Aretha Franklin’s Producer Narada Michael Walden Remembers the Queen of Soul: ‘Her Eyes Had That Fire’

By Jem Aswad

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – In the mid-1980s, Aretha Franklin’s career was at a low ebb. Not only had her long hot string of hits largely cooled off, her beloved father, the Reverend C.L. Franklin , had died after spending years in a coma.

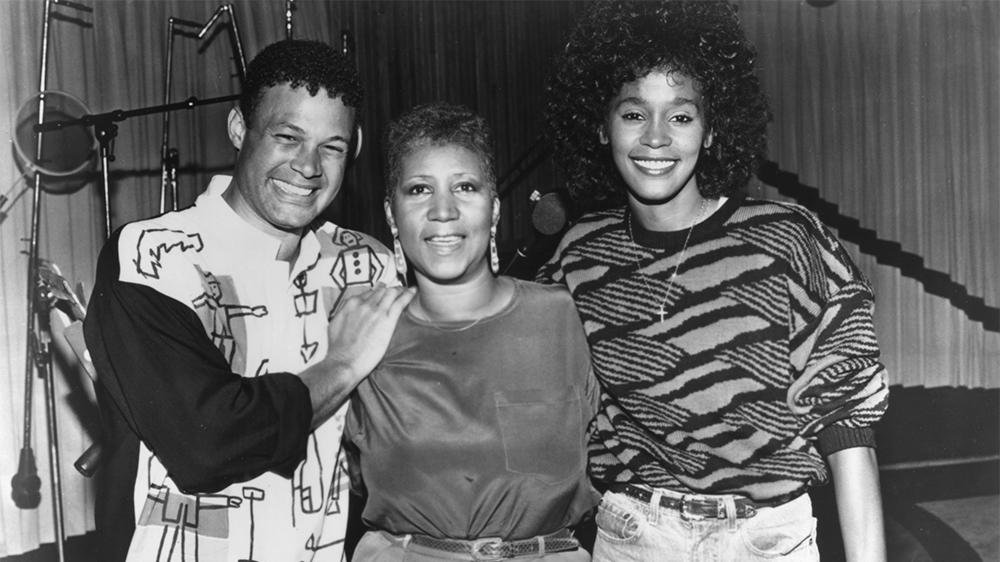

During this time, she joined forces with producer and songwriter Narada Michael Walden, a young jazz drummer who over the years worked with Whitney Houston, Mariah Carey, Diana Ross, Ray Charles, Stevie Wonder, George Benson, and many others. The resulting album, “Who’s Zoomin’ Who,” updated Aretha’s sound and reignited her career, producing the hits “Freeway of Love” and the title track. Walden (pictured above with Franklin, center, and Houston) would go on to oversee four albums and many songs for Franklin — including the No. 1 duet with George Michael, “I Knew You Were Waiting (For Me)” — and contribute to even more, notably an unfinished album she was working on up to the time of her death.

Variety spoke with Walden on Thursday, just hours after Franklin’s death was announced, about their work together, their friendship, and the pressure and pleasures of working with the Queen of Soul.

Until recently, the two of you were working on songs for her next album?

Yes, we were going back and forth a lot on text, she would tell me exactly what kinds of songs she wanted, I’d write it and demo it and send it to her, she’d write me another text ask to request another direction for a song, I’d write another one. But I’d been playing drums with her for the past two years and of course the last show I played with her was her last show, at the [Elton John AIDS Foundation Gala] in November .

I was at that show — she was very thin but she sounded great.

It was an incredible show: She sang hits, she played piano and she sang “Nessun Dorma” [the opera song she sang at the 1998 Grammy Awards, filling in at the last minute for Luciano Pavarotti]. When people first saw her they said, “Woah, she’s lost so much weight,” but then she brought so much attention with her singing that it was all good. Sting told me he cried when she sang “Nessun Dorma.” It was powerful!

| : Her Life and Career in Photos |

Do you know how much progress has been made on the album she was working on at the time of her death?

I don’t, all I know is I’ve been writing songs for her over the past couple of years, over 20 songs. It’s funny though, after all those successes [with albums and singles], we’d never played live together until the past two years, and that’s when I realized we had a whole new love for each other playing onstage. The first time I played with her we kicked ass, and then she wrapped up her throat in a wet towel like a prizefighter and sat there starin’ at me! And from then on she kept asking me to come back and play with her because she wanted me to do what I do, which is stomp it, y’know? But there was tender stuff too, like when she played the piano — people don’t understand that, it’s a whole other thing that she was a genius at.

Your albums with her in the ‘80s revived her career, both commercially and creatively. There must have been a lot of pressure when you first started?

There was so much on me, not in a bad way but in myself. I knew it was my chance to go to outer space, so much that when I got a call to do a session I passed — “I can’t work with anybody right now, I’m doing my first album with Aretha.” And [Houston’s A&R exec] Gerry Griffith, who I loved, said, “You don’t want to pass on this thing I’m bringing for Whitney, I want you to rewrite it, don’t sleep on it,” and I said “Okay, send me the song.” So in the same session that I did “Freeway of Love” and “Who’s Zoomin’ Who,” I also did [Houston’s No. 1 hit] “How Will I Know.”

Anyway, in doing those sessions, Aretha hadn’t been singing for two years, because her father had been in a coma. The first two songs we did were “Until You Say You Love Me” and “Who’s Zoomin’ Who.” In the studio, she was so tender from not singing, but she would bring it, man. I’d send her a copy of the song, she would learn it, and every time she would know what she wanted to bring to it. And that was a joy — most singers come in not knowing what they want to sing, sometimes not even knowing the song. But she knew every little thing she wanted to do, to the point where she wouldn’t want to do more than three or four or five takes.

Like, once there was one part I thought was too bluesy for a pop song, and I said “Can I get one more take?” “Well … why?” I said, “Right here, I think we can make it a little more mass appeal.” “Well, play it to me.” I’d play it to her, and she had a cigarette with a long ash on it, and she looked at me: “Well, that’s just the way I hear it.” “I know you do, it was great.” She’d say, “Okay, I’ll be nice to you, I’ll give you a straight reading and sing more to the melody,” and she would. But inevitably, when I’d go back and [compare] all the [vocal takes], I’d end up picking what she first did, because it had so much gumption in it.

What was it like the first time you were in the studio with her?

She showed up in a big old fur coat and jeans, it was snowing out, and her hair looking really pretty, and she just stared at me. I was behind the console at United Sound [in Detroit], jamming music, getting ready for the session and she came to the sliding glass doors and just stood there, staring at me — hearing the music, but just staring at me. Her eyes had that fire — I don’t know if you ever met her, but she had a lot of fire in her eyes, so when you see her you realize that this person is even more than you think she is — she is for real! And then you bow down, and you stay down!

But when the music comes on, you’re on the same team, you’re both working to make a hit song together, and then everything is cool. Then she wants to order in food — “Norma, go down and get me my fried chicken!” — everything’s good and she’s singin’ hard and doing her thing, and she’s kind and loving and happy because now we’re making hits and she’s excited. There was no more of that she’s up there and I’m down here — now we’re on the same team. And from then on we were the best of friends.

So she was trying to psych you out at first?

It was a staredown! Like fighters having a staredown, like Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, but she knew I was just too sweet for all that. I wasn’t gonna fight with her, I wanted to make hit records. I came in like, “I’m gonna do something with you that’s gonna be great for all of us, but I’m gonna be humble and sweet and bring you teddy bears and flowers and talk to you nicely, and even if I don’t agree, I’m gonna find a way to bring light into it.” And that’s when we got along like honey and apples.

You did four albums with her as well as the songs for the album she was working on over the past couple of years — what’s your favorite song out of all of them?

The first song I ever did with her, “Until You Say You Love Me.” After meeting her, I brought this track with me that was inspired by the Prince track, “The Beautiful Ones,” which was kinda inspired by this song on my first album called “First Love.” I did my drum overdubs fast, so when you played it back slow it sounded heavy and ethereal, so I wanted to do that with her and give her a new sound. To hear that sound against her raw, pure, soul voice was like Daaaaammmnnn! I was just trying to get her to be as great a singer as she is: her timing, her pitch, her phrasing, how hard she studies, everything she brings — that’s we all want to do.

Had you ever heard her sing opera before she sang “Messun Dorma” on the Grammys in 1998?

I did! I went to her house one time and she played Pavarotti for me, she wanted me to sit down and listen to a piece she was going over. She told me at the time she wanted to record some Pavarotti, and this was way back in ’85.

Did she ever?

Not that I know of. She just really focused on “Nessum Dorma” and had it ready to go. And don’t forget, it was in Pavarotti’s key — they didn’t have time to change the key because he cancelled so quickly, so she sang it in his key.

You’ve worked with Whitney, Mariah Carey — was Aretha the greatest singer you’ve ever worked with?

You know what it is? We call her the Queen of Soul, and often she didn’t want me to call her that toward the end of her life, she’d say “Just call me Aretha, just call me Ree-Ree.” But I always called her Queen because she taught us all. All of the things she learned opening for Mahalia Jackson in the church when she was a little girl: How to put the church into a frenzy, how to put the human heart and soul and psyche [into a song], she knew how to do that better than anybody. And you match that with her vocal prowess and control and range — and that’s what makes her out of this world. That’s why Whitney could be Whitney — she learned from Aretha. Everybody did. Aretha’s task was no joke — Mahalia wouldn’t come out until the place was in a frenzy. I asked her, “How did you get to be like that?” She said, “I learned because I had to open for Mahalia.”

I remember the show we played before that last one, in Boston, she was in pain, and during one of the songs she got in this spirit thing about going to the doctors, she was telling this whole story and there was blues in it, and she started praising God, and it went on for half an hour! I’ve never done anything like that onstage — it was beyond the church, it was like a living communion, and the crowd just loved and trusted her so much and opened their hearts to her. She’d tell the story and “Praise the lord!” and “Hallelujah!” and all that, and she’d go “Heeeyyy!” and the backing singers would sing it back to her. And it was all from her spirit, spontaneously. That’s what I mean when I say just how genius she was. She was the real deal, brother.

Did you get to hang out much with her socially?

I would when I’d go out to Detroit. I’d ask, “We going to the studio today?” She’d say, “You see that snow comin’ down?” “Yes, Miss Franklin.” “We’re not drivin’ in that snow.” This would go on for three days! (laughter) So there was a lot of time to kill and we’d hang out, and the food was really good and all those type of things — she was very motherly. I went to her house a few times to go over songs, that was very cool, and I went for a big party she had, that was really cool. She was very family, family was everything.

Any particularly funny stories or memories?

It was more like having fun, especially when we’d talk on the phone. When I first called her, I said, “What do you do for fun?” She said, “Oh, I might go up to the nightclub and maybe I see a guy in the corner and he looks at me and I look at him and maybe it’s a who’s-zoomin’-who kinda thing. So then he thinks he got me, right? But then the fish jumped off the hook!” And she laughed and laughed. I was writing it all down. She talked in her own way, man: very hip, very creative.

So “Who’s Zoomin’ Who” was her phrase?

Yes, that’s why I credited her as a cowriter on the song.

Any other nice memories you’d like to share?

I’d bring her little gifts, like a doll or a little tape recorder or speaker or some cool thing, and she’d be so charmed. I was always trying to ingratiate myself with her because she worked hard and she came from poverty like I did, and she was older than me, but we connected. I could talk to her about almost anything and we’d be cool. Out of the friendship grew the love that made those hits. You can hear the love in the records.

RELATED VIDEO: