Inside an Editor and Negative Cutter’s Journey to Stitch Together Orson Welles’ Final Film

By Iain Blair

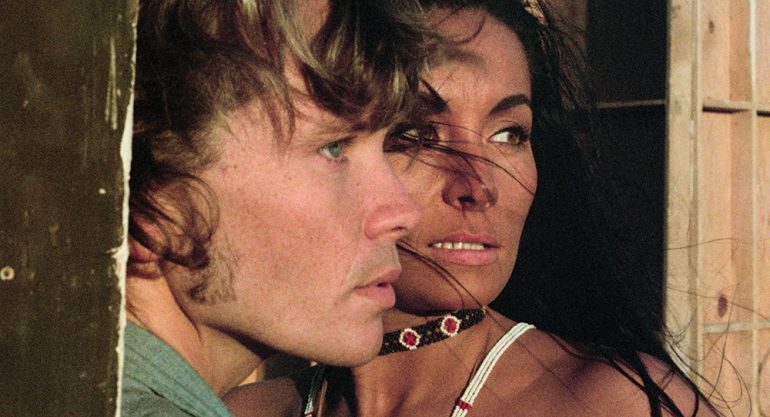

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – When legendary director Orson Welles began shooting “The Other Side of the Wind” — an art-imitates-life story about a famous Hollywood director (played by John Huston) struggling to finish his final masterpiece — in 1970, he could never have predicted the long and winding road his own film was about to travel. Plagued by financial and legal issues, the production, which spanned years, was never completed, let alone released. Welles died in 1985.

Ultimately, more than 1,000 reels of film languished in a Paris vault until 2017, when producers Frank Marshall (a production manager on the initial shoot) and Filip Jan Rymsza spearheaded efforts to finally complete the film, which was released theatrically and streamed by Netflix on Nov. 2.

To reach this point, a team of including Oscar-winning editor Bob Murawski (“The Hurt Locker”) and negative archivist Mo Henry, the negative cutter of better than 300 films, notably “The Dark Knight” and “The Matrix,” labored for more than a year to painstakingly assemble the puzzle left behind by Welles almost 50 years ago.

“I had to go through nearly 1,100 cans using magnifying glasses and try to put them in sequence,” says Henry. “So you could get a can with some 50 strips of 16mm negative in it, and we’d try to find slates where possible, although many were removed, which is another irony, since the film mentions that — and then it happens in real life. It felt like Orson’s joke from the grave: a film within a film within a film.”

Henry and her team faced additional challenges. “It was all different film stocks,” she adds. “At first it was thought he used such a wide variety because the budget was small and he’d shoot with whatever was available, but then it seemed to be part of the whole trippy design, with black and white, color, 35mm, 16mm — this mishmash of material.”

The cutter adds that the enormous amount of film was difficult to handle after 40 years in storage, with some of it very damaged. “And back in the ’70s,” she adds, “they didn’t have bar codes, so we had to do it all by hand with notes.”

Once all the raw footage was assembled, Technicolor scanned it and cleaned it up, and then Murawski began editing, “which took about six months,” he reports. “Orson had asked Peter Bogdanovich, who also stars in the film, to finish it if anything happened to him, so he was the de facto director, and we all worked hard to stay true to what Orson would have wanted. And as he’d shot it over a six-year period, there were lots of changes and lots of versions of the screenplay.”

The puzzle was further complicated by the huge amount of material Welles shot for the film-within-a-film, adds Murawski. “It’s a visual treat and very Fellini-esque in parts, and Orson obviously loved it, as he’d actually edited all of it. But we had to cut it down quite a bit so it didn’t overshadow the main story and emotional center of the film.”

Despite all the work, Murawski calls the film a career highlight. “Who,” he posits, “gets to co-edit a film with ?”