How Karlovy Vary Fest Maintains Its Cultural Relevance 30 Years After Velvet Revolution

By Peter Debruge

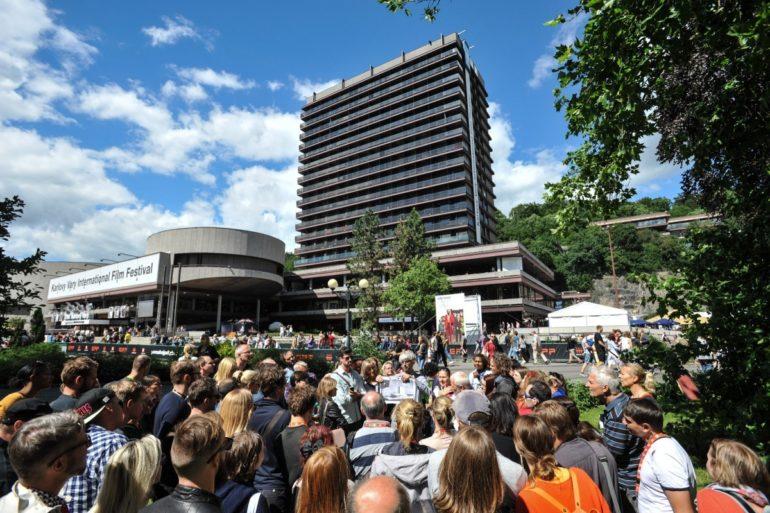

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – In the middle of the Czech spa town of Karlovy Vary stands a massive Brutalist building, the Hotel Thermal, which has housed the Int’l Film Festival since the late ’70s (the festival itself started three decades earlier, alternating in its early years with a sister event in Moscow).

It is here in the Thermal, on one of Europe’s biggest screens, where I have seen movies that rival those debuting at Cannes six weeks earlier — discoveries such as German director Jan-Ole Gerster’s demanding-mother drama “Lara,” winner of two prizes (a special jury award, the equivalent of second place behind Crystal Globe-winning “The Father,” and best actress to leading lady Corinna Harfouch, who earned the same honor 31 years earlier), and Hong Khaou’s “Monsoon,” a subtle, soulful rumination on the many facets of identity, starring “Crazy Rich Asians” heartthrob Henry Golding as a Vietnamese refugee raised abroad, struggling to reconnect with his mother country.

Karlovy Vary is the first major stop after Cannes where the great French festival’s most essential films (such as Palme d’Or winner “Parasite”) can be seen by non-industry audiences, many of them curious young cinephiles — open-minded twentysomethings from the surrounding region — who set up camp in town for the 10-day event. Of course, Karlovy Vary doesn’t have the resources or the clout to rival Cannes, and it doesn’t try to, limiting the black-tie events to opening and closing night. Still, in its way, this strange structure, the Thermal Hotel, serves as the festival’s equivalent of the Grand Palais, looming tall and solid, an imposing concrete monstrosity flanked by two circular conference areas.

Viewed from above, the mix of corners and curves suggests a giant film camera — a task for a drone shot, a device which now factors into at least half the films I saw in Karlovy Vary, or anywhere else, this year. (Better yet, look it up on Google Maps for the overview.) Architecturally speaking, the Thermal is unlike anything else in a destination that otherwise might have doubled as a Disney fairy tale village: a town bisected by a canal, on either side of which five-story pastel-colored façades decorated like wedding cakes form a kind of corridor down which tourists and festival attendees walk between movies.

If these gingerbread buildings suggest something enchanted and elitist (the Grandhotel Pupp served as the title resort in “Casino Royale,” while the hilltop Hotel Imperial inspired Wes Anderson’s “The Grand Budapest Hotel”), then the Thermal is a reminder of another era, back when the Czech Republic found itself under Communist control. It is the 20th-century brain center of a place that seems frozen in time, although this year marks the 30th anniversary of the Velvet Revolution, which restored democracy to the country, and with it, the chance for Czechs to reconnect with art and cinema from the rest of the world. Just weeks before the festival, 120,000 demonstrators turned out to protest prime minister Andrej Babiš in Prague — a sign of ongoing political engagement in a country that doesn’t take democracy for granted.

Year after year, KVIFF (as festival staff dub it, though visiting Americans seem to prefer the tongue-twister that is “Karlovy Vary,” the name of the spa town whose Nazi occupiers once called “Karlsbad”) brings a curated selection of festival treasures to Czech audiences, along with a great many world premieres from practically every corner of the world. Karlovy Vary is positioned roughly midway between Cannes and Venice, fellow “A” festivals which command first choice of the most coveted new films, which forces artistic director Karel Och and his team to get creative about where to find a few dozen quality premieres for the festival’s three main competition strands: narratives, documentaries and a strand known as “East of the West.”

If Karlovy Vary has a niche, it is this latter geographical specialty: still Europe, but farther inland, focused on countries shaped by conflict, whose long-anemic film industries have been stirring to life in recent years. Apart from Romania, whose new wave of talent has received enthusiastic support at Cannes, this region has received relatively little international attention from the global film community — which is where Karlovy Vary comes in, showcasing emerging directors whose everyday dramas (like Bulgarian prize-winner “The Father”) grapple in ways explicit and implied with their often-ugly 20th-century history.

When one of these films is really remarkable, Och tends to elevate it to the main competition (à la Bulgarian duo Kristina Grozeva and Petar Valchanov’s “The Father” this year), making “East of the West” a kind of “Un Certain Regard” of emerging Eastern European filmmakers. Frankly, I find many of these movies quite challenging, as I’m not expert enough in the human rights violations perpetrated by Serbians, Russians, Turks and so on. For the last 75 or so years, Nazis have served as a kind of all-purpose antagonists in European cinema, but the continent’s history is far more complicated, and Karlovy Vary is an excellent place to start in terms of educating oneself.

There are valuable lessons to be found in Lendita Zeqiraj’s tough-going “Aga’s House,” for example, which confronts the shame and silence surrounding the mistreatment and sexual abuse of Kosovan women. In “Oleg” (which debuted in Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes, but stood out more prominently at Karlovy Vary), Latvian director Juris Kursietis paints a chilling picture of a kind of 21st-century slavery, following a legal-immigrant butcher to Belgium, where a workplace incident leaves him jobless and exploitable by an unfair system.

The most eye-opening discovery for me was a classic Czech film, Juraj Herz’s 1969 “The Cremator,” an early and deeply unsettling critique of the country’s complicity in the Nazi cause. Over the course of the film, the main character, an oily and deeply amoral funeral worker played by legendary Czech actor Rudolf Hrušínský, becomes so brainwashed by the promise of Germanic superiority that he turns on his half-Jewish wife and “Mischling” children. The film’s fragmented style — in which a linear plot is rendered ironic via brisk cuts and disarming closeups — still retains its avant-garde edge half a century later, as does the film’s daring political critique, which escalates to a degree I hadn’t imagined possible.

For the curious, the same 4K restoration of “The Cremator” will play the Metrograph in New York next month. The film’s inclusion at Karlovy Vary underscores the festival’s unique connection to classic cinema: During the Soviet era, Czech audiences were denied access to much of Western and world cinema, and one can sense the ongoing engagement with and curiosity toward important works from the past — a kind of ongoing cultural excavation in which these films are not being revisited so much as seen for the first time.

Retrospective sidebars exist at many festivals (Cannes Classics premiered “Forman vs. Forman,” an essential documentary on Czech maestro Milos Forman, for example). Because the average Karlovy Vary attendee tends to be rather young, that makes this an ideal crowd with which to share restorations by the Film Foundation (Stanley Kubrick’s “Paths of Glory”) and the Academy (“Detour,” that most overwritten of films noirs). In the present market, the challenge of keeping these classics alive can be every bit as difficult as creating new work, and Karlovy Vary is deeply committed to both causes.