Disgraced Donkey Kong Champ Billy Mitchell’s Redemption is a Sloppy Soliloquy

By Jon Irwin

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) –

“I was told not to do this.”

– , Saturday, June 9th, 2018

Billy Mitchell is the best at what he does.

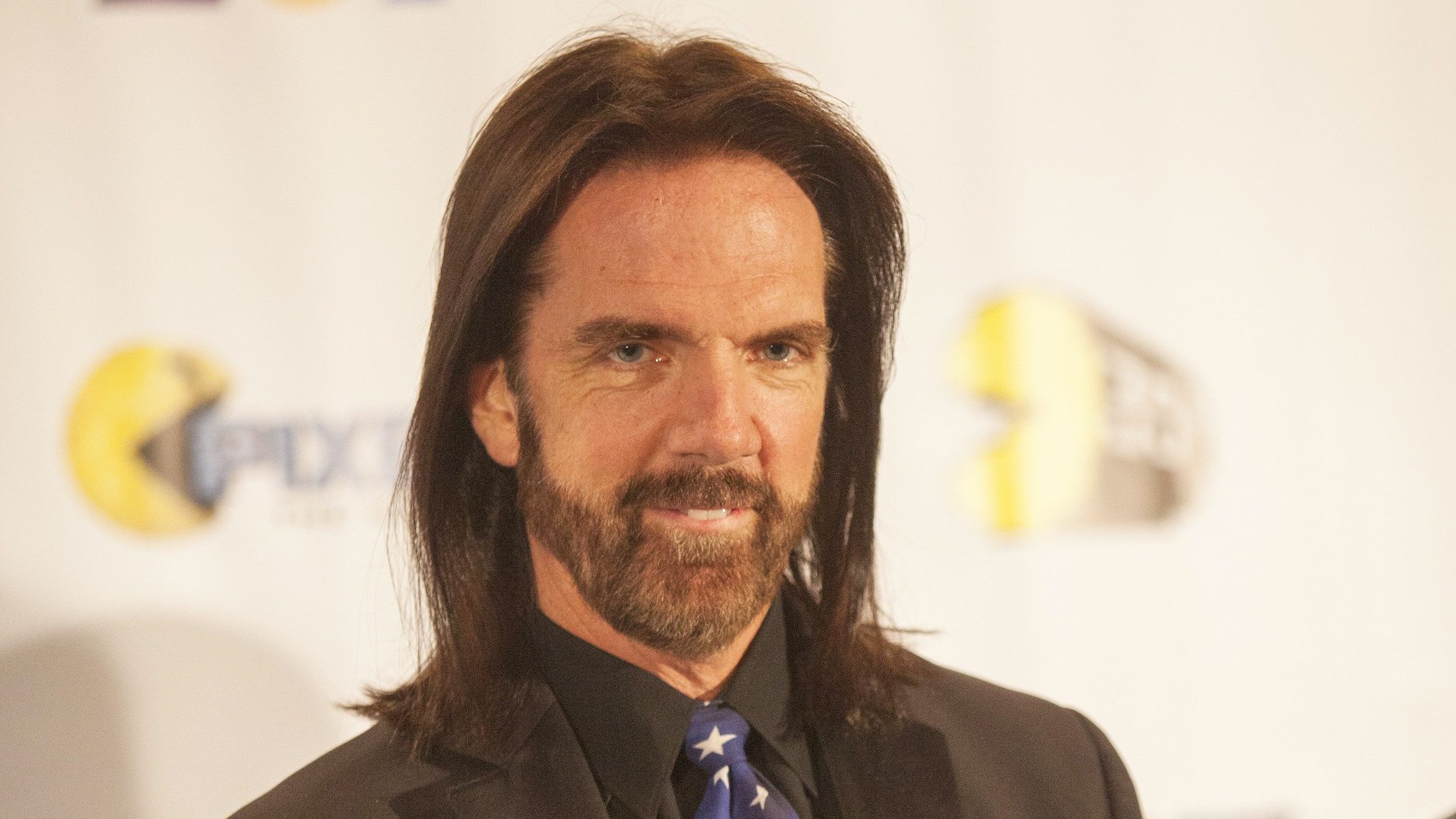

You might know him as one of the most famous players of video games in the world. In 2007, he featured prominently in the documentary “King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters,” about the world of competitive arcade players who chase high scores. Mitchell held the world record high score for “Donkey Kong” at the time; in the film, an unknown upstart named Steve Wiebe takes him on, turning Mitchell into the de facto villain. In the decade since, even as his scores fell off the top ranks, Mitchell’s charismatic personality and lanky presence — most always seen in his all-white suit and stars-and-stripes necktie– have dominated a certain corner of retro game culture.

But what he’s really good at is talking.

This past Saturday night, in the Marriott Renaissance Waverly hotel outside of Atlanta, during a panel at the Southern-Fried Gaming Expo, Billy Mitchell spoke into a microphone for over an hour, in front of a standing-room-only crowd, in his first stop on what he’s calling his “Road to Redemption.” He was there to explain himself in the wake of a recent controversy: that his world record scores, including the first ever million score on “,” were falsified.

Earlier this year, a forum moderator named Jeremy Young

posted evidence

claiming that Mitchell was not playing on original arcade hardware but on MAME, an emulator that could potentially be tampered with, making his play inadmissible. After considering Young’s dispute, Guinness World Records and Twin Galaxies stripped Mitchell of his scores. Mainstream outlets such as

this one

,

The Washington Post

and

NPR

reported the story. This was Billy Mitchell’s first public appearance since the firestorm.

—

Mitchell tells the crowd of nearly 150 people to be bold. “You’re here,” he says. “Don’t leave and say something silly. Ask me anything.” At this point, a man in front of me raises his hand. Mitchell continues to talk. The man slowly lowers his hand.

The panel includes

would-be interviewer Bobby Blackwolf

, podcaster and editor of VOG Network; he sits silent next to Billy for fifty-five minutes. And I don’t blame him. You don’t suggest chess moves to Garry Kasparov. You don’t give costuming advice to Edith Head. Billy is talking. So you let him talk.

“I don’t believe in journalism.” This is why he doesn’t do interviews — “I challenge any of you,” he says, looking over the crowd, “raise your hand and tell me the last interview I did. You can’t.” So when he does agree to answer questions, watch out.

“You’re in for a ride,” he tells Blackwolf, looking directly at him. He says this at 7:16pm. Blackwolf will not get a word in until 7:50pm, when, during a rare pause in Mitchell’s diatribe, he says, “So–” before Mitchell rolls on. Blackwolf will not say a full sentence until 7:56pm, after the fifth mention of sabotage and the first mention of pornography, when he continues his previous thought with a salient question: “So… why should we believe what you’re saying?”

More than setting high scores, Mitchell has become adept at telling stories about his record-setting performances. He doesn’t play these games very often anymore. Especially in public. When a reporter working on a profile for

Oxford American

in 2006 asked him to play “Ms. Pac-Man” at the Florida restaurant he owns and operates, a waitress raced over to watch: She had never seen him play in her nine years on the job.

This night would be another where he talked more, played less.

He says he came prepared to play “Donkey Kong” and show off his skills, but, alas, the organizers didn’t bring a “Donkey Kong” cabinet to the event. He shrugs his shoulders. That part of the redemption tour will come down the line. But for now, he names years and talks about videotapes and holds up a stack of printed out emails. Certain years and their respective high scores unidentifiable to your lay person reporter merits hoots and hollers from the crowd. A master storyteller knows his audience. He also knows his naysayers.

“They’re jealous crybabies,” Mitchell says, “who want to be worshipped sitting behind their keyboards.”

Certain parties have been targeting Mitchell and his accolades for years. “I’ve been called a threat,” Mitchell says, adding, “and I’m sure I’m that.” He knew, eventually, someone was going to paint a convincing enough picture, whether it was true or not. “This is guilty until proven innocent,” he says.

He holds up the stack of printed sheets again — “You can look at it all right here” — how the new owners of Twin Galaxies sought out someone to sabotage Mitchell and create fabricated MAME footage that could be linked to him, thereby setting up his great fall. But Billy Mitchell is not deterred. He has done too much to give up now. “I’m like a Formula One race car driver,” he says. “My job is to drive the car. Someone else does everything else.”

His suit is too white to become besmirched with the taint of wrongdoing. His necktie is too patriotic to be ripped asunder, only to float down like an eagle’s molted feathers. His hyperbolic talent is contagious.

He shares a saying his father told him once: “When you’re young,” he starts, looking out over a crowd of mostly forty-somethings, “you like going to the carnival and going on the rides. When you reach a certain age, you like to watch your kids go on the rides.” When he scored the first perfect game on “Pac-Man” in 1999 he thought he was done. He prefers watching all of us play, he says. In that moment we feel a kind of collective grace.

He then segues briskly into a story involving the FBI, his teenage son, pornographic material, and a mysterious ten-year-old girl. The same backroom cabal who, he says, orchestrated his downfall has been following the trail of his college-bound student-athlete son as he visits schools. Someone would email the coach after his son’s visit and suggest they don’t sign him, since his father associates with pedophiles.

“Come after me,” he says, choking up. “But don’t come after my family.”

The room is semi-stunned but waiting: For clarification, for what happens next, like a cabinet on Attract Mode awaiting its next quarter. Now is a good time to ask a question. At the mention of pornography and pedophilia, Blackwolf’s face scrunches up in the shape of the appropriate punctuation. Alas, as a shark must move in order to live, Mitchell just keeps talking.

A few moments after the p-word bombshell, Blackwolf finally, mercifully interrupts the Video Game Player of the Century with a very important message: We’re out of time. Mitchell looks at the organizers. “What’s more important than this that you’re kicking these people out?” We’re on a very tight schedule, they say. Only later will I look at the events page and see there was no other panel scheduled for that room after. Sometimes, with a live grenade on the ground, you run away. Sometimes you jump on it. Sometimes you let it explode.

Had Billy said this confusing metaphor, I would have nodded agreement. He had me and everyone under his spell. “Okay, one last thing,” he said. And then he sat and talked for ten more minutes. This was the end we should have expected. The panel was less an explosion than an hour-long seeping of odorless gas into a room full of waterlogged dynamite.

The man maintains his innocence and said he’ll prove he still has the necessary chops. Those who schemed to bring him down have only made him stronger. He’s booked at events across the country. He turned down an invite to Australia so he can watch his son play football. And at an upcoming event, he’ll retake his now-ruined records.

“I’ll do the same score [on ‘Donkey Kong’] and then I’ll let the game die.” But why wouldn’t you get a higher score, he asks himself, the only person he cares to give an answer to. “‘Cause I don’t have to,” he says. “I’m Billy Mitchell.”

In a response based on Pavlovian instinct and pure momentum, the crowd cheers.

As I leave the room, appropriately named “Chancellor,” I overhear the camera operator, who filmed the entire thing, giving his equipment to his wife for safe-keeping. “This is the most valuable camera in the world right now,” he says. The last thing I see is an audience member standing next to Mitchell and taking a selfie. Billy Mitchell is giving a thumbs-up sign, and as the fan lines up the shot, Billy raises his thumb higher, then higher still, making sure his thumb is visible in the frame.