David Lynch: The Conservative Heart of a Radical (Column)

By Owen Gleiberman

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – If David Lynch learned one thing from the uproar that greeted his original comments about Donald Trump (“Could go down as one of the greatest presidents in history because he has disrupted the thing so much”), which were made during an interview with the British newspaper the Guardian, it is this: In the internet age, what you say can and will be used against you. I have no doubt that whatever the public outcry against Lynch’s words, you could multiply it by a million — I mean it, a million — to register the gale force with which he was hit by it personally. That’s the way social media works, especially when you’re famous. For him, it must have been like standing in a hurricane.

The reason for the outcry, of course, is that , in the eyes of so many of us, stands for values — he’s an artist, he’s a humanist, he’s an explorer of the head and the heart (as well as darker squishier places) — that seem antithetical to the values of . The president is not a humanist. He has never displayed the slightest interest in art, unless you count his merde-gold Manhattan buildings (when have you ever heard him praise even a popcorn film or TV show that he wasn’t involved with?). And he appears to be the last person on earth who would want to explore anything about his own head or heart.

The day after the protest hit the fan, Lynch, who must have been reeling, walked back his comments in an open letter to Donald Trump on Facebook (“You are causing suffering and division”), which seems to have calmed the waters. Yet for those of us who consider ourselves devotees of David Lynch, a question still lingers: Why did he first say what he did? I don’t voice that question in the spirit of a “social justice warrior” who’s still asking for Lynch’s hide for something that he’s apologized for. I say it in the spirit of honestly wanting to know. Because I don’t think it was just a “mistake.”

I think the answer starts here. David Lynch, though one of the most radical film artists of our time, has always been a highly fluky and provocative sort of ironic cultural conservative. This first came to light around the time of “Blue Velvet,” which was released in the fall of 1986 and created, for the first time, a white-hot spotlight around Lynch.

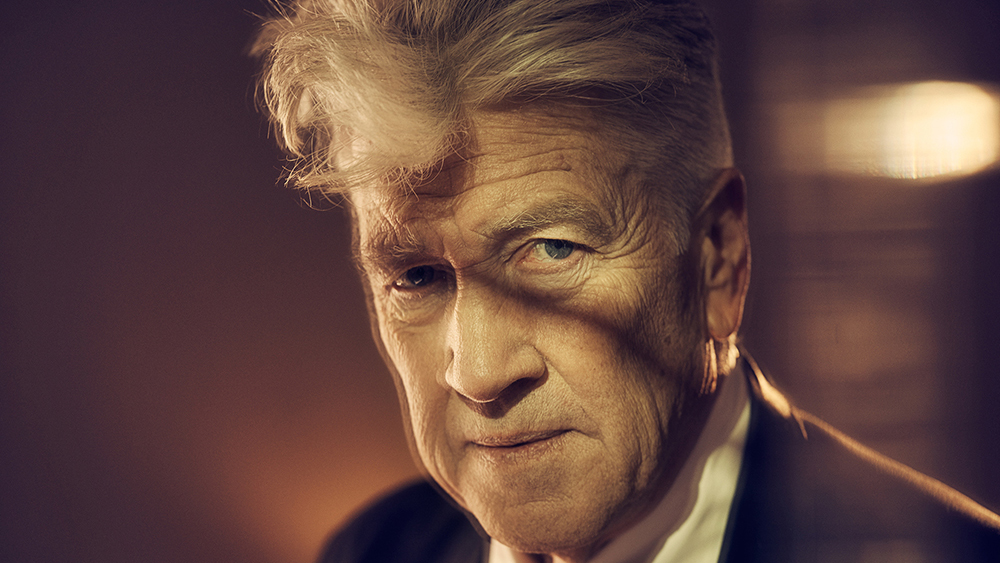

He’d received attention for “The Elephant Man” (1980) and “Dune” (1984), not to mention his visionary surrealist first feature, “Eraserhead” (1977), but it was during the season of “” that Lynch, in all his resplendent downtown idiosyncrasy, became an iconic figure: the white shirts buttoned up to his Adam’s apple, the smiling handsomeness set off by a shock of brown hair that made him look like Eraserhead crossed with an older echo of the star of “Blue Velvet,” Kyle MacLachlan, and, most strikingly, the way he talked — the wholesome jovial singsong voice and ironically unironic use of phrases like “Gee!” and “You betcha!” As so many people have noted, in one way or another, he came off like Jimmy Stewart hosting “The Howdy Doody Show.”

The crowning touch of Lynch’s look and aura was what was up onscreen. This was, after all, the man who dreamed up “Blue Velvet,” which in 1986 felt like one of the most authentically dangerous motion pictures ever made. It was a deep dark journey into fear and love and sex and kink and weird drugs and Pabst Blue Ribbon, and so the film’s very existence became the final accessory of the Lynch persona. It said: This aw-shucks boyish surface you’re seeing, this character, may be sincere, but it’s also an illusion. It’s as if the film was his confession, and to balance that out he crafted his image into something that was teasingly presentable.

But it was also the way Lynch had evolved. Born in Montana in 1946, he was a quintessential child of the ’50s, and he reveled in the Eisenhower era. He was attracted to its dark underbelly, to lifting up the rock and looking at whatever was under it, but for that reason — out of that very obsession — he fetishized the safety of the surface, the square American values he’d grown up with. The reason he never rebelled, except in his art, is that he thought it was that squareness that made his inner wildness possible.

I interviewed Lynch in New York during the press rollout for “Blue Velvet,” and there was a moment in our talk that was quite telling. I thought of him as a “free spirit,” and was asking him about the counterculture of the ’60s, to which he expressed a fairly marked aversion. “I didn’t like” — and he paused a moment before spitting out the word as if it were vile — “hippies.” He looked right at me, and since my hair was kind of longish at the time, and I had a lot of sympathy for the ’60s, I thought, in a moment of journalistic narcissism, that he was trying to make a comment about me. (I’d been asking him to explain his work, which I was already starting to realize he found irritating.) But then he told me, with a smile, that though he didn’t like the ’60s, “I’m starting to like the ’80s quite a bit.”

Lynch liked the ’80s because the decade reminded him, as it did so many people, of the ’50s. He was a big fan of Ronald Reagan’s; he grooved on the nostalgia, the feel-good boosterism. (I actually did too, even though I despised Reagan’s politics.) Lynch dug President Reagan for the same reason that he loved sitting in diners in L.A. drinking milkshakes and coffee: It made him feel that the ’50s of his youth was still going on, that Fortress America was still there to protect him. It was a feeling of intense security that gave way to creation. Flaubert famously said, “Be regular and orderly in your life like a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your work.” That was — and is — David Lynch.

I believe that Lynch thinks of everything, even American presidents, in aestheticized terms. In “Blue Velvet,” the sinful damaged S&M freak Dorothy Valens lived on Lincoln Street and was subjected to the torments of Frank Booth — a name game that was Lynch’s way of saying Frank was assassinating her soul. I think that Reagan, for Lynch, was a metaphor (for his own desire to travel back to the future), and maybe Donald Trump is too. Trump is a metaphor for just about everyone, including his supporters. With his pompadour and twisted lips, he’s the aging Elvis reborn as a political rebel — a rock ‘n’ roller of heartlessness. Lynch must think that he’s wild at heart.

But it is, of course, an act of supreme indulgence to treat political figures as metaphors when their actions have such powerful consequences. We’re living in an age where a great many Americans, from Trump on down, are starting to act almost proud of their indifference to human suffering, and David Lynch, when he made his original comment about Trump (voicing the most conventional defense of him there is: that he’ll “disrupt” the status quo), was speaking from a place of wealth and fame. It was right that he got slapped down, but the place he got slapped down to was the real world. And the grand irony of David Lynch’s conservatism is that what it expresses is that the real world is the last place on earth where he wants to live.