‘Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered’ Editor on Not Wanting to Leave Anyone Out

By Jazz Tangcay

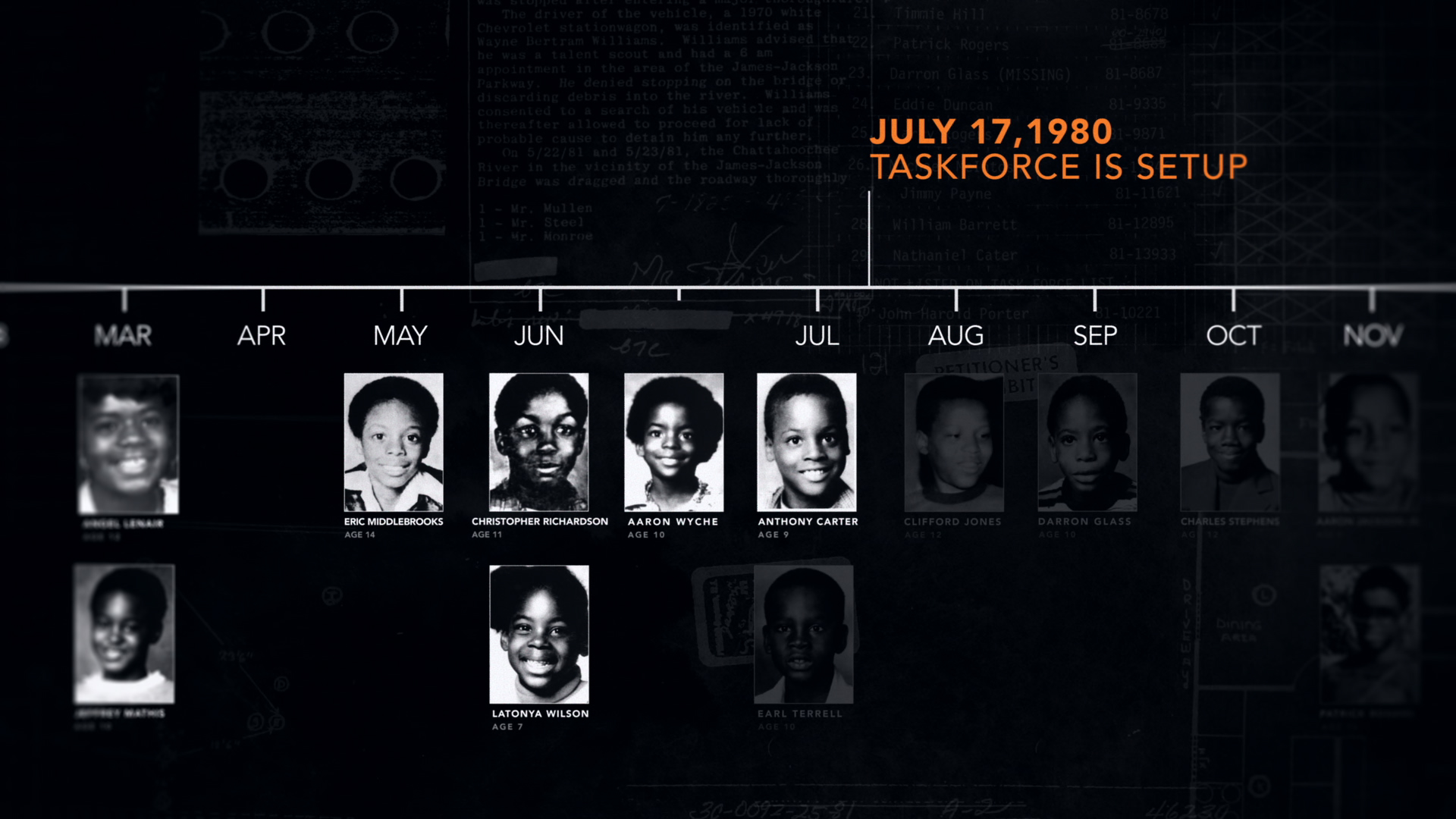

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – “Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered: The Lost Children” is a five-part series on HBO that dives into the crime spree that terrorized the African American community and saw 29 children murdered or kidnapped between 1979 to 1981. Through previously unseen heart-wrenching interviews with the victim’s families, law enforcement, journalists and footage of Wayne Williams (who was jailed for the crimes but maintains his innocence to this day), the docuseries sheds a new light on the devastating loss of lives, questions who really committed the crimes and examines the failure of the American justice system.

“We couldn’t leave anyone out,” says lead editor E. Donna Shepherd.

Shepherd worked alongside editors R.A. Fedde and Ed Barteski to weave together the emotional story that puts the victims’ faces front and center in the world. Although that is emotional for the families, the production team shared the docuseries with the families and “talked them through in detail what they were going to see,” says producer Saralena Weinfeld.

“We wanted them to be able to see what we’d created and allow them to respond to it in a way that felt private and safe,” she continues. “We’re grateful that the responses we got were so positive because their bravery is the heart of this story.”

Here, Shepherd talks with Variety about the important opening sequence of Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms reading the victim’s names and challenges with sifting through much more footage than could make the final cut.

What did you know about the murders and disappearances beforehand?

I honestly could not have told you anything about it when I started. I sometimes think that is a good thing as an editor because you then know what the audience needs to know.

How did you approach the editing for this with all the complex layers involved?

It was intensely difficult to grasp all the moving parts. When I started putting things together, we knew that there was a possibility of telling the story out of chronological order but we had to start with chronological order. Once we had that, then we could start asking, “Should this move somewhere else?”

The first two things that I cut were the open and then the Bowen Homes explosion [the ending sequence for Episode 1]. The Bowen Homes explosion gave us a place to go — and a framing for the tone of the series.

Episode 2 was five hours long at one point after I had cut all the scenes that needed to go in. We [also] had so much story that needed to go in if Episode 3 was going to be the trial. I ended up cutting the sequence in half and just worked on it as 2 parts.

The sequence of Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms reading the names of the victims is powerful. How did you land on that start?

That was Saralena’s idea. Originally, I think we were thinking that it would go at the end of Episode 1. It was one of those sequences that we knew was important but we weren’t exactly sure where the most powerful place for it would be. For me, its importance lies in its ability to tell you the lens through which we are telling the story very succinctly and powerfully.

What about the recurring theme of the coffins?

[One of the victim’s mothers] Sheila Baltazar says it all when she says that she wanted to leave the casket open so that people would know that this could have been anyone’s child. She wants this thing that happened to have meaning, to be important, for people to care. She knows that press will be there and so this hearkens back to Emmett Till and his casket being left open so that it’s not hidden away.

The key factor to through the series is every child is known — they’re not a number or a face.

The way the interviews are directed is critical. The editing choices of when to be on camera for those interviews I think can make a real difference in how you feel about what the interviewee is saying. Bob Buffington is one of my favorite characters, editing-wise, in the first two episodes because he shows you all of his emotions right there on his face. You feel the pain through his pain and so you linger on him a little.