Ana Elena Tejera Talks About IFF Panama Opener ‘Panquiaco,’ Belonging, ‘Slow’ Cinema

By Martin Dale

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – Supported by the Tribeca Film Institute, winner of the IFF Panama’s Primera Mirada pix-in-post showcase and selected for Cannes Film Market last year before world premiering at January’s Rotterdam Film Festival, Ana Elena Tejera’s “Panquiaco” opened this year’s IFF Panama festival on Wednesday.

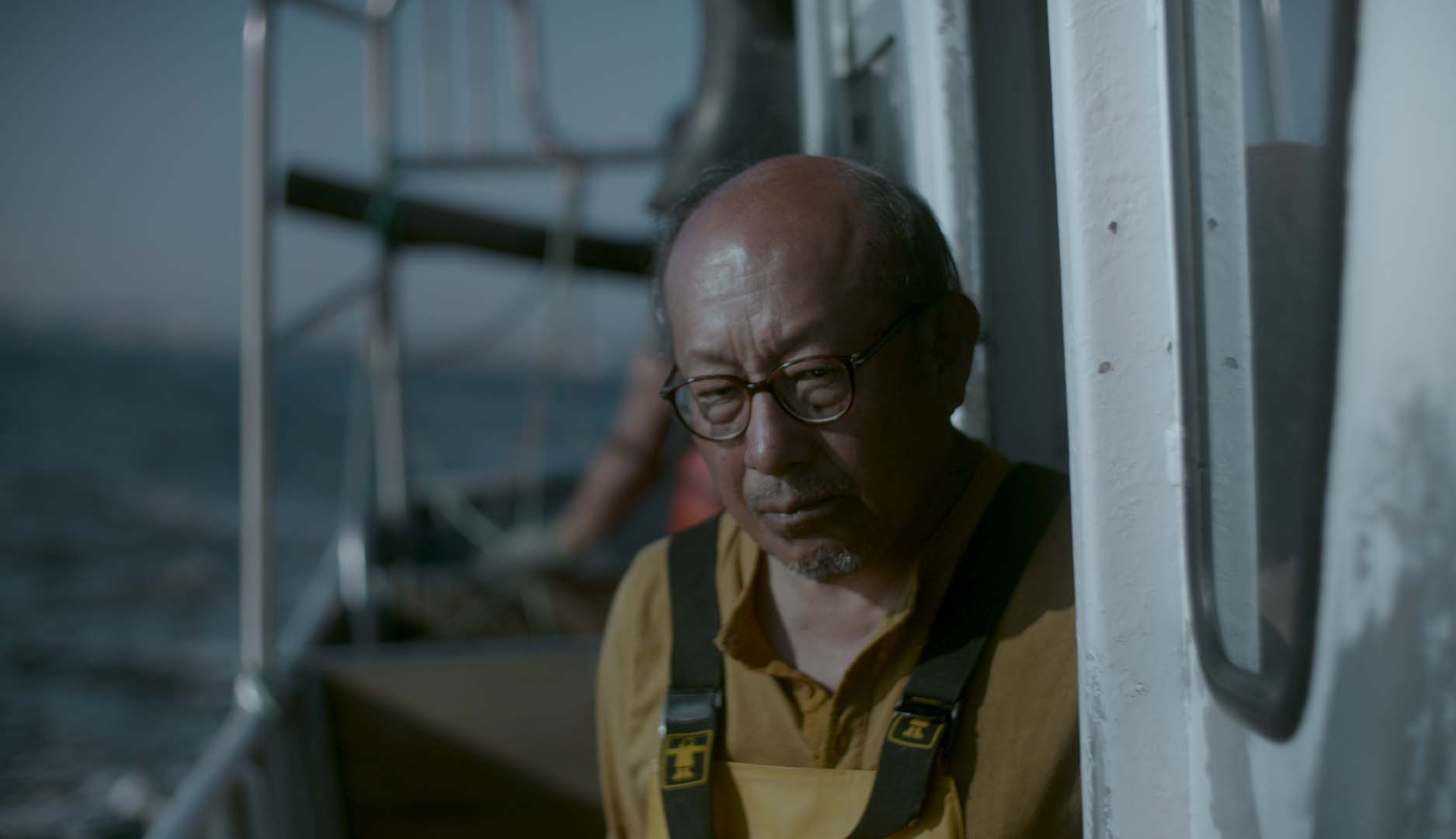

That marks further recognition for a hybrid documentary-fiction film which talks about belonging and plumbs community life in an indigenous village in Panama’s Guna Yala region, poetically tracking the journey of 67-year old Cebaldo, who lives in Portugal but returns to his village in Panama which he left as a young man.

The film also explores the link between his character and indigenous tribesman Panquiaco, who showed Spanish conquistador Vasco Nunez de Balboa a way from the Caribbean to the Pacific Ocean.

Produced by Tejera, Maria Isabel Burnes (Too Much Productions) and Tomas Cortés-Rosselot (Cine Animal), “Panquiaco” will also open Frames of Representation at London’s Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA).

Tejera is pursuing an artistic residency at Le Fresnoy in France. In April she returned to Panama for the IFF Panama Festival and has remained there due to the COVID-19 crisis. The pandemic also stymied an on-site edition of IFF Panama, which has been transformed into a five-day online festival, running May 22-26, including film screenings and round tables. Interviewed by Variety, Tejera talked about her inspirations for the film and her current project, a short film featuring her grandmother.

How has “Panquiaco” been received so far?

Obviously this is an exceptional year because of COVID-19. The reception at Rotterdam was wonderful, with full sessions and a good critical response. We have been invited to several other important festivals, including HotDocs, and we will be the opening film in Frames of Representation of the Institute of Contemporary Art in London. It is due to premiere in Portugal at the end of this year. It is great to be the opening film at IFF Panama.

“Panquiaco” has a very distinctive aesthetic approach, how would you describe it?

Since the movie’s premiere we have received comments about the new narrative style from Central America. I am not interested in using labels such as fiction, documentary or essay. My own background is linked to psychology, working as an actress and in performance art. I aim to make films that are more like performances. I’m interested in conflicts that are rooted in real-life contexts, but are then sensed through the body and lead to a transformative experience that is shared with the audience. I like what Marina Abramovich said about the difference between theatre and performance: “In theatre, the knife’s not real, the blood is not real. In performance it’s real.”

What have you learned from making “Panquiaco”?

It transformed me in a powerful way . I feel very involved in performance art, where I can work with my own subject matter, with my own conflicts and that’s how I feel that I work in cinema. Cinema helps me heal, remember and understand my relationship with myself and with my environment. Panquiaco, without being literal, speaks about my inner world, my conflict of belonging, that connects me with Cebaldo. We both have the same conflict, despite our differences in age and gender and Panquiaco was the way to do work through that in a performance. I learned from the indigenous peoples how to live in the present and have a relationship of respect with all living beings. This transformed me and made me think that belonging is more transcendental than an emotion of a single life or a single being. The community where we filmed has a powerful relationship with rocks, animals and plants. We filmed their rituals and tried to capture the feelings from the inside, not as ethnographic observers. I learned a lot from my cinematographer Mateo Guzmán who is from Colombia and who worked on César Acevedo’s [Cannes best first feature and Critics’ Week winner] “Land and Shade.” I’m also inspired by Portugal’s Pedro Costa.

Tell us a bit about your new project….

At my artistic residency in Fresnoy, I’m preparing a short film about my family, in particular my grandmother, who acts in the film. The entire film is conceived as a performance. I take the story of my grandmother, who grew up in the military dictatorship in Panama and effectively lived in a domestic dictatorship at home.

I was born in 1990, a few months after the end of the regime run by a military junta. In my country the dictatorship has been an unspoken and under-investigated subject, I only really began to understand the dictatorship through restoring film archives. At the same time I didn’t know about the story of my own family and my grandfather who was a soldier. Through the film I confronted my family’s past and how the influence of a country’s dictatorship could be dictatorship in a house. What I have learned from this new project is that we need more than one life to cure past suffering. It takes at least three generations to heal the scars of the dictatorship.

Has your view of Panama changed from making these projects?

My relationship with the country is changing all the time. Panama is a place that unites two waters, and at the same time separates them, the place that was divided by the U.S into a Canal Zone. Panama’s history is full of divisions, miscegenation and contradictions. Contradiction is everything, light and darkness, that’s why in my work I explore memory as something that is diffuse – living as a sensation that strengthens the soul and at the same time ceases to exist. This ephemeral and at the same time strong sensation, is a beautiful state of being, it is what makes us more vulnerable and I feel that it is Panama, pure vulnerability.

What was it like to have the online Panamanian premiere of your film at IFF Panama?

The online premiere in Panama, the country where Panquiaco was born, was an experience, it felt almost like Cebaldo’s conflict: a nostalgia for the past. In our case, we long for physical festivals where we can share with our community. Now things are different, we need to find new ways and forms to connect. However, within this contradiction I feel something beautiful. I have noticed that the quarantine has created a vulnerable environment for watching cinema. Now that we have slow lives, with time to reflect, I noticed that audiences are more open to this type of films. In our new reality, we can spend hours watching the water boil and give space and time to understand what happens in our internal world. Now life has been transformed into what is called “slow cinema”, “auteur cinema” and “experimental cinema” and this is very beautiful!