‘Happy Happy Joy Joy: The Ren & Stimpy Story’: Film Review

By Dennis Harvey

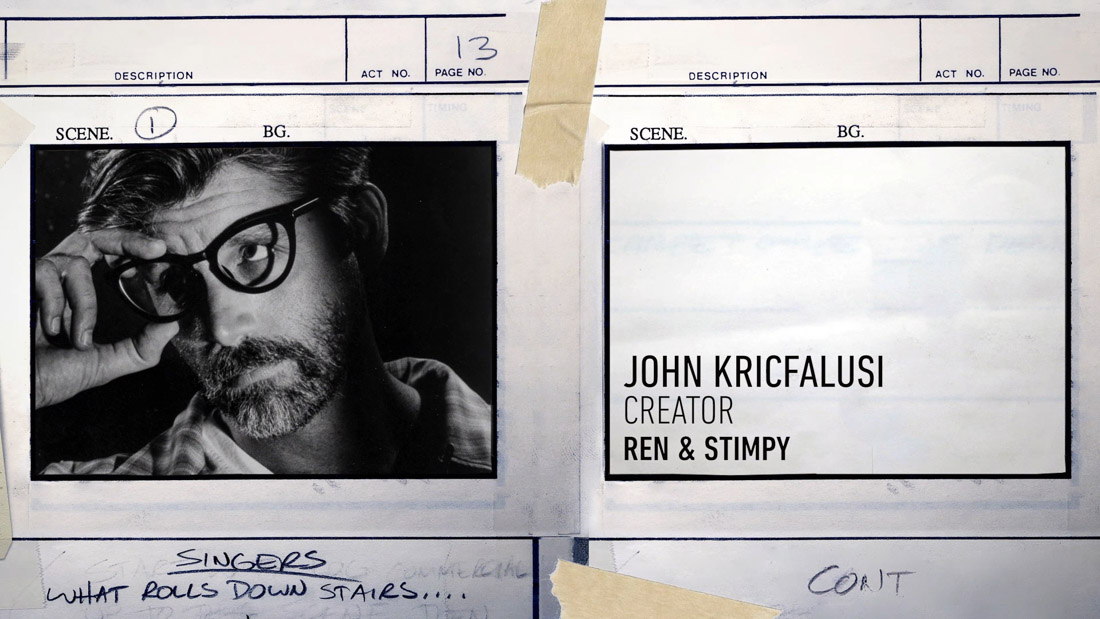

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – For many the 1990s were the Age of Irony, with hipster cultural touchstones like Spy magazine and the TV show “Strangers With Candy” helping make snark the preferred flavor of the day. “The Simpsons” was also a big player in that area, yet arguably no cartoon series before had been quite so postmodern as “The Ren & Stimpy Show,” which premiered a couple years after it in 1991. While Matt Groening’s creation still chugs on decades later, way past its pop-phenomenon peak yet remaining a valuable Fox commodity, John Kricfalusi’s was short-lived — and his own control of it even shorter.

“Happy Happy Joy Joy” is both an homage to an inspired endeavor and a cautionary tale illustrating how even the greatest popular success can be brought down by unchecked ego, perfectionism and “artistic temperament” at the top. Feature debutants Ron Cicero and Kimo Easterwood’s documentary is a very entertaining recap that grows more disturbing as it wades into the dysfunctional behavior that doomed the show, and still somewhat taints its legacy. It should prove a hot item among the series’ many past and ongoing fans.

A compulsive drawer fascinated by animation from an early age, Kricfalusi formed Spumco Studios in 1988, though his pre-“Ren” professional activities are barely noted here. Assembling a group of talented specialists equally dissatisfied with the cheap, generic, merchandizing-focused toons that had dominated children’s television for decades, they hoped to bring back the artistic glory days of “golden era” Looney Tunes and such. While uninterested in the specific concept he sought to pitch, Nickelodeon executive Vanessa Coffey encouraged Kricfalusi to develop two subsidiary characters that caught her fancy.

Thus was born “The Ren & Stimpy Show,” variously described here as “If Tom and Jerry opened up a portal to Hell” and “A dog and cat are friends but live on the precipice of insanity and death.” It took the wild physical and psychological exaggeration of Bob Clampett’s classic Warner Bros. shorts to berserk new extremes, with the misadventures of psychotic, asthmatic Chihuahua Ren (initially voiced by Kricfalusi) and dim, loyal, hapless cat Stimpy (Billy West) inevitably bending toward the violent and gross.

The content was envelope-pushing enough to create public controversy (particularly as it was on a child-targeting network), as well as incessant battles with Nickelodeon brass. But that crazed absurdism, combined with a striking hand-drawn visual style, also made for an immediate ratings hit and object of faddish obsession. Kricfalusi’s gifted staff were gratified to be working on something so cutting-edge, even at the cost of enduring extremely long hours and a somewhat tyrannical, abusive boss. But their environment grew worse when he broke up with girlfriend-collaborator Lynn Naylor, who’d been a mediating influence. And when the network upped its second-season episode order in response to overwhelming demand, Kricfalusi became even more maddeningly difficult. Coffey says she had no choice but to terminate his and Spumco’s involvement when he flatly refused to cooperate with any future deadline or budgetary limitations. Company co-founder Bob Camp was promoted to creative director on the show’s subsequent seasons, which ended in 1995 and are generally regarded as inferior.

It was a spectacular wipeout that Kricfalusi took hard. But the role he assumed of sensitive genius thwarted by crass moneymen is somewhat undercut by co-workers’ latter-day testimony, as well as glimpses here of his later work, which was so nastily “extreme” (including a “Ren & Stimpy Adult Party Cartoon” canceled after just three episodes) that it suggests Nickelodeon’s squeamishness actually did his sensibility a huge favor.

At Sundance the documentary directors’ noted that “Happy Happy Joy Joy” was virtually completed almost two years ago when BuzzFeed broke the story that fans Robyn Byrd and Katie Rice had been manipulated into abusive relationships with Kricfalusi while still teenagers. This revived tales of his creating a hostile work environment even by Hollywood standards while adding a new level of pederastic ick. Soon after, the hitherto uncooperative Kricfalusi (as well as Byrd) agreed to extensive interviews, which were woven into the smoothly restructured feature. He duly strikes a posture of shame for his predation toward underage women. But he seems resistant to any grasp of the notion that his behavior was responsible for what happened to “Ren & Stimpy,” or to his career in general.

Needless to say, there’s a lot of archival material to draw on here, from peeks at the show’s well-documented creation to various promotions and influences. (Kirk Douglas at his most histrionic was evidently a great favorite among the animators looking for exaggerated character expressions on the continuum between rage and panic.) Key personnel are garrulous and colorful in reminiscence, not least Kricfalusi himself. It is lost on none of them that their bratty broadcast baby opened the door to virtually all boundary-stretching, “Adult Swim”-type cartooning since.

. Notably, the titular song that was “Ren & Stimpy’s” single most viral (albeit pre-internet) sensation is never heard here. All excerpts from the show are presented in slightly altered ways (on an on-screen television, etc.), further suggesting some rights issues the film had to finesse around. As an overall package, however, it’s appropriately slick and punchy.