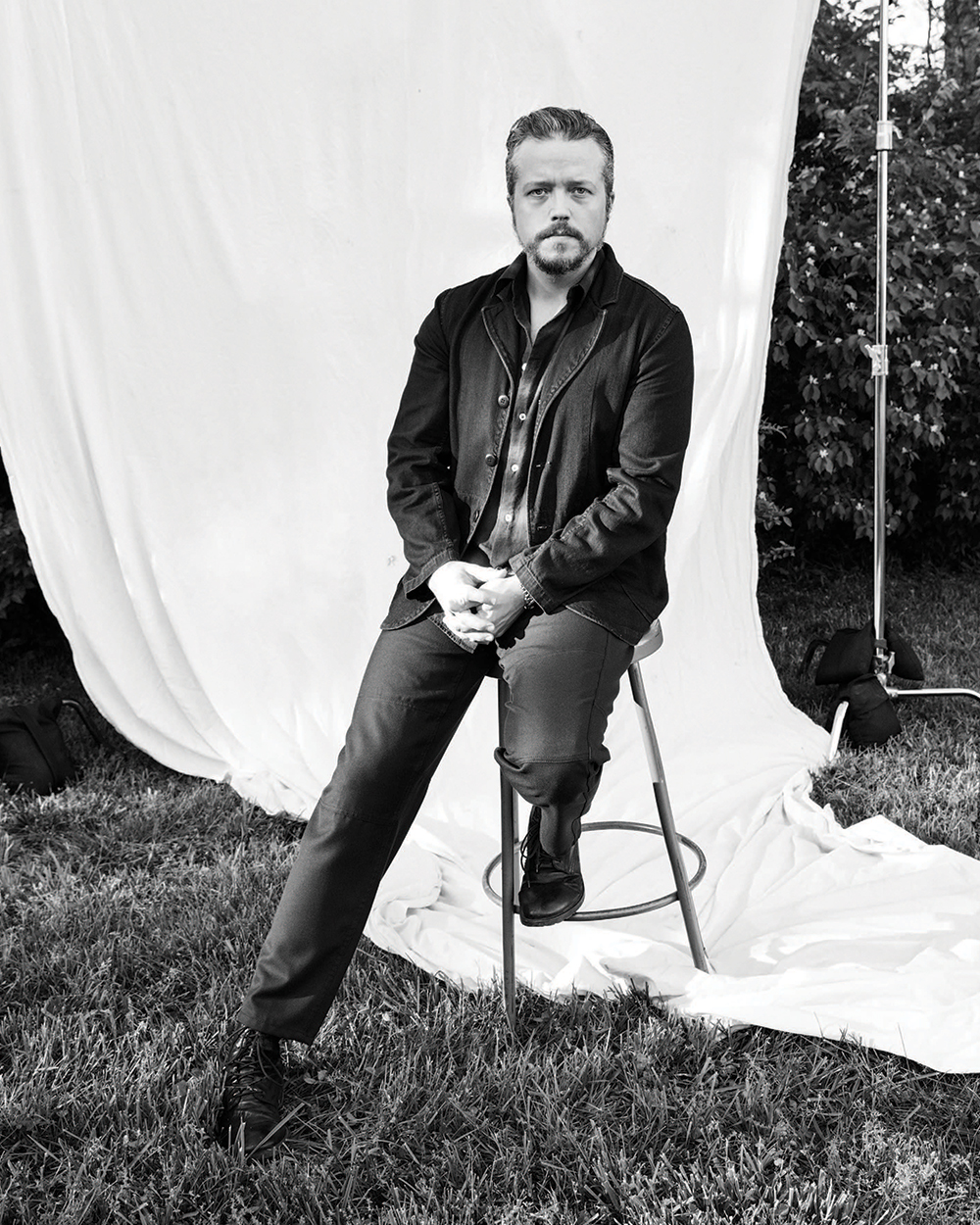

Jason Isbell on Wrestling His Demons and Honing His Message on New Album, ‘Reunions’

By Chris Willman

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – Jason Isbell is no more excited to be pinned down by genre than any other musical artist, but talk with him long enough and you might eventually arrive at a category he’s down with.

The singer-songwriter is on the phone from his home outside Nashville discussing his new album, “Reunions,” which, true to his discography, includes some deeply plaintive content. Take the track that has already become a fan favorite since he started playing it live last year, “Overseas.” It’s a song that Isbell wrote when he and his wife, Amanda Shires, a recording artist in her own right, were out on the road on separate tours. He took that disconnected, disconsolate feeling and fictionalized it into a tune about a couple that have split up and now live literally an ocean apart. There’s an inescapable sadness to it, but the reason it’s a live staple is because it does rock…

“Sad rock,” Isbell says, laughing, as if we’ve stumbled upon his true idiom at last. “Yeah, that’s me — sad-rock.”

There may be something to that: Isbell’s songs have melancholia in their DNA, by way of their lyrical undertows or minor keys, even when his themes veer toward succor and the amps are turned consolingly up to 11. But in any case, “Reunions” is reason to feel glad all over. The album, officially credited to Isbell and his longtime band, the 400 Unit, is full of emotional nourishment and moral fiber, dished up as quick narrative tapas. If he’s not “the last of my kind,” to quote one of his older song titles, then he remains among the first order of those making music that feels like it gives a damn about the way we actually live and love.

For the better part of the last decade — ever since his breakthrough “Southeastern” album in 2013 — Isbell has been thought of as one of the two kings of Americana, that loose catch-all for music that has any kind of roots basis at all. The other recent constant, John Prine, recently felled by coronavirus complications, had a lot of ebbs and flows in his 50-year career before enjoying a nice plateau of praise and attention in the final stretch. Isbell, easing into the poet-laureate rocker role at 41, seems like someone who might get to forego the ebbing part. His audience, like Brandi Carlile’s, isn’t taking the rise of a singer-songwriter of the old order for granted, which is why he’d be filling venues like L.A.’s Greek Theatre right about now, if the spring and summer had gone as planned.

He’s the first to admit it could have gone the other way. “I always figured what I do would be more of a boutique genre,” Isbell says. “I just didn’t think that people cared as much about this kind of music anymore. And I also didn’t necessarily know if I was going to be good enough or strong enough to pull that off. You know, there was a time when just getting up and going about my daily business took all the effort that I could muster,” he points out referring to the famously self-destructive patch that preceded “Southeastern.” “So yeah, I’m definitely surprised about all of it — although I’m not surprised by somebody like Brandi, because she works harder than humanly imaginable. But I’m sitting on my porch right now, and I still haven’t gotten used to where we live and how beautiful it is, or that I have this 1959 Les Paul here in my bedroom, and that I can have those kinds of guitars and go out and play shows with a big crew and lights. It never seemed like a real thing for me, because I didn’t make pop music. But it turns out there are a lot of people in the world, and if you work hard and do something well enough and get lucky, then you can find enough of them to fill up those big rooms.”

Does he want to go bigger? Isbell’s career growth has been incremental, with his last two albums, 2015’s “Something More Than Free” and 2017’s “The Nashville Sound,” both debuting in the top 10. He’s won all four Grammys he was nominated for in the last five years, although he’s never been put up for album of the year — something that might finally be rectified with “Reunions.” He caught the eye of a few more people in and out of Hollywood in 2018 when he wrote “Maybe It’s Time” for Bradley Cooper’s character to sing in “A Star Is Born.” (Although nomination-worthy, it wasn’t submitted for Oscar consideration, maybe to ensure it didn’t spoil the chances of that other “Star” song.) But going next-level isn’t really a concern, according to those around him.

“To me he’s Bruce, he’s Petty,” says manager Traci Thomas, who’s worked with him for 19 years, dating back to pre-solo days, when he was one of three singer-songwriters in the alternative Southern band Drive-By Truckers. “But radio is different today, so therefore you don’t get catapulted into more of that mainstream that used to exist. And quite honestly, he doesn’t want to be a huge superstar. He just wants to be able to make the kind of music he wants to make and prefers that we try and keep the audience as intimate as possible. It’s not like we sit around talking about things we haven’t done yet. Every once in a while we talk about something it’d be fun to do, but I remember when the goal was to play the Ryman (Auditorium in Nashville), and now we can sell out seven nights, you know? He said one time, ‘I want to be able to play arenas. I just don’t want to play them.’”

Sheryl Crow, a neighbor of Isbell’s out in Leipers Fork, Tennessee, is one of his biggest fans. For her 2019 “Threads” album, which mostly had her collaborating with older heroes like Keith Richards and Willie Nelson, she picked Isbell as one of her few younger-generation picks, to duet with her on Bob Dylan’s “Everything Is Broken.” “I can reference the greats — the Prines, the Dylans, the Pettys — but I haven’t run across anyone like him of his generation,” Crow says. “Especially if you know his story and his struggles, but even if you don’t, the lyrics that he writes pierce your heart, with the poetry that he comes up with to describe the challenge of being alive and trying to figure out how to navigate pain.”

She has one superlative for Isbell that might even put him above those veterans. “If I could have written any song in my life,” Crow says, “I wish I could have written ‘If We Were Vampires,’” an intense ballad about reconciling romantic love and mortality. “But that’s his story, and he was able to take it and write a virtual movie about it, because he’s so cinematic. The other thing is that he’s not relegated to just being a great poet or a great folk singer — he’s one of the most incredible guitar players I’ve ever heard. I feel like I’m a little bit of a student when I’m around him, which is a nice place to be at my age, to still feel like I’m learning and picking up on somebody else’s juju or mojo.”

That Crow calls him a folk singer one moment and refers to him as a kick-out-the-jams virtuoso the next speaks to how difficult it is to peg exactly where Isbell belongs. No doubt he’s the leading light of Americana, to the extent that that constitutes a genre; along with Prine, he won so many top plaudits from the Americana Music Association that he finally unofficially disqualified himself by tweeting that maybe next year they should give their top award to a woman. (They did, to Carlile.) Is he country? Not really, although “The Nashville Sound” — the title of which bore some irony that may not have been universally picked up — did get nominated for a CMA Award for best album. To watch him guitar duel in concert, on top of his previous affiliation with Drive-By Truckers, explains why he siphons fans off the jam-band circuit. To hear his finger-picking ballads on wax is to peg him as a cerebral folkie extraordinaire. Most of all, maybe, he’s best considered a callback to the ‘70s glory days when “singer/songwriter” described a mighty race of knights, not niche figures.

“It just depends on when you come along, I think,” Isbell says. “Had we come along in the ‘70s, they probably would have called it rock, and in the ‘80s it would have been country-rock, and in the ‘90s it would have been roots-rock or alt-country, and now it’s Americana. If you go back beyond that, time-wise, when everything was either classical or it wasn’t, it’s all pop.”

And he insists his music is actually more pop than you think it is, especially on the new record, where he tried to incorporate more of the sonic influences he picked up growing up in rural Alabama, listening to sounds on the radio that seemed to arrive from a world away. “I think on this record we got some sounds and tones and some melodic twists that reminded me of pop music when I was a kid in the ‘80s, without being nostalgic. As a matter of fact, this weekend I spent a few hours listening to Crowded House and Til Tuesday and Squeeze and the Cure, this magical pop music that was being played on mainstream radio then that really had some real depth to it. … I think the roots part of what I do is more informative than it is demonstrative. What I appreciate about American roots music is the intent behind it, and sometimes the subject matter; I feel like roots music does a good job of extrapolating the personal, and discussing somebody’s heart rather than just what they’re seeing around them. And I try to stick with that because that’s most meaningful to me. But sonically, I listen to a lot of things that might surprise people. I mean, when we were working on this record, I was listening to a lot of Dire Straits and Pink Floyd.”

He laughs at how his late friend Prine came to occasionally be called a country singer, too. “John had told me that when they put him on a bale of hay for his first record cover, that’s the first time he’d ever sat on a bale of hay in his life — he grew up in Chicago. And I don’t think (Kris) Kristofferson was exactly a country singer, either. I think folk music is probably the best umbrella for what we all do, as far as trying to tell stories and document things. But I think what I’ve always been, whether I was in somebody else’s band or my own… I feel like I’m a guy in a rock ‘n’ roll band.”

That point came to a head in a recent tweet of Isbell’s, a month and a half or so into the pandemic lockdowns, in which he wrote: “When this is over, I’m not doing anything without a damn drummer for 20 years.” He had just come off a 30-day streak of sitting in on the casual daily performance livestreams that Shires was doing with friends on the web early every evening. (Shires was doing these in part to raise funds for her own band members, who are sans income; Isbell, for his part, says he’s been keeping the 400 Unit on salary for now.) Asked about how he’s coping with the lockdown, musically, Isbell says, “I miss the rhythm section. I miss the horsepower. I mean, I can sit around and play guitar by myself all day, but yeah — I miss driving the big vehicle.”

He’s a designated driver now in more ways than one. The horsepower was revved up a lot more in the 2000s, when Isbell was raising hell with Drive-By Truckers — so much so that he finally got kicked out for excessive drinking, which by all accounts represented a monumental achievement by the group’s not exactly teetotaling standards. After three solo records that came and went fast enough to make it seem like he might live in the DBT shadow forever, he got sober. The first album he made as a recovering alcoholic, “Southeastern,” turned out to be the classic that marked the turning point in his career. It also signified a turn toward the acoustic, with a tone that had come to match the sensitive tenor of his lyric writing.

So much was gained with that landmark album. And maybe just a little bit was lost, too, to hear Shires tell it. She is also a member of the 400 Unit, as a fiddler and harmony singer, when she’s not off doing her solo work (or joining Carlile as a member of the supergroup the Highwomen). Shires believes Isbell took a while to reconcile his new, clean lifestyle with his older, louder sound — and while she was one of the forces intervening to get him sober, she also wanted him to keep his swagger.

“’Southeastern’ was an awesome record, but it was very much like he got a pencil and a piece of paper,” she says. “And in a way, I think that when he got sober, he had to sort of start from the basics, you know? For so long after rehab, it was him and his acoustic guitar, and the rock ‘n’ roll sort of stuff was kept more at arm’s length — because some of it could be a trigger, I don’t know, or maybe you think rock ‘n’ roll means you have to be taking drugs and getting crazy and doing things that aren’t what normal grownups do. I feel like he’s been able to bring his rock ‘n’ roll self more back into it. I’m just happy to see that there’s a way to have all of your tools available to you and still not go down the road to ruin — you can rock ‘n’ roll and not shoot out the lights.”

Isbell has been a patron saint for the recovery movement, although it’s not a subject he’s explored at any considerable length in his songwriting before the new album. Sometimes, one well-placed line is enough. On the “Southeastern” track that has endured as his most popular song, the ballad “Cover Me Up,” which is otherwise a sensual love song about sheltering-in-place with his wife, he added the aside, “I sobered up and I swore off that stuff, forever this time.” Each night on tour when he gets to that part, the crowd erupts — cocktails and 32-ounce beers spilling everywhere as they uniformly leap to applaud abstinence.

“Sometimes I forget” that these are applause lines, he says, “and then it kind of catches me off guard a little bit. It’s ironic, but it’s also kind of beautiful, if you ask me, because maybe they are drinking more than they should be, and one day they’ll think, ‘You know, maybe I should try that. Maybe I should see if sobriety works for me.’ I don’t know anybody who has looked back and said, ‘Man, I really wish I hadn’t gotten sober and stayed sober for all those years.’ I feel like people are applauding because that line in ‘Cover Me Up’ is about me being determined to not go back to that way of life. And I think people root for determination harder than they would for anything else.”

Isbell revisits the subject of sobriety in a more protracted way in the new album’s “It Gets Easier,” which takes the form of advice to a struggling friend. (The key sentiment is that resistance “gets easier, but it never gets easy.”) “This is probably the first time I’ve given it a whole song,” he says. “I did start out with the goal of writing a song for people who are in recovery but have been for a while. Because it’s kind of like a love song: You hear so much about the spark and the initial feelings about changing your life, but not a lot of people really explore what it’s like a few years down the line. I have a following that includes a whole lot of people who are in recovery, and I feel like they’re owed a song. And I think if you can come up with one that is good enough to stand up with the rest of your work, it’s a good reason to write a song.”

Not wanting it to come off as too pedantic, Isbell strived to personalize the message with some anecdotal glimpses into his own psyche. In one verse, he’s compelled to drive by the bar where he used to be a regular, and wishes that now he’d get pulled over, amid flashbacks to the times when he did, and ended up in handcuffs. “There’ve been quite a few times when a cop will get behind me and I’ll think, ‘Okay, go for it, buddy! I’ve got all my papers together here. I know where my insurance card is.’ That used to not be the case at all,” he says. “I’d have to rummage through looking for everything, and more often than not, I would be a little bit drunk and start thinking, ‘Well, how many did I have? How long has it been’ In a song like that, you do want to say something that’s widely understood, but there also should be a few inside jokes — some details where people think, ‘Oh, not everybody’s going to get this,’ because then they feel more heard themselves.”

Something else Isbell has in common with Prine is an economy of scale in his lyric writing — the ability to make you feel like you’ve read an entire short story in tightly edited verses that barely outweigh haiku. Like this heart-wrenching aside about missing someone, from the aforementioned “Overseas”: “The waiter made a young girl cry / At the table next to mine tonight / And I know you would have brought him to his knees / But you’re overseas.”

Isbell has studied Prine as a master of the form since he was a child, listening to the records of the man who would later become his and Shires’ close friend. “Sometimes I listen to John’s songs, and I think, ‘How have I never noticed that that rhymed before?’ And that’s the trick, the magic of it, making it sound like it just fell out fully formed, in the right meter and with the right phrasing. I like to use more conversational language, and so I just try to write songs that sound like the way people around me talk. And to get something poignant that still feels natural is tough. Most of the time when I hear a song and think ‘This is not a great song,’ the reason for that is that there are some things in it that would not exist if it wasn’t a song. I don’t want that to happen in my songs; I want them to feel like someone accidentally rhymed this line. And it’s a challenge.” There will be no talk about how the songs just arrive from the muse, or as a form of automatic writing, with him. “Usually on the songs that sound the most natural,” he says, “you have to put in the most work.”

Character study is Isbell’s most natural habitat, but he does veer into pointed social consciousness on a couple of songs on the new album. The opening “What’ve I Done to Help,” which has backing vocals by pal David Crosby, is a general call to compassion and action that may strike an even more particular chord now, as listeners reflect during quarantine, than it otherwise might’ve. Amid the admonition, Isbell points the finger back at himself for getting too comfortable: “We climbed to safety, you and me and the baby / Sent our thoughts and prayers to loved ones on the ground / And as the days went by we just stopped looking down / Now the world’s on fire and we just climb higher / Until we’re no longer bothered by the smoke and sound / Good people suffer and the heart gets tougher / Nothing given nothing found.”

Isbell notes that Shires initially found that verse a little too self-condemnatory. “The first time Amanda heard that song, she was like, ‘Well, that’s not exactly how we live our life. I think we try to stay as aware as we can of people who aren’t doing as well as we are.’ But,” he says, “if there’s one thing that Americans hate, it’s being told what to do. When you’re trying to give advice to an adult, you motivate people more by saying, ‘This is what I’ve done wrong.’ You have to give people an image of yourself that’s not the most flattering. You have to give something away.”

But there’s another song on “Reunions” in which he doesn’t worry so much about the tenor of his righteousness. In “Be Afraid,” Isbell isn’t timid about putting some of his fellow artists on blast for not raising their voices on vital current events, including politics. He’s put his money where his mouth is, having been the subject of a lot of Twitter trolling as the result of “White Man’s World,” a song about white privilege from “Nashville Sound,” which led some of his fans, or former fans, to essentially call him a snowflake. Rather than slink back, Isbell and Shires doubled down on their commitment to be vocal by doing benefits for Democrat Doug Jones’ successful U.S. Senate campaign back home in Alabama. Isbell’s Twitter feed is often as drolly hilarious as anyone’s, but he’s not bashful to interrupt the wryness to make some serious statements about the horrors being wreaked by the Trumpian right. He’s dismayed to see other artists holding back.

“I think when you’re writing a song like that, you have to give yourself over to it and just say, ‘OK, I’m accepting the fact that I’m telling somebody what to do right now.’ ‘Be Afraid’ is definitely a finger pointer. I mean, you’ve got fingers — sometimes you’ve got to point ’em,” he says. “There are definitely a lot of folks in Nashville and everywhere else who get to a certain point of comfort in their lives and don’t want to risk it. And even though you know that a lot of things going on out in the world are wrong, you still feel like, ‘Well, if I speak out about this, what kind of backlash am I going to get?’ And I think that’s cowardice. I very much feel that if you have a platform, it’s your responsibility to stay educated and try to use that platform to speak on behalf of people whose voices aren’t heard. That, to me, is an inarguable point. And you have to have an inarguable point if you’re going to point the finger and start yelling at people.”

He’s surprised he catches so much flack for his political and social views, although that may be part-and-parcel of being a Southern gentleman, with a lot of red-state fans, who aren’t always paying attention to where he’s coming from until suddenly they are. Isbell has an analogy for the “shut up and sing” trolling he sometimes attracts.

“Amanda and I were in Tokyo a few months ago,” he recounts. “There was this one store that looked like they were selling some kind of fancy flip-flops, and Amanda started asking about the shoes. She tried to put a pair on and the heel of her foot was hanging off the heel of the shoe by a couple of inches. And he kept saying, ‘No, this is the right size.’ Later, using Google translate, we figured out that the shoes in the Japanese shop were very specific to coming out parties, and not something that you would buy and wear unless you were participating in one of those ceremonies. But finally, after like 45 minutes of this, we figured out, ‘Oh, these are not something for us at all. It’s not going to do us any good to buy a pair of these shoes.’ So we thanked the man and we left.

“And I think very often you will have fans who stumble in thinking that you’re selling one thing, when you are in fact selling something completely different. So I see some people who walk into the shop and think, ‘Oh, look at this country singer.’ Then they look around for a minute and they get confused. And then they realize: ‘These shoes are not for me.’ And usually in that situation, your job is to thank the proprietor and then leave and go to a shop that is for you. You know, I’m not going to stand there in front of this Japanese man and start yelling at him because none of those shoes fit my wife’s feet. They’re not supposed to, so I’m going to go somewhere else. Sometimes I wish listeners would do the same thing with music. Sometimes I’m like, ‘Why are you still standing in this store? Go down the street and find what you’re looking for! We’re still be open — we’re fine.’”

Isbell admits he has to regulate the intensity of his feelings about where America seems to be headed. “There’s a point at which, where if I start worrying too much about big picture things, it makes me less effective as a father, a husband and a friend, so I have to try to keep on the correct side of that line. if I put all my energy into trying to turn this humongous ship, you know, it’s not going to turn based on what I’m doing, and I’m just going to drive myself crazy. So I have to do as much as I can without going nuts.

“But that being said, I think the virus is very much a black light. To paraphrase Megan Amram, who I think is probably the funniest person on Twitter, the virus is just showing us what we were doing wrong. And it’s going to take a lot to get back to where we were. And I don’t think we’ve ever achieved anywhere near the potential as a nation that we had when we first started out. I mean, there’s always been a huge number of people who were disenfranchised, who weren’t included in the American dream, and now that’s really becoming more and more obvious.”

Little to none of the songs themselves are political, in any case… unless you consider the quality of empathy to be political, in itself, in which case maybe all of them are. “I think it all comes down to being aware and trying to understand people who have different experiences from yours,” Isbell says. “And to me, I think if you’re only (self-) reflecting and you’re not trying to understand what somebody else’s experience is like, as a songwriter, I think you’re a fraud.”

With that said: reflection becomes him. Isbell fans come to him partly for the rich detail of the character songs, like “Elephant,” the “Southeastern” number about being partnered with someone who is dying of cancer. And they come to him for the songs that blur the difference between fact and fiction, like the new album’s “Dreamsicle,” which is about being a constantly moving child of divorce, only some of which applies to his wonder years. “I remember first hearing Prine singing ‘Angel from Montgomery’ and thinking, ‘He’s not an old woman!’ And then all of a sudden I thought, ‘Oh, you can do whatever you want with this. You don’t have to talk about yourself exclusively, or talk about somebody else exclusively.’ You can put it all in one song, as long as you get it right.”

But the fans also come for the songs that have very little narrative filter, that seem to spring very much out of his own experience. Two of the more fiercely romantic of these, “Cover Me Up” and the Sheryl Crow-endorsed “If We Were Vampires,” are songs that produce such obvious chemistry between Isbell and Shires on stage that you may wonder if it’s even possible for them to be connecting through them as deeply as they seem to be each night.

“I don’t think we ever have to fake it, because no matter where we’re at on a personal level, there’s still something sacred about the connection there,” Isbell says. “I mean, I think about Stevie (Nicks) and Lindsey (Buckingham) being on stage with Fleetwood Mac for all those years and still singing to each other. And I know there’s a level of showbiz that goes into what they did, because they certainly haven’t always gotten along. But as people who try to write and perform with all the honesty that we can muster, even if she’s pissed at me that night, for those four minutes, I think both of us try to put ourselves in the place that we were in when those songs were born. Hopefully it reminds the people in the audience that there’s still some sort of center and some sort of route for your relationship that might be worth reminding yourself of pretty often.”

Shires doesn’t want anyone to over-idealize them just based on that on-stage smoldering. “Sometimes I feel like people might paint us as the perfect happy couple,” she says. “If somebody is in their marriage, looking at us and thinking, ‘Oh, they have so much fun together all the time — they don’t have trouble,’ I don’t want them to go off getting divorces because of some unattainable thing that doesn’t exist. We’re very much in love. But it really is a lot of work to be as close as you are to a person.” She says the making of “Reunions” had its tense moments: “There was a lot of pressure with this record that he was wrestling with, and it took him awhile to admit and be comfortable talking about, whereas I’m like, ‘Let’s talk about it!’ But we did it, and I think the work we did is beautiful.”

Probably the loveliest of many lovely songs on the record is “St. Peter’s Autograph,” which came out of an emotional impasse they experienced during the making of the album. Shires admits she had some reservations about having such a personal tune included on “Reunions.” “The things you talk about in private, you get real protective over,” she says. “There were moments when I was listening to that song where I was like, ‘I’m never going to tell him anything ever again!’ But talking about stuff is easy for us, and maybe if it’s not so easy for other folks in their relationships, I like the idea that maybe it helps make conversations open up.”

“St. Peter’s Autograph” was sparked after a friend of the couple’s, Neal Casal, committed suicide last year. Isbell, by his telling, started to become upset or jealous that Shires, who was closer to the late and lamented musician, was not moving on from the intensity of her feelings about it as quickly as he did.

Says Isbell, “Probably the main topic of discussion in that song is this idea of appropriate grief, and that concept as a fallacy. It’s been my next-level maturity, to let go of this idea that her sadness over somebody that she has lost, who was very important to her, is somehow related to my emotions or subject to my approval. I think a lot of that goes back to toxic masculinity, the idea that somehow your partner is your possession. Allowing somebody to feel all their feelings and not assume that that has anything to do with you is one of those things that sort of separates the adults from the kids who are walking around pretending to be adults.”

How many songs have ever been written about a couple reconnecting and getting closer after a husband has caused a rift by mansplaining the acceptable stages of grief? “It has not been covered a whole lot,” laughs Isbell.

Then he corrects himself, hesitant to take too much credit for ingenuity in tackling previously unexplored topics. “It’s probably been covered by, like, Billy Joe Shaver or Willie Nelson,” he says, “and they’ve just done it in a way where you thought they were writing about a cowboy.”