‘Making a Murderer’ Creators Make the Case for Season 2

By Debra Birnbaum

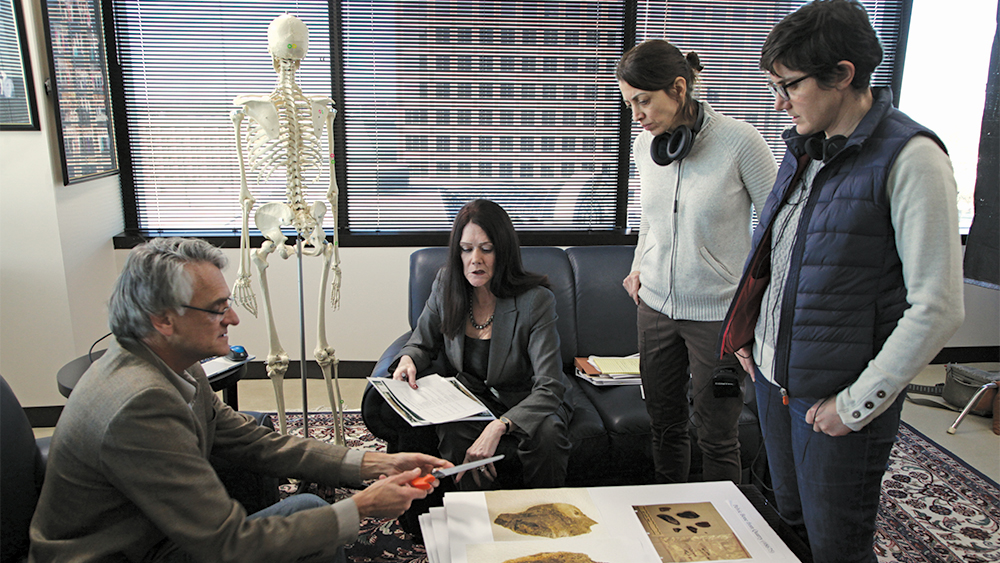

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – Few were as surprised at the eruption that followed the release of the first season of Netflix’s documentary “Making a Murderer” as the filmmakers, Moira Demos and Laura Ricciardi. They had set out to recount a tale of social justice — or injustice, depending on your point of view — as they traced the case of accused killer Steven Avery, who’d been exonerated on a separate, unrelated charge after spending 18 years behind bars. “It’s a window into the American criminal justice system that we haven’t seen before,” Ricciardi tells Variety. “We wanted to know how that happened and what would be happening to him as an accused in the system.”

The first season, which detailed the 2005 trial and convictions of Avery and his nephew Brendan Dassey for the murder of Teresa Halbach, ignited a firestorm. Advocates on either side argued vociferously over the men’s guilt or innocence — and also demanded a second season, which was greenlit in July 2016, seven months after the premiere, and bows on Oct. 19.

“We knew that this story wasn’t over,” Demos says. Adds Ricciardi, “In part two, we wanted to look at the experience of the convicted and imprisoned, two people who are serving life in prison, maintaining their innocence, and wanting to fight to regain their freedom. For us, the central dramatic question for part two was, will these two individuals succeed?”

But Season 2 presented its own set of challenges: Not only had Demos and Ricciardi, once anonymous, become stars themselves (“We did not want to become subjects in the story,” says Ricciardi), but there’s now a worldwide laser focus on every motion filed. A basic internet search will reveal that both men are still behind bars, with their latest appeals denied by the courts.

“I would argue it’s not the whole story you can find on Google,” says Demos, who promises “major discoveries” to come. “You may know the outline, but you don’t know the story.”

And then there’s the matter of the barrage of criticism flung at them, which they tackle head on: The first episode starts with an extended, five-minute-long cold open detailing all those alleged flaws before diving into the myriad twists and turns that have unfolded since.

“I think one of the main criticisms we heard was that we minimized evidence that would have tended to prove ’s guilt,” says Ricciardi. “From a storyteller’s perspective, it’s a ridiculous allegation because the greater the conflict, the greater the drama. We wouldn’t choose to minimize something that would have been stronger evidence for the prosecution.”

Particular attention is given to the “sweat DNA” that was found under the hood of Halbach’s car and identified as belonging to Avery. That would become one of nine key pieces of evidence being investigated by his new defense attorney, Kathleen Zellner, who takes on the case with a stern warning to her client that she’ll drop it if she finds evidence of his guilt. As her investigation leads her from the crime scene to the DNA lab, she serves as a proxy for the viewer trained on years of watching crime shows.

Despite the criticism, the filmmakers say they wouldn’t have done anything differently. “In Season 1, I think we were a little naive in terms of not realizing that people wouldn’t understand our process, so we didn’t necessarily put our process up front,” says Demos. That’s why Season 2 includes a card at the end listing everyone who declined to participate.

They argue, too, that they don’t believe the notoriety they brought to the case has impacted it. The district attorneys “do believe in the convictions that they obtained,” says Ricciardi. “They do think that Steven Avery and Brendan Dassey are where they belong.”

The filmmakers insist, though, that they don’t have an opinion on the men’s guilt or innocence. “What we were doing was holding a mirror up to the process,” says Ricciardi. “We did come away with our own opinion of whether we thought the process was fair, and whether or not the state met its burden. We don’t believe that the state did. But do we have an opinion about who might have killed Teresa Halbach? Absolutely not. We have no idea.”

Instead, the message they’re trying to convey is that we all need to pay more attention to the vagaries of the criminal justice system. “Having documented this story for 13 years and created 20 episodes of television about it, I can comfortably say that I would want to be treated much better than what I witnessed here,” says Ricciardi.

Adds Demos, “And you should under-stand that the problems of the world are not irrelevant to you, and they could come down on you.”