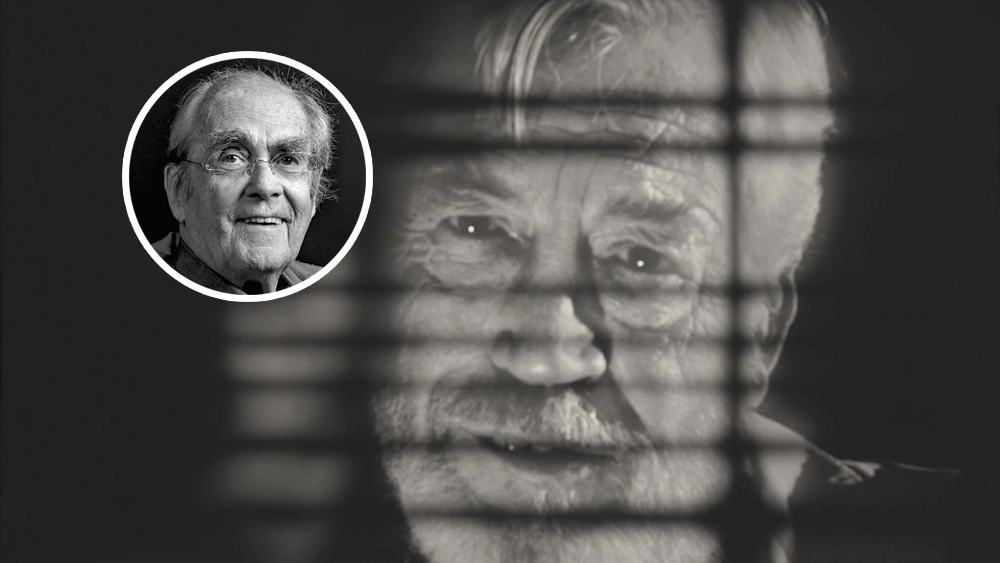

Composer Michel Legrand Sent Himself Back to ’70s to Work With Orson Welles on ‘Wind’

By Jon Burlingame

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – If a director and composer have success on their first film together, they typically work together again. But it is unprecedented for a composer to score that second project 40 years after the film is shot… and 30-plus years after the director’s death.

That’s what happened with French composer Michel Legrand, who — 44 years after completing the music for Orson Welles’ “F for Fake” — has now written the music for Welles’ long-awaited, finally completed 1970s film “,” which Netflix is releasing Friday.

“I loved Orson,” the composer, 86, tells Variety by phone from Paris. “I worked with him for almost a year on ‘F for Fake,’ and then he told me he was starting another one. I didn’t hear about that movie for 40 years.” Upon very, very belatedly getting the gig, “I asked myself constantly, ‘How would Orson have reacted?’ The very subject of the film touched me: the idea of the passage of time, the renewal of inspiration. I am proud to be the link between these two Welles films. I take it as a gift from Orson, through the clouds.”

Giving back to Welles with an epic score became such a punishing task for Legrand that the three-time Oscar winner (“The Windmills of Your Mind,” “Summer of ’42,” “Yentl”) barely survived the ordeal, literally.

“The Other Side of the Wind,” Welles’ legendary unfinished film, stars two famous directors (John Huston and Peter Bogdanovich) who play two fictional directors, an old lion and his successful modern protégé. Most of the film takes place at a California party where scenes from the elder director’s new film are screened before a crowd of young, camera-wielding acolytes. Welles’ film spent decades in legal limbo until producers Filip Jan Rymsza and Frank Marshall acquired the rights, found all the footage, shipped it to L.A. and assembled it into a work that will have cineastes debating its meaning and merits well into the next decade.

Welles’ annotated script contained notes that “made mention of a jazz score,” says Rymsza, including various kinds of music at the party. “We realized this could really use a dramatic score, too, especially the film within the film.”

Since Legrand had long ago hoped to score “Wind,” he enthusiastically accepted, and then spent the first two months of 2018 creating a complex tapestry that would encompass every aspect of the film: music for the party, music for the film within the film, and dramatic music for the film itself.

Everything about “Wind” was unconventional, and the music was no exception, producer Rymsza recalls. “Michel was so passionate about this project,” he says. “He broke the film down into chapters,” like a novel, “and then he wrote nearly two hours of music, wall-to-wall.”

Legrand describes his score as “somewhere between a fugue, a swing-jazz trio, the influence of the Second Viennese School [such 20th-century modernists as Arnold Schoenberg] and a piano duo where one is jazz and the other classical.”

Stylistically, the two Legrand scores for Welles are similar: Both “F for Fake” and “Wind” contain jazz and classical elements.

What’s different about “Wind” is the untitled, ambiguous film within the film, which features a mostly naked Oja Kodar (Welles’ companion and co-screenwriter) being pursued by a young man (Bob Random) in an Antonioni-esque cat-and-mouse game on various locations. Legrand’s music is “very dissonant, a combination of piano and dramatic percussion,” says editor Bob Murawski; “avant-garde and weird the way the film is avant-garde and weird,” adds Rymsza.

Legrand finished composing just before recording was to begin in mid-March. Then he collapsed and was hospitalized with pneumonia. “He was in critical condition,” Rymsza recalls. Two days of recording orchestra in Belgium, then two more days of recording a big band and jazz trio in Paris, went on without him. Luckily, Legrand recovered a month later, albeit too late to participate in the mixing or dubbing processes.

During the composer’s hospitalization and recovery, editor Murawski and music editor Ellen Segal raced to try and fit Legrand’s ambitious score to the film (they were scrambling to make the deadline for a Cannes screening, later cancelled when the festival barred Netflix entries). “Unfortunately, the idea of this wall-to-wall music that played through everything was too different to entertain,” Murawski concedes.

But 45 minutes of his music remains in the film, including considerable jazz, all of the avant-garde material and some of the more traditional scoring. Most unexpected of all is the melancholy Legrand piece that plays under Bogdanovich’s opening narration: It’s “Les delinquants” from the 1959 film “L’Amerique Insolite” by French director Francois Reichenbach –the director whose unfinished documentary on art forgery Welles turned into “F for Fake.”

The soundtrack album is expected to feature more of Legrand’s music. And Murawski and Segal speak wistfully about letting the entire Legrand score see the light of day via a Blu-Ray alternate version of the film.

So Welles and Legrand are reunited on screen one last time. “He brought a uniqueness that a younger composer would not have,” says Segal. “It had his jazz sensibilities, and his sense of drama and emotion,” adds Murawski. Says Rymsza: “We wanted a ’70s score and in many respects that’s exactly what we got. Knowing Orson, knowing the period, he was being true to Orson, and true to the film.”