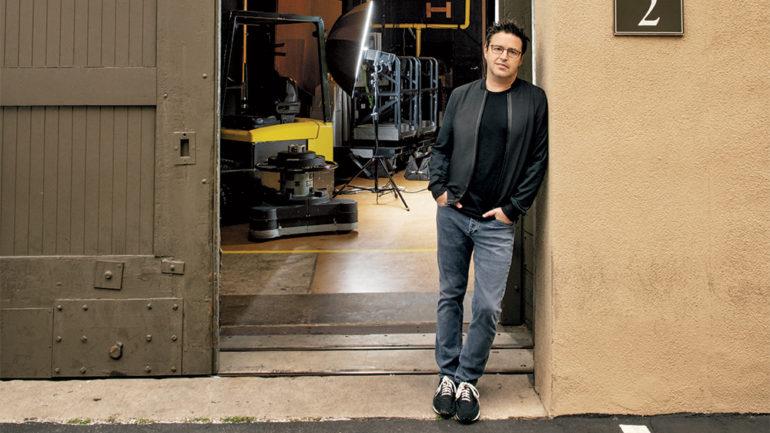

‘Ellen’ Producer Andy Lassner Speaks Out About Past Addiction Struggles to Inspire Others to Get Sober

By Cynthia Littleton

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – In Variety‘s Recovery Issue, prominent entertainment figures offer insights on navigating a sober life in Hollywood. For more, click here .

Andy Lassner has been candid on Twitter and other social media platforms about how low he sank in the 1990s as his addiction to heroin, alcohol and other drugs spiraled out of control.

“I’m someone who hit bottom and then furnished it,” says “The Ellen DeGeneres Show” exec producer during a lengthy interview. “I hung out there awhile.”

In early 1999, as he started his second stint in rehab inside of three months, Lassner took an accounting of his life and decided that death wasn’t a bad option. He believed he’d lost everything — his first marriage, his relationship with his oldest child, his job as a creative executive at King World Prods. He also believed he would never be able to control his urge to drink and do drugs.

“I had that moment of clarity that I wish on every addict. It was that moment of clarity where your brain goes, ‘Either you’re going to die, or you’re going to make your life better, and this is the turning point,’” he says. “In that moment, I made the decision ‘I’m going to live.’”

Lassner, 52, grew up in an Orthodox Jewish home on New York’s Upper East Side. It was a loving and stable family.

“I did not have a crazy childhood,” he says. “I didn’t come from abuse or a rage-fueled home. When people ask ‘What caused you to become an addict,’ the answer is that it’s just how I reacted to the world. It’s how I was born.”

He did battle anxiety and depression from a young age. As a preteen, his world changed when he was offered a cup of wine at synagogue after a service.

“I drank it and went ‘Wow.’ Suddenly I felt like other people. Suddenly I’m calm; I don’t feel so ugly or so short. Everything became OK,” Lassner recalls. “That triggered in my brain that this is something that makes me feel good.”

Lassner’s drinking during trips to synagogue progressed to the supply of whiskey and bourbon that he found in a refrigerator there. By the time he graduated from high school, he was an alcoholic and practiced at hiding it.

Lassner moved on to New York University, where he got his first taste of working in television production through an internship on the raucous daytime talk show hosted by Morton Downey Jr. He also got his first exposure to cocaine and crack. Soon he was routinely scoring drugs in Washington Square Park at 2 a.m., then heading uptown on weekends to be with his family.

Lassner, like many in recovery, emphasizes that the sense of shame and the urge to keep the depth of his problem a secret were exhausting and demoralizing.

“You will go to any length to have everyone think you’re normal,” Lassner says, “because you know it’s not good that you have a problem, and if it gets out, everybody will start hounding you about it. I thought that alcohol and drugs were my only true friends. They made me feel better, and they didn’t judge me. It turns out, people weren’t judging me all the time, but as an addict you sometimes feel very self-obsessed.”

Lassner eventually dropped out of college. His career in TV blossomed and his addiction worsened. One day while flipping channels, he came across the 1989 TV movie “My Name Is Bill W.,” starring James Woods as the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous. “It changed my life,” Lassner says.

At the age of 20, Lassner got sober. He attended 12-step meetings regularly for more than four years. He got married and became a father. He was tapped as supervising producer to help launch “The Rosie O’Donnell Show” in 1996. After about six years of sobriety, Lassner stopped going to regular meetings. He was working on a hit show and living a comfortable domestic life. “I felt that I didn’t want to keep talking about addiction,” he says. “I felt, ‘I’m done.’”

Early in the first season of “Rosie O’Donnell,” the host was named one of the “least kissable” celebrities by the makers of Scope mouthwash in a poll. It proved an epic PR blunder as O’Donnell mocked Scope for weeks on her show. Scope rival Listerine pounced on the opportunity and began sending cases of its mouthwash to the show.

Lassner took a look at one of the yellow Listerine bottles and noticed that it had a high alcohol content. Then he took a box home. “I wasn’t thinking, ‘I’m relapsing’ — it was just my brain telling me to gulp this,” he recalls. “It’d been so long since I’d talked about being an addict that my brain got in the way. I’m living a normal life, and still my brain is telling me, ‘Why don’t you try swallowing a little Listerine because no one will smell it on you.’”

In no time, Lassner was drinking half a gallon of Listerine a day. Cocaine, heroin and Vicodin soon followed. “After eight years of being sober, within a year, I’m 10 times worse than I ever was,” he says. “I’m grateful every day that I didn’t die of an overdose.”

At one of his lowest points, Lassner took his baby daughter, Erin, in a cab in the middle of the night to score drugs while his wife was out of town. He left Erin in the cab and told the driver to keep the meter running while he went inside a brownstone in Washington Heights to get high. He still doesn’t know how much time passed. He does remember the feeling of relief when he came out and saw the cab was still there. As the driver dropped them back at Lassner’s apartment, he looked at him with a mix of disgust and empathy. “I could have called the police. You need to get help,” Lassner recalls the driver telling him.

After two seasons on “Rosie O’Donnell,” Lassner moved his family to Los Angeles and took a senior VP post at King World Prods. “I thought, ‘Drugs aren’t my problem. New York is my problem,’” he says. “I thought I would come out to L.A. and clean up and fix my marriage.”

Within six weeks of starting at King World, Lassner was in such bad shape he was sent to rehab. He marvels at how generous the company was to a brand-new employee. King World connected Lassner with Dallas Taylor, the late musician who became known for his work with addicts.

“God bless the King brothers,” Lassner says of the late King World chiefs Roger King and Michael King. Taylor flew with Lassner to an Arizona rehab facility, where he eventually had the epiphany that allowed him to get healthy.

“I told myself that I was just going to shut up and listen to someone else for a change. Just for one day,” he says.

After his weeks in Arizona, Lassner lived for a year in a sober home with eight other addicts. “I was there with a punk rocker and a Stanford law student, and there we were, cleaning the bathrooms every day and living up to our commitments,” he says.

Lassner’s trials were no secret in the close-knit world of syndicated TV. But he was still getting offers to work, which proved to him that the entertainment industry “is a very forgiving business. If you’re good, you’ll work.”

Today, Lassner is happily married, to second wife Lorie, and is the father of three: Erin, now 23, and 12-year-old twins Ethan and Ryan. He gets a fair amount of screen time on “Ellen DeGeneres Show” as the host likes to draw him on camera for comedy bits and impromptu moments in the studio.

His longevity with DeGeneres is a rarity in TV. “Andy is an amazing producer because he has one of the quickest minds I’ve ever seen,” DeGeneres tells Variety. “What I admire most about Andy is that he has a very good sense of right and wrong. He is a decent person. He loves his family and friends and I know I can trust him with anything.”

She also affectionately notes that at times he has the “maturity level of a 10-year-old boy.” The trust between them is magnified by mutual respect and friendship.

“We make each other laugh every day,” DeGeneres says. “Andy is also not afraid to tell me when he disagrees with me.”

Given his history, Lassner feels an obligation to speak out about his experience as a means of offering hope to others. Because he is open about his addiction, he is frequently contacted by friends, co-workers and even strangers in need of help, as he was 20 years ago.

“I don’t spend my whole day going ‘Who can I help today,’ but over 20 years there have been people from every walk of life, from every aspect of my personal life and my business life who have come to me and said, ‘What do I do,’ ” he says.

Lassner’s interactions with fellow addicts help him stay vigilant about managing his own disease.

“Twenty years doesn’t matter,” he says. “I’m just sober today. I do feel a responsibility to talk about it and say to people, ‘You can do it. Don’t tell me about hopelessness. I get it. I was there with you.’ ”