Leonardo da Vinci drawings go on display at Buckingham Palace

LONDON (Reuters) – Leonardo da Vinci’s thumbprint and preparatory sketches for some of his most famous works are going on display to the public at Buckingham Palace, in what is being billed as the biggest exhibition of the artist’s work in more than 65 years.

Marking 500 years since his death, “Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing”, which opens at The Queen’s Gallery on Friday, boasts more than 200 drawings by the Renaissance artist, taken from “the unrivalled holdings” in Britain’s Royal Collection.

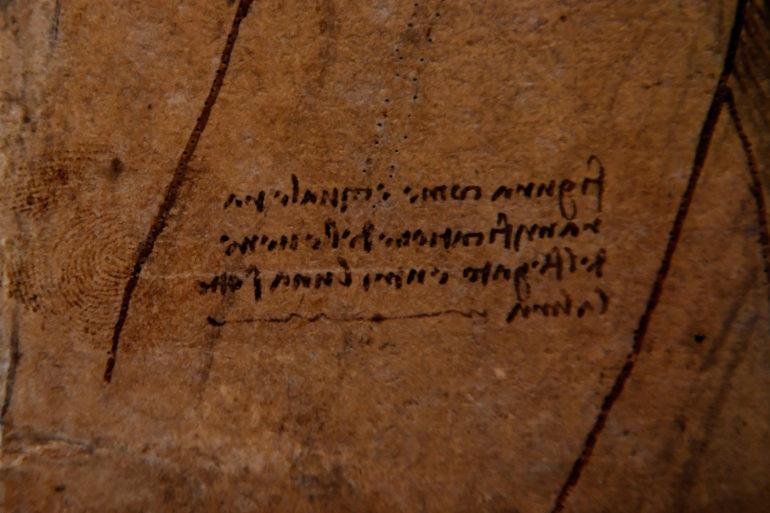

The drawings by da Vinci, acquired during the reign on Charles II, have been kept together since the artist’s death on May 2, 1519 in France’s Loire Valley.

“The drawings show that Leonardo was a serious practitioner of sculpture, architecture, engineering and a scientist in many different fields,” said Martin Clayton, exhibition curator and head of Prints and Drawings at Royal Collection Trust.

“He saw himself as a fully rounded figure, but drawing is the activity that pulls it all together.”

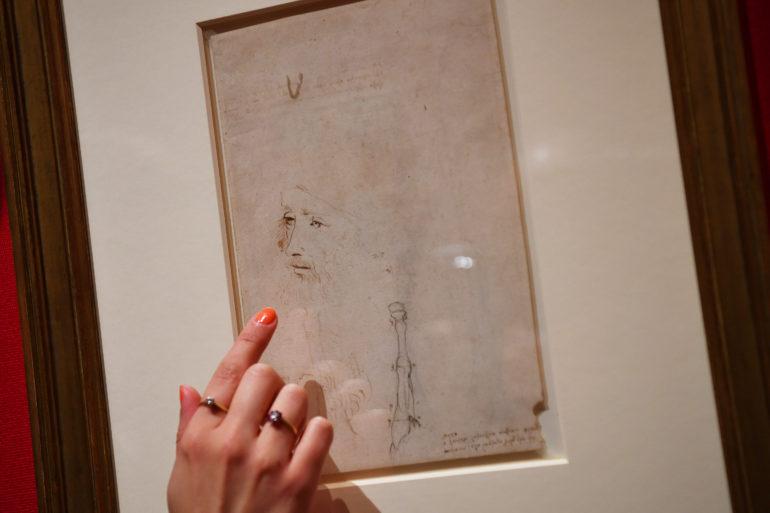

Highlights include the only two surviving portraits of da Vinci drawn during his lifetime, including one by an assistant that was previously unseen by the public.

“This drawing shows a certain wistfulness I think, a certain melancholy even,” Clayton said. “It’s not Leonardo, the great philosopher gazing into the distance. It’s a flesh and blood man at the end of a career that had achieved a great deal, but also maybe failed to achieve a great deal as well.”

There are also preparatory sketches for his works “The Last Supper” and “Salvator Mundi”, a portrait of Christ which became the most expensive painting sold at auction when it went for a record $450 million in 2017.

Other items include “Leonardo’s studies of hands for Adoration of the Magi”, which appears to be drawn on a blank sheet but, under ultraviolet light, reveal other “disappeared” drawings.

His anatomical studies are also on display, including one that Clayton said “was used by him to prepare his artistic projects, but also to conduct his scientific investigations.”

“Leonardo knew that these drawings at the end of his life were the only real record of what he had worked on and what he had achieved, and so if you want to understand Leonardo in the round, drawing is the only way that you can do that,” Clayton said. “This exhibition gives visitors a full picture of Leonardo.”

(Reporting by Lisa Keddie; Writing by Marie-Louise Gumuchian; Editing by Edmund Blair)