Inside ‘Beyond a Steel Sky,’ the ‘Beneath a Steel Sky’ Sequel (EXCLUSIVE)

By Steven T. Wright

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – “Beneath a Steel Sky,” the cult 1994 adventure game, is getting a sequel, UK-based game developer Revolution Software announced at Monday’s Apple keynote in Cupertino, California.

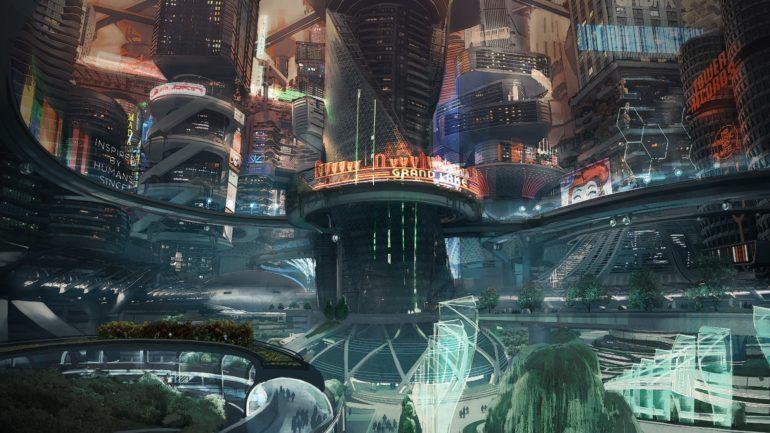

The project sees a return of the creative duo behind the original: lead designer and head of Revolution Charles Cecil, and comics artist Dave Gibbons, best-known for collaborating with Alan Moore on the seminal graphic novel “Watchmen.” But while the original’s cyperpunk point-and-click puzzle-solving has fallen out of favor in the intervening decades, its creators say that the sequel – dubbed “Beyond a Steel Sky” – will take a far different approach to how the player interacts with its gleaming metal spires and twisted towers.

“We very deliberately decided not to call it ‘Beneath a Steel Sky 2,’” says Cecil. “For one thing, people associate it with that point-and-click style. For another thing, we want people to be able to approach this game without even having heard of the original. It’s a continuation of both the themes and story, but we find that the themes are more important.”

“That’s a thing I see in comics all the time,” echoes Gibbons. “When you respect the continuity, you make all the fans happy, and that’s good, but it keeps out all the new people. It’s a real problem at times. With ‘Beyond,’ we’re trying to make a game that people who maybe weren’t even alive in 1994 can appreciate. If you’ve played the original, it will enrich the experience, but it isn’t absolutely necessary.”

In accordance with more modern approaches to the adventure genre exhibited by “walk-’em-ups” like “Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture,” Cecil says that “Beyond” will feature fully 3D environments that the player can stroll through and interact with, with full camera control. Gibbons takes great pains to note that the studio has developed an entirely new tool to facilitate a comic-book aesthetic while still taking advantage of this newfound depth and technology. While Cecil isn’t comfortable talking more specific than that just yet, he says that the team’s goal is to embody the spirit of the adventure games that put them on the map, such as their lengthy “Broken Sword” series, emphasizing that the non-violent nature of the genre has allowed the studio to garner a diverse fanbase broader than that of more traditional action games.

Despite the duo’s stated goal of producing a work that stands apart from its well-known predecessor, “Beyond” stars the returning protagonist of the original game, a small-time engineer named Robert Foster. While “Beneath” dealt with the rampant sentience and breakdown of a “Neuromancer”-esque AI called LINC that haunted an entire city, Cecil and Gibbons say that its follow-up will deal with more pressing questions of social control and privacy under the watchful eye of the supposedly-benevolent, omniscient artificial-intelligence that Foster installed at the conclusion of the first game. In particular, Cecil describes how an AI might view the ideal human society by referring to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, a famous triangle-shaped construct in sociology that attempts to explain how the fundamental needs of human beings build off each other. Since an AI would ostensibly follow all those rules as consistently as possible, it would rigidly adhere to that hierarchy at all times, even when it might seem counterproductive.

“You look at something like a social credit system, for example,” says Cecil. “Now, us in the West look at those kinds of systems, and we think of them as particularly Orwellian, very scary stuff. But when you look at some of the data, you’ll find that some of these systems are surprisingly

popular

. And when you ask them why, they say things like, ‘well, it means that people have an incentive not to litter, to act more orderly in society.’ To an AI that tries to view these things ‘objectively,’ that sort of system makes a lot of sense. The entire game is about how an AI would look at human society and try to make it into a utopia, and what might happen because of that.”

Throughout our interview, Cecil repeatedly references George Orwell’s classic work “1984” as a major touchstone for this upcoming game’s themes. But as Cecil himself admits, while Orwell’s work gave a vocabulary to the sophisticated spin-techniques that would spring from the decades that followed, the totalitarian doom-state that Orwell described has only materialized in select countries, and often for limited periods of time. Instead, he points to another dystopian work as a source of inspiration, Terry Gilliam’s cult 1985 film “Brazil,” which depicts the byzantine world of bureaucracy as flashy and absurd in its inherent nihilism. Cecil says that the anarchic tone of the film helped him inject the signature dashes of humor in “Beneath,” a major part of its lasting charm. Though the two creators admit that building a game around these ever-relevant issues might invite some controversy, they say they’re trying to ladle them in as thoughtfully as possible.

“We’re trying to reflect society without making too many judgments,” Cecil says. “This isn’t supposed to be an extremely political work or anything, but it does deal with these social issues. It’s the most ambitious game that we’ve ever written at Revolution, for sure, but it’s not trying to push any agenda. Rather, we want to explore them.”

“I’m certainly not trying to write a political tract,” Gibbons says, laughing. “More of an interesting story.”

As the two developers continue to work on the hotly-anticipated game – which has been rumored for quite a while now – they marvel back on the singular impact that “Beneath” has had on their careers, even 25 years later. For Gibbons, as a creator who usually works in another medium, the most striking difference between the two experiences is the level of tech involved. As he recalls, the studio in York didn’t even really have internet back in the early ‘90s. “Being able to post something in Slack and get instant feedback is just so much better,” he says. “It’s like night and day.”

According to Cecil’s recollection, when Microsoft introduced Windows 98, “Beneath” ceased functioning on many computers, but the studio was too wrapped up in the development of the first “Broken Sword” game to pay too much notice. It was only after a computer science student named Ludvig Strigeus unveiled a piece of software known as ScummVM in 2001 that allowed enthusiasts to play their aging adventure games on a modern-day PC that the game experienced a second wave of interest. Cecil attributes the decision to make “Beneath” available as a free download in 2003 as one of the core reasons why so many people continue to clamor for a sequel. “It was the only game that a lot of people knew about that was free at the time,” he says. “We weren’t trying to, but we got a lot of interest.” For those fans, Cecil says he’s glad that they’re finally going to be able to fulfill those wishes – he just hopes the game can live up to the now-mounting hype.