Inside the Battle to Take “StarCraft II” Back From Its Korean Overlords

By Will Partin

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – Esports is built on stories.

From “Overwatch” to “Dota 2” to fighting games, every community has its own account of its history, a latticework of narratives that helps give shape to the often messy and inscrutable world of competitive gaming. Though each scene is, ultimately, distinct, one story that echoes across multiple games is the rivalry between players based in East Asia and those in the rest of the world. The specifics shift – “Dota 2” has China, fighting games, Japan, and “League,” South Korea – but, for a variety of reasons, waxing and waning in intensity as esports has taken root across the world, East Asian players have often had an edge on their Western counterpoints. Even so, this rivalry is longest and, perhaps, felt most acutely, in “StarCraft,” where South Korean players have set the bar for the game that made modern.

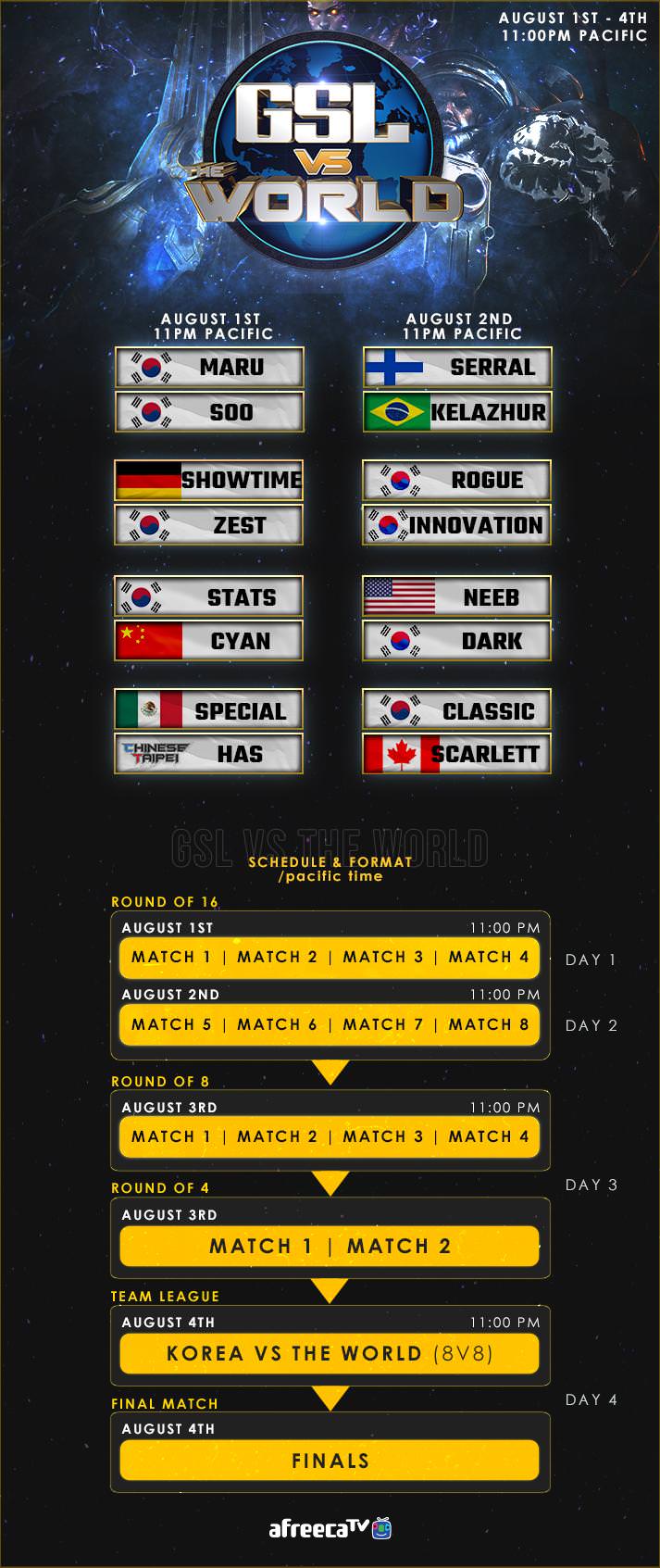

Until now (maybe). This weekend in Seoul, South Korea, GSL vs. the World will test conventional wisdom about “StarCraft’s” regional rivalry. Chosen by a mix of invitation and fan vote, eight of the best “foreign” (read: non-Korean) players and eight Korean teams from the GSL – the Global StarCraft II League, the most prestigious league in “” and which has run without interruption in South Korea since the game’s debut in 2011 – will compete in a 16-person single elimination bracket. It aims to settle, for now, the question of whether foreigners can stand against the Koreans at their own game.

That such a question can be asked – let alone as one whose conclusion is not forgone – is something of a minor miracle for “StarCraft II.” But you need a bit of history to see why. When

Variety

reported, last month, on the rise, fall, and resurrection of “StarCraft II,” one of the central challenges Blizzard faced was managing an esports ecosystem where the overwhelming majority of talent was concentrated in a single country. How was the company supposed to balance celebrating the surfeit of talent in the Korean peninsula alongside cultivating a worldwide competitive ecosystem?

Though there are many explanations for South Korean excellence in professional gaming, the best ones are historical. As a result of a number of trends and events in the late 90s – the Asian financial crisis, the proliferation of net cafes, a population surge, wide youth unemployment, etc. – South Korea was primed for esports. National conglomerates quickly monetized the budding subculture, bringing financial and social legitimacy to professional gaming. A robust competitive infrastructure followed, enabling South Korea to professionalize its homegrown talent better than any other country in the world. Though some would chalk South Korean dominance up to “innate talent,” it’s really a matter of the mode of production. Everyone is more likely to be made by history than to make it for ourselves.

This history set the stage for “StarCraft II”, and the immediate leg up South Korean players had on their foreign counterparts.

“In the early days of ‘StarCraft II,’ the game was fresh, so nobody knew exactly how it was supposed to be played,” remembers Ilyes “Stephano” Satouri. “Koreans tended to have an efficient system of gaming houses with coaches and maids, whereas the rest of the world was mostly by themselves.”

Korean players would be in the gaming house playing for more than 10 hours a day, the practice regimen was less hardcore outside of South Korea. Koreans mastered the mechanical aspects of the game way faster, which gave them quite an edge.”

Such an edge, in fact, that many North American tournaments initially limited or outright banned South Korean competitors in order to protect foreign talent and support their growth. And, for a while, the strategy worked.

“Koreans only had to care about the game itself. All the annoying little things like cooking and cleaning were taken care of,” explains Satouri. “Slowly, though, the rest of the world caught up with this system.”

As “StarCraft II” grew and the foreign scene stabilized, organizations like Evil Geniuses and Team Liquid were able to support Korean-style team houses. With those came new results: a handful of talented foreign competitors –

Greg “IdrA” Fields

,

Johan “NaNiWa” Lucchesi

,

Chris “HuK” Loranger

, and, later,

Stephano

and

Sasha “Scarlett” Hostyn

– found themselves able to compete on more-or-less equal terms with top Korean talent. Though Koreans still won the majority of international tournaments, “StarCraft’s” interregional rivalry was heating up to the delight of fans across the world.

Then, in 2013, Blizzard introduced the World Championship Series, a standardized global circuit that allowed any player (including Koreans) to compete in whatever region they desired. Many Koreans, looking for an easy payout, took up residence in North America and Europe, where the proceeded to crush the homegrown talent. The effect on the foreign scene was devastating. Not only were foreign players effectively cut off from prize money – a key component of their and their teams’ livelihood – but one of “StarCraft”’s founding narratives came crashing to an unceremonious end. “StarCraft II” was, once and for all, the Koreans’ turf. With that settled, many fans lost interest and moved on to other games.

“[The GSL] lost a lot of its star power,” said Dan “Artosis” Stemkoski in an interview with

Variety

earlier this year. “And WCS never picked up [in foreign markets] because it was just a bunch of Korean guys bashing everyone.”

The story could have ended there, but, humbled by its missteps, Blizzard introduced region locking in 2015, which forced players to compete in regions according to their nationality, opening a new chapter on the rivalry between foreign and Korean players. The company also took steps to support a new team house in South Korea, where foreign players could train in ideal conditions against each other and elite Korean talent. Though these moves were initially derided by many as a violation of the principles of meritocracy, their effects were immediate.

Slowly but surely, foreign players began to claw their way back into relevance. Within two years of Blizzard’s redesign, Alex “Neeb” Sunderhaft became the first foreign player to win a “StarCraft II”

tournament in South Korea. Later, Scarlett won a Gold Medal for Canada at the Olympic-adjacent tournament, IEM PyeongChang. And, this year, Finnish Zerg Joona “Serral” Sotala, has won back-to-back premier events (WCS Austin and WCS Valencia), giving him a decent – if contested – claim to be the best player in the world.

“If foreign players come to Korea to practice, they are definitely able to improve,” said Cho “Maru” Seong Ju, a professional “StarCraft II” player for the elite Korean team Jin Air Green Wings, in an interview with

Variety

. “

I don’t really watch foreign players play that much, but I think they improved in all aspects of the game

.”

“I believe the gap is narrowing,” echoed Satouri over Skype. “Koreans had the edge due to their mechanics, but, given enough time, those will be mastered by everyone.”

It would be heartwarming to say that, with a little push from Blizzard, Western players were able to dig in their heels and claw their way up to a level of skill once attainable only by Koreans. But that would only be half the story. The other half is what happened to the Koreans when region locking took away their surest source of money.

In 2015, Korean pros who had been competing abroad largely returned to South Korea, where “StarCraft’s” diminished state was unable to support the influx of talent. Many excellent players outright retired, while others got caught up in a

nasty match-fixing scandal

. StarCraft ProLeague, one of the game’s longest-running and most storied tournaments, ended

with a whimper

in fall 2016. So disillusioned by “StarCraft II”, others tried to revive “StarCraft: Brood War,” casting back to a golden age that had long since receded into memory.

“Korean players are having a hard time practicing after most of the teams got disbanded, since everyone was so used to living in team houses

, said

Ju

. “S

ince now almost all the pro teams in Korea have disbanded, Korean players have to practice alone. The number of tournaments has also decreased, which is also making it difficult for Korean players.”

In other words, just as infrastructural shifts that benefited foreign players led to improved results, the decline in formal support from Korean organizations put, for the first time, Korean players at a structural disadvantage against their foreign counterparts. The state of “StarCraft II” today isn’t simply that a cadre of foreign players have, through perseverance, earned the ability to go toe-to-toe with their Korean rivals; it’s that the infrastructures that make professional competition in “StarCraft II” possible are more equal than at any point in the game’s history.

This brings us back to GSL vs. the World, which might, oddly enough, be “StarCraft II’s” way of coming full circle, or close to it. It recalls an earlier moment in the history of the game when foreign and Korean players had access to if not equal than at least comparable resources, and results to match. As with any sport, it’s never just the players who are competing, but the ecosystems that build up around them.

Though the collective strength of the Korean field is, in all likelihood, higher than their foreign quarry, both Satouri, who is not competing at the even, and Ju, who is, agree that Serral is the player to beat at GSL vs. the World.

“I have faith in team World. This year is our moment to shine, and by our, I mostly mean Serral’s! He has been getting better than any of us lately,” said Satouri. “He’s mastered almost every single aspect of the game, and we barely ever see him make a mistake.”

“Since I received an invitation to GSL vs. the World, I really want to do well and I’m looking forward to playing against Serral. He’s winning everything in the Circuit, and I’m curious to see how we’d match up against each other.”

(Serral, for his part, politely declined to be interviewed for this piece, citing preparations for the tournament. In a strange turn, Serral prefers to practice in monkish isolation in Finland. Despite the role that infrastructure plays in determining players’ fortunes, the importance of individual preference and talent cannot ever be completely denied. There are no guarantees in history).

But whoever comes out on top this weekend, GSL vs. the World is a reminder that no story is ever quite over, and a sign of the progress “StarCraft II” has made since its ignominious decline in the mid-2010s. Fifteen of sixteen players will, by definition, lose; but for “StarCraft II”, it’s a win no matter what.

And, hell, it’s about time.