Bertrand Tavernier Launches New Effort Restoring French Film Scores

By Ben Croll

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – PARIS — A True Renaissance Man of French cinema, director, historian and film preservationist Bertrand Tavernier can now claim another title – maestro.

For the past several months, the filmmaker has been working on a project honoring several pioneering French composers, restoring several pieces and putting together a program that he presents on Saturday January 19 in conjunction with UniFrance’s Rendez-Vous With French Cinema.

To be held in Paris’ Maison de la Radio, the concert, called “May the Music Begin!” will pay tribute to several classic French films and their composers. As an added lure, the show will premiere three restorations of scores never before played in concert.

The director sat down with Variety to explain both his process and goals on this new venture.

What are the roots of this project?

This project sprung from my passion for music and from the two documentaries that I made, the feature film “My Journey Through French Cinema” and the eight-episode series [of the same name] that screened on French TV last year, which was bought by the Cohen Media Group for the U.S.. Both the series and the film reserved a certain place for French composers. I principally focused on something specific to French cinema, which is the enormous number of songs written by film directors, from the 1930s, with René Clair and Sacha Guitry, all the way to the French New Wave, with Agnès Varda and Jacques Demy. I had never seen that focused on before; it wasn’t well known that Jean Renoir and Julien Duvivier wrote songs, many of which were very beautiful and moving.

Unfortunately, French composers also shared something else in common: Their works were nearly impossible to track down. There was a kind of ignorance or even contempt for their work for many years. Unlike in America, the producers did not finance the films’ scores. Instead, the music editors had to cover that expense. When I made my first film I had zero budget for music. The editors paid for the score, and in return received 50% of the music rights. With that 50% came the obligation to keep the music readily accessible, only that duty was reneged on and forgotten over time. And as a result, you couldn’t play some of the most celebrated film scores, whereas in the U.S., orchestras mount works from Korngold, Bernard Herrmann, and Max Steiner right from the beginning. Growing up, I could buy the scores for “King Kong” and “Citizen Kane” but it was impossible to find “La Grande Illusion.” Nobody thought to record the most celebrated score from the most celebrated film!

So how did the project come into being?

For ten years I’ve been saying how scandalous is it that some of French cinema’s greatest music was out of reach. American conductors took film music seriously, and they would add them to their repertoires very early on. In France, “serious” musicians viewed film music as frivolous, forgetting how many real talents contributed to the form. And so this project was born of the need to rectify that.

I’ve been working on it for months, making the selections, taking meetings, negotiating with musicians, tracking down the music, ironing out tricky copyright issues, and even getting into fights.

It all clicked when I figured something out: The rights-holders were obligated by law to offer the musical pieces continued distribution. They weren’t doing so, but that didn’t stop them from collecting their initial 50%. But French law is strict when it comes to authors’ rights, it was on our side, so we were able to work things out in our favor. It wasn’t even the fault of the current rights holders. Many are conglomerates that have been bought and sold several times over the years, and they had no idea what they held.

[I did it all because] I wanted to help others discover the variety of French of composers, from [“L’Atalante” composer] Maurice Jaubert, whom I esteem as the greatest of his age, all the way to Georges Delerue [“Contempt”] and Antoine Duhamel [“Pierrot le fou”], and I wanted to honor music that had never received treatment before.

You’ll be premiering three recently completed restorations. What can you tell us about those?

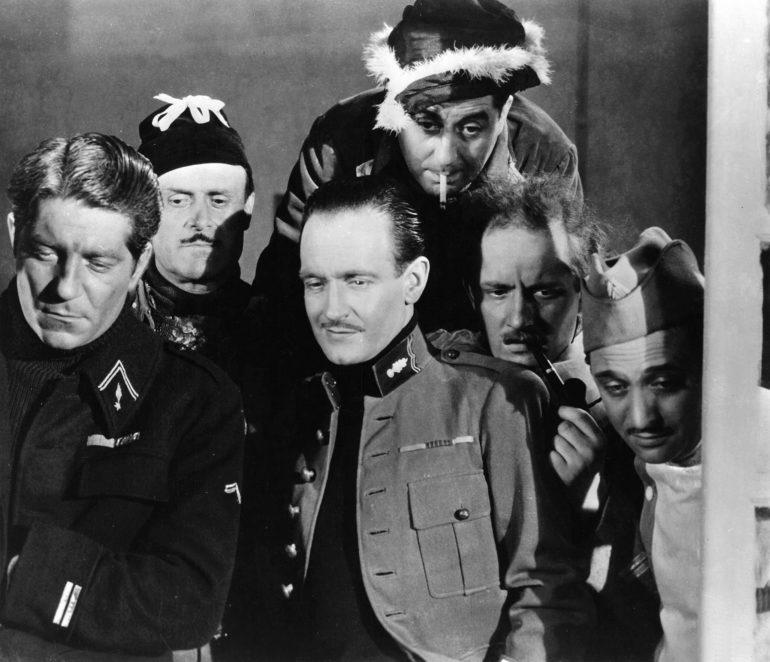

We’re going to finally present Joseph Kosma’s score for “La Grande Illusion.” [Musician and conductor] Bruno Fontaine reconstructed that score from the DVD. He watched the film again and again in order to rewrite the sheet music. He did a similar thing for “Mr. Arkadin.” In that case, composer Paul Misraki wrote the music before Orson Welles even shot the film. Welles described the story to Misraki for two or three hours, and then told the composer to go write a score. And Misraki wrote an incredible piece of music that is simply not findable – the only place it exists is on the DVD. And together with Bruno Fontaine, [composer] Michel Legrand wrote a new arrangement for his “Sinners of Paris” score, which was one of the first big-band jazz scores in French cinema, and another one that was never properly recorded.

Indeed, you hold Kosma in high regard.

I would rank him among the best. On top of his “La Grande Illusion” music, we’ll also play one of the suites from “Children of Paradise” that he composed under very difficult circumstances. A communist and a Jew, he had to go into hiding during the war. He wrote that score while on the run, and then had to deposit his work with a music publisher based in Switzerland. Honestly, I would have loved to focus entirely on Kosma’s work with Renoir, because the composer also did “La Bête Humaine,” “A Day in the Country” and many other pre-war films. I could have devoted 40 minutes to Kosma alone.

What other pieces are you excited to present?

Jean-Jacques Grunenwald’s work on “The Truth About Bebe Donge” was for a long time one of my all time favorite scores. For me, that music is like Philip Glass, only twenty years earlier. The music has a repetitive quality; it’s an ostinato for piano, organ and small bit of strings that repeats the same motif, and nobody else was doing that in the early 1950s! Nobody else was doing that until Glass came along two decades later. I have as much admiration for the composer as for his work, and so I want to pay tribute to them both. [It wasn’t easy, because] Warner/Chappell, who held the rights, never published any sheet music. Instead we had to reconstruct the music from the DVD, filling in the blanks for moments when dialogue and sound effects drowned out the score.

What are some of the differences between French and American scores from that classical period?

Toward the beginning of the sound era, music was used very sparingly, and that allowed those early films to age quite nicely. Later — and even up to today — movies would be inundated with music. Someone once said that certain films have 140 minutes of music for 120 minutes of screen time, and that certainly feels the case for many American films from that period.

Of course, French cinema was influenced by Ravel, Poulenc, and Debussy, but Berlin cabaret musicians from the 1920s also had a marked effect. Musicians like Kurt Weill and Hanns Eisler had a determining influence in French industry that was not the case in the Hollywood, where composers came from the Viennese school. In the 1940s and 50s, American composers were influenced by people like Brahms, Mahler, and Bruckner. In Hollywood, it was always big orchestras of more than 60 people, never something like the seven musician ensembles with nothing but trumpet, percussion and saxophone that Maurice Jaubert or Jacques Ibert would sometimes use. Nothing like that exists in classic American cinema.

Do you plan on organizing the concert in chronological or more thematic order?

I’m not entirely sure of the order. I think we’ll try to honor the timeline, but if two works are overly similar, we’ll try to space them out and mix things up. For instance, Bruno Fontaine wrote a beautiful arrangement that mixes “Contempt” and “Pierrot le fou,” a kind of Godard suite. The show will close with a piece that I never mentioned in any of my documentaries: Jean Françaix’s score for “Royal Affairs in Versailles.” I didn’t include that Sacha Guitry film in any of my docs because it had never been restored, and what’s more, it’s not one of my favorites. I prefer Guitry’s intimate comedies to his historical films, but Jean Françaix’s music is still tremendously beautiful. It concludes the film, and it will conclude the concert as well.

Is this a project you’d wish to pursue further?

Oh very much so. Someone from Radio France told me that if this works, we’ll have to do it again. I have a long list of things I’d like include. For instance, one day I hope to record what Martin Scorsese finds the most beautiful piece of music from French cinema: Paul Misraki’s score for “The Proud and the Beautiful.” For a scene where actress Michèle Morgan goes to a Mexican village to accompany her ailing husband, Misraki wrote this incredible piece where the local mariachi music interrupts and intermingles with his more modern score. I think it would have a spectacular effect if played in concert. Of course, we’d have to restore it first, because there’s no independent recording.