Earl Gilbert, Now Retired, Championed Natural Lighting Techniques in Classic Films

By James C. Udel

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – Back in the age of directors calling “Lights, camera, action!” lighting was an unsung craft. One crew member who raised the bar, employing natural-looking illumination like an artist uses his brush, is gaffer Earl Gilbert.

Gilbert was born in Bakersfield, Calif., in 1926. His father, Ray, an electrician at Twentieth Century Fox Studios, helped Earl obtain union status via “the sons of members” provision. Joining in late 1946, Earl aced a grueling four-hour test pulling pound-a-foot cable 60 feet above the stage.

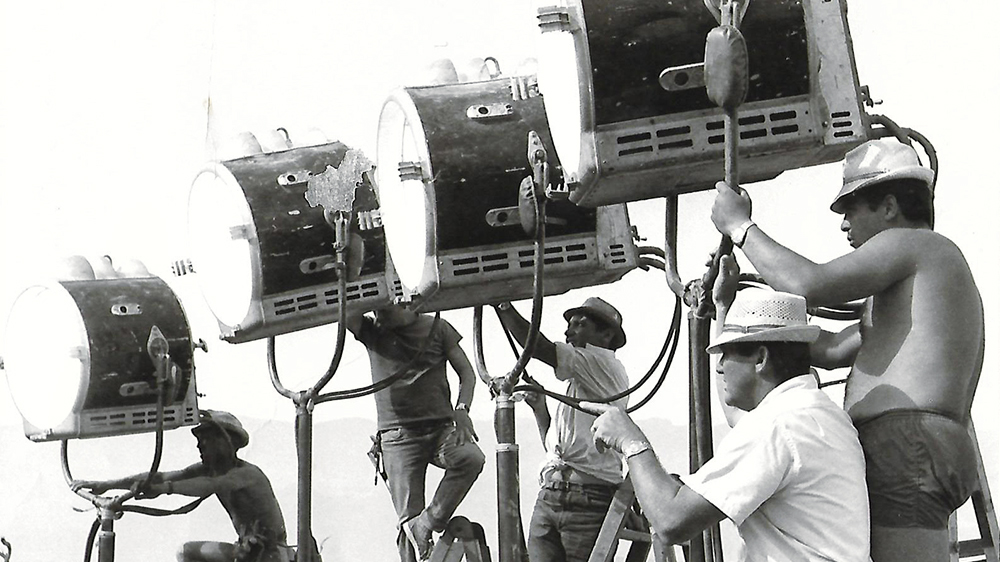

Serving as a rigger on pictures “Forever Amber” and “Gentlemen’s Agreement” (both in 1947) and “The Day the Earth Stood Still” (1951), Gilbert first demonstrated a talent for lighting on Elia Kazan’s 1952 “Viva Zapata!” He waterproofed a 12-light fixture for submersion, with the lamps covering a scene in which a horse gallops into a river as the camera drops below water level and the rider is shot and falls off. Gilbert’s contribution was memorable to all who saw the scene, as the bandit’s macabre death grimace was clearly discernible when he sank. The lighting tech achieved the effect while working his rig wearing only shorts, a mask and a homemade weight belt.

Continuing with Fox into the 1950s, Gilbert helped light classics such as “The Robe,” two Marilyn Monroe starrers — “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” and “Bus Stop” — and “Boy on a Dolphin” (with Sophia Loren). On “Blondes,” he recalls Monroe being shy but Jane Russell being gregarious: Russell’s cry of “Howdy, Earl!” each time she greeted him on set, he says, made him feel like a million bucks.

From serving as follow-spot operator for Yul Brynner’s waltzes in “The King and I” to setting up futuristic Tesla coils for Vincent Price starrer “The Fly,” Gilbert was a go-to guy around the lot in the ’50s. He had earlier become best boy for Homer Plannette, the gaffer on “It’s a Wonderful Life” (1946), and it was a fitting marriage, leading to a student-teacher relationship and collaboration on such films as “Mr. Hobbs Takes a Vacation” (1962).

Gilbert developed the art of using available location lighting. He “borrowed” electricity by scaling telephone poles and tapping into overhead power lines — a gambit that risked electrocution.

By the 1960s, he was in great demand. He gaffed “The Graduate” (1967) using high contrast ratios; “True Grit” (1969), lit by single source to mimic a kerosene lamp; and “Catch 22” (1970), with its ethereal clouds of B-25 bombers illuminated in every way imaginable. His work had a limitless texture every DP wanted.

Yet it was movies like Sam Peckinpah’s “The Getaway” and Richard Fleischer’s “The New Centurions” (both 1972) that best reflected Gilbert’s natural look. And he also brought light to DP John Alonzo’s lens on “Chinatown,” using a single high beam on Jack Nicholson’s face in the scene where the actor’s J.J. Gittes has his nostril sliced open, and subtly lighting Faye Dunaway’s close-ups with ambers and straw gels to beautify her facial tones.

Now retired and interviewed by Variety in his comfortable home in Thousand Oaks, Calif., Gilbert reminisces about the looks he helped create for such films as Kazan’s “The Last Tycoon” (1976) and Steven Spielberg’s “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” (1977). His final credit was on “The Butcher’s Wife” in 1991. As he talks, he makes a startling revelation: “I never used a light meter,” he allows. “If it looks good, it is good, and if it’s not, fix it!”

“Action!” indeed.