Hollywood’s Great Depression: Meet the Entertainment Workers Left Jobless by the Coronavirus Pandemic

By Brent Lang

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – Mac Brandt was one of the lucky ones.

For the past six years, he’s made a living purely from acting, appearing in television shows like “Kingdom” and “Arrested Development,” and scrounging up enough jobs to pay the bills without having to tend bar or wait tables. But life changed drastically for Brandt and much of the entertainment industry in March, when work ground to a halt as the coronavirus swept across the country. Movie theaters have gone dark, soundstages have shut their doors and productions have been delayed indefinitely, leaving tens of thousands of people like Brandt jobless and forced to navigate a grim economic landscape.

“I was on ‘Station 19’ the other night and people must be going, ‘Oh this guy’s on TV; he must make a lot of money,” says Brandt. “But it’s a working-class industry. You have to string together enough work and keep auditioning in order to keep going. I can’t do that with everything shut down.”

In the meantime, Brandt has filed for unemployment and obtained deferrals on his mortgage and car lease payments. He’s going to refrain from paying off his credit cards, so he’ll have enough money to buy essentials. And he’s waiting for a $1,200 stimulus check from the federal government.

“If I paid all my bills, I wouldn’t have money for groceries,” says the 39-year-old actor. “So you prioritize. I’ve got two young kids, and the other night I was freaking out and thinking maybe I should get a job at Amazon.”

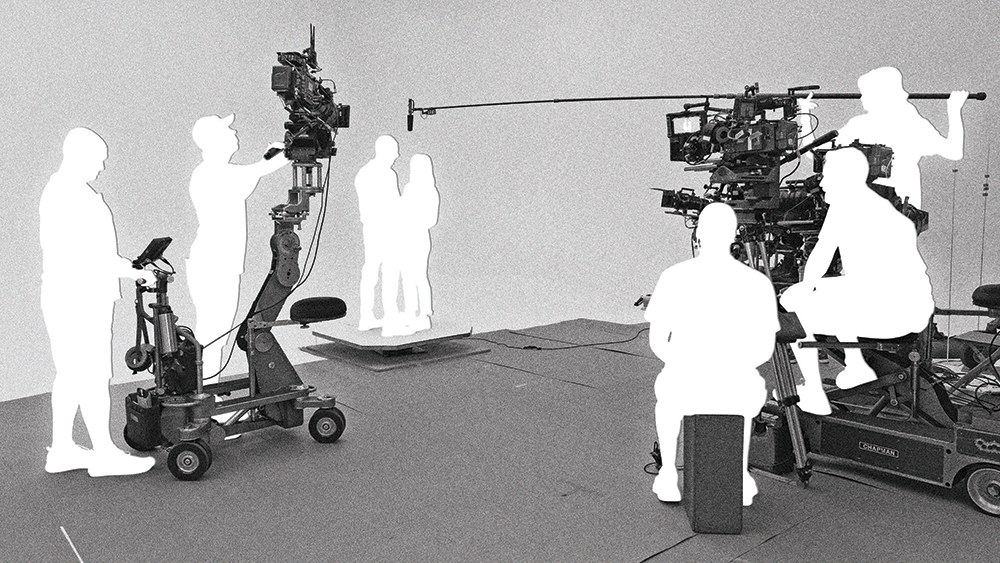

The shutdown has lasted for less than two months, but in that short time the fallout from the pandemic has brought the film, television, music and theater businesses to their knees. It’s the greatest economic calamity to ever hit Hollywood, Broadway and other entertainment business hubs, dwarfing the wreckage left by such recent catastrophes as 9/11 and the Great Recession. And it’s being felt most acutely by production designers, camera operators, makeup artists, grips, stagehands, ticket takers, casting directors and character actors, whose names may not adorn cinema marquees but whose work forms the backbone of the business.

In February, the Motion Picture Assn. estimated that the film and TV industry directly employs 892,000 people. It’s not yet known how many of those jobs have been lost, but it’s possible to make a rough guess. According to federal data, about 125,000 of those employees are movie theater ushers and concessionaires — nearly all of whom have been furloughed or laid off. Another 170,000 work as actors, directors, camera operators, lighting technicians, set designers and other production workers — a large percentage of whom are also not working.

“If I paid all my bills, I wouldn’t have money for groceries. The other night i was freaking out and thinking maybe i should get a job at Amazon.”

Mac Brandt, actor

Related industries have entirely shut down. Nationwide, about 72,000 people work for theater companies. Some 210,000 people work for amusement parks in the U.S., of which about 150,000 are employed in frontline capacities like food service, ride operations, security and janitorial service. The vast majority of them are now on furlough. In sum, several hundred thousand people in the entertainment business, broadly defined, have likely lost their jobs since the first week of March — many times more than lost their jobs in the Great Recession.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen,” says Anka Malatynska, a 40-year-old cinematographer whose credits include HBO’s “Insecure.” “I don’t know what’s going to happen in America when people have to pay rent and they’re not making any money.”

A-listers like Brad Pitt and Jennifer Lawrence may make headlines for their lavish paychecks and endorsement deals, but they’re the exception to the rule. People who enter the entertainment business have a high tolerance for risk and are no stranger to side gigs as they hustle to make money while waiting for a big break that may never come. But when work dried up during the coronavirus, it left them with few ways to earn a living. After all, it’s hard to wait tables when most restaurants are closed.

“It’s not like I can apply for one of the nonexistent jobs out there,” says Mo Stemen, a 35-year-old production coordinator on “Fast 9” and “The Morning Show.” “The only company hiring right now is Domino’s.”

The economic carnage from the closures has exposed how close to the edge many workers in the entertainment industry were living before things shut down. Paula Owens was employed by Wilson Amusements when she was 15 years old, in one of its restaurants. Thirty-eight years later, she manages the company’s movie theater in Atlantic Beach, a tourist town on the coast of North Carolina. For her entire life, she never had to worry about her next paycheck — until last month. The theater closed down on March 16 as the pandemic spread across America.

A single mom, Owens is now at home with her 19-year-old daughter. She’s collecting unemployment — but so far the checks have been about half of what she’s used to.

“It’s the first time I’ve ever had to ask for anything from anybody,” says Owens. “I’m blessed compared to others. Things are paid through April, but May is quickly approaching.”

Most people who work in physical production aren’t full-time employees. They’re freelance workers, who move from job to job, which sometimes requires them to decamp for different states as movies or shows go off in search of the best tax breaks. Their reliance on a gig economy has caused myriad problems when applying for unemployment benefits. Many have spent the past few weeks desperately trying to reassemble a patchwork of past employers to get some relief.

“I worked in four different states, and when I talked to my accountant, she said to apply for unemployment in every state,” says Malatynska. “Monday to Friday, it feels like I’m on this pseudo-apocalyptic vacation, and I’m buried in my computer trying to make backup financial plans.”

Across the country, unemployment agencies have been inundated with applications. That’s led to website crashes and other frustrations. It’s nearly impossible, workers say, to find someone to answer questions — a persistent problem given the difficulty that many entertainment industry employees face in tracking down previous employers or dealing with the hurdles of being listed as independent contractors.

“They are so behind,” says Mike Testin, a 45-year-old cinematographer. “You could sit on the phone all day and never get in touch with anybody, and they’re only open from like 8 a.m. to noon. So the window of time is very small, and they’ve been just crushed with so many claims that it’s hard to actually get somebody — get a human — to answer a question.”

Some companies, such as Netflix, WarnerMedia and Viacom, and unions have started funds to support people who have lost work during the shutdown. That’s helped workers string together a lifeline, even though many are worried that cash will run out if the closures stretch on through the summer or if work resumes, only to be halted again by another outbreak.

“We’re totally in a standstill and living off of savings or actors funds or whatever other union help we can get,” says Iris Abril, a 47-year-old makeup artist on “Brooklyn Nine-Nine.”

The pandemic has caused an employment crisis like no other. In five weeks, 26 million Americans filed unemployment claims. Those include hotel and restaurant workers — who were among the first to feel the brunt of the shutdown. But the devastating effect has spread across the economy, from the luxury stores on Rodeo Drive to the taconite mines of northern Minnesota to the lobster piers of coastal Maine.

The April unemployment rate, which will be released on May 8, is expected to surge, though by how much is unclear. Many sidelined workers are not looking for jobs, and therefore won’t be reflected in the official tally. But some economists expect the “true” unemployment number to come close to 20% — or nearly double the worst figure from the Great Recession. In 2008 and 2009, the motion picture industry shed 31,000 jobs. By now, that figure could easily be eclipsed many times over.

“We’ve blown past in two months what it took two years to get to in the Great Recession,” says Bill Rodgers, a labor economist at Rutgers University and a fellow at The Century Foundation. “We’re really at the mercy of the virus.”

Though hard numbers are hard to come by, the major guilds, such as the unions that represent costume designers, camera operators and makeup artists, predict that as many as 98% of their members have been furloughed.

“I can say that because production has shut down everywhere, [our members] are not working,” says Terry McCarthy, CEO of the American Society of Cinematographers. “It is as simple and stark as that.”

Then there are the thousands of theme park workers who started March with a steady income and ended it on the dole. Disney shuttered its parks around the world last month, and put some 100,000 workers on furlough starting April 19.

Marquis Howell, who plays guitar and bass in the Five & Dime show at Disney California Adventure in Anaheim, says the company gave him $193 a week for the first two weeks of the shutdown. He is struggling to pay his rent and has been unable to get unemployment. “I’ve tried to register — it just goes into the void,” he says. “I’m getting ghosted.”

Howell, who is 39, has a 12-year-old and 4-year-old triplets. He says Disney usually makes up about a third of his income, with the rest coming from playing in bands.

“It’s all gone; it’s all shut down,” he says. He has been able to make about $1,200 from “tip videos” — online performances where viewers can send him tips via Venmo. “That money has started waning,” he says. “My friends have all given.”

There’s also a slew of ancillary business, from florists to hairdressers to caterers, which orbits the entertainment industry and depends on everything from providing lunch for hungry casts and crews to offering up style tips for red-carpet events to make a living. Those jobs are in jeopardy. Tara Swennen, a 40-year-old stylist whose clients include Kristen Stewart and Allison Janney, usually juggles about three to four jobs a week. Those gigs have dried up in the wake of COVID-19, and it’s unclear if they’re coming back.

“Every press tour is being done virtually via Zoom, so we have just been cut out of the process,” she says. “We don’t know what will happen in the future. Will studios decide they could do press virtually instead of something like big junkets at the hotels or making the rounds at morning shows and talk shows? If it’s all virtual, the stylists could be cut out completely.”

The theater industry — which was struggling to begin with — has been hammered. On a single day in March, Cinemark declared that it had laid off 2,555 people in California alone, and the National Assn. of Theatre Owners predicts that as many as 150,000 exhibition workers have lost their livelihood.

“It was pretty devastating to have to look people in the eye that you’ve worked with for your whole life and say, ‘We have to furlough you,’” says Brock Bagby, executive VP of B&B Theatres, a Missouri-based cinema chain. “There were lots of tears happening on both sides.”

The entertainment industry typically thinks of itself as relatively “recession proof,” because people seek escape during hard times. But this go-round, no one is immune. In New Orleans, 56-year-old Rene Broussard operates the Zeitgeist Theatre & Lounge, a single-screen rep house.

“I was working every day except Tuesday and Wednesday,” he says. “Now I’m stuck at home with my 85-year-old mother with Alzheimer’s and my sister who’s a cardiac patient, who I’ve become the sole caregiver for.”

Broussard is able to stream movies on his theater’s website. Visitors pay $12 for art-house films, of which $6 comes back to him.

“It’s helping, but this is next to nothing compared to what we were doing,” he says. “We’re not getting any concessions revenue. That’s what we survive on.”

He has run the theater, in one location or another, for 33 years. Last year, he was recruited by a charitable foundation to move to an arts district in nearby Arabi. The rent is relatively cheap, he says, and the foundation has been understanding about the emergency.

“They were great about the April rent,” he says. “We haven’t talked about May yet.”

Broussard has been filling his time by applying for aid. He expects to get $300 from the Will Rogers Pioneers Assistance Fund, which helps theater workers in need. He has been unable to get unemployment benefits, but has been told to keep applying.

After Hurricane Katrina, he says business flourished as young people flooded into the city to help rebuild. This time, though, he’s not so sure the audience will be back.

“When theaters reopen, a lot of people will have gotten used to watching things on their TVs,” he says. “I’m determined to reopen if I can — when I can — but they’re not giving me much hope.”

For actors, a lack of auditions isn’t stopping some from getting creative. Kaitlin Puccio, a 30-year-old actor and model in New York, was trying out for upcoming television shows when the coronavirus halted pilot season in its tracks. Now she’s focusing on getting voiceover work, about the only kind of acting gig that can be done remotely. To get ready, Puccio transformed a closet in her apartment into a makeshift recording studio, outfitting it with soundproofing and a microphone.

“It beats trying to record voiceovers under a blanket,” says Puccio. “It’s not just about making money for me. It’s about wanting to keep practicing and wanting to stay in the mindset of trying to get work. You can’t allow yourself to stop pushing forward.”

In many cases, the coronavirus slammed the brakes on busy careers. Alistair David, a 44-year-old choreographer, was enmeshed in rehearsals for a U.K. production of “Sister Act” with Whoopi Goldberg and Jennifer Saunders. In August, he was scheduled to design the dances for a musical version of “My Best Friend’s Wedding,” slated to debut in London’s West End. All of those plans are now on pause.

“It’s not knowing the end of this that’s unbearable,” says David. “There’s no timeline for when things go back to normal. I’m just stuck staring into the abyss of the unknown.”

When the virus first upended life, there was a popular meme on social media reminding people that Shakespeare wrote “King Lear” while quarantined during the plague. David’s friends and family have urged him to be similarly productive during his own period of social isolation.

“People will say, ‘Why don’t you use this time to write a book?’” says David. “Well, I’m not a writer. My trade is my trade, and I’ve never wanted to be anything other than a good choreographer. So until I can do that, I’m stuck working on puzzles and just trying to get through it.”

Even if life slowly returns to normal, David is skeptical that people will want to spend time in crowded theaters with strangers who may be carrying the coronavirus. “It feels like our industry is going to be really affected, because we literally group people together in a small space,” says David. “Are we going to fill up half the theater? Are we going to make everyone wear masks?”

As with David, Chad Kimball’s career was buzzing when the pandemic gripped society. He had a prominent role in “Come From Away,” the long-running Broadway musical about a community rallying in the aftermath of 9/11. But Kimball, 43, didn’t just have to grapple with canceled performances and a lack of paychecks. He was one of the thousands of Americans who came down with the virus. In March, a dry cough developed into a low-grade fever, a headache and intense body aches. The symptoms dogged him for two weeks, but Kimball was fortunate. He never had to be hospitalized. As he recovered, he took to social media, answering fans’ questions and drawing attention to the disease.

“My immediate response to things, as an actor and as a person, is to shout about them to the world,” says Kimball. “For better or worse, I realized I would be able to put a face to the virus, especially for people in parts of the country who might not be seeing a lot of cases. I want people to know that this disease touches everyone. It does not discriminate.”

Kimball isn’t done giving back. He wants to donate his plasma, so that doctors can use the antibodies in his blood to help others recover from the coronavirus.

“There’s no timeline for when things go back to normal. I’m just stuck staring into the abyss of the unknown.”

Alistair David, Choreographer

“My blood is actionable right now,” says the actor. “People need these antibodies. It’s wonderful that this horrible thing that happened to my body can do incredible things for someone else.”

It’s unclear when cameras will start rolling again and theaters will open their doors. Many who have lost jobs fear they will return to a business that’s unrecognizable. They expect that audiences will have to social distance, performers may have to wear masks, and cast and crew members will have to subject themselves to temperature checks and routine testing for the virus. Production coordinators like Mo Stemen say that will require logistical challenges, and will likely add days to shoots and cause budgets to balloon.

“People get frustrated if their name isn’t at the studio gate and they have to wait five minutes,” says Stemen. “It’s going to take an hour or more to get tested every morning and fill out a questionnaire with all your medical information. And I’d assume there are all kinds of privacy issues with that. Then we have to sanitize the sets and make sure you’re getting companies that are certified to do that work. It’s going to have all kinds of ripple effects.”

Studios and unions are trying to work out how they can go back to work with skeleton crews, arguing that reducing the number of people on a set reduces the risk of exposure to COVID-19. That means, however, that even when movies and television shows resume shooting, there will be fewer jobs to go around. There are even fears that people will be so desperate to go back to work that they’ll be willing to settle for less.

“I’m worried people will take pay cuts,” says Stemen. “There’s going to be more competition for jobs, and if people are willing to take lower rates, that puts all of us in a really bad position.”

It’s also likely to have an artistic impact. Studios, already risk-averse before the coronavirus erupted and bruised from enduring months without revenues, may focus almost solely on making franchise films and comic book adventures. Those bottom-line decisions will be at the expense of the kinds of edgy and daring stories that made most people want to get into filmmaking in the first place.

“It’s going to leave a big void,” predicts Biz Urban, a 41-year-old casting associate whose credits include “Bunk’d” and “The X-Files.” “When studios are greenlighting things, are they really going to want to take a chance on something that’s not tried and true?”

By the time public health officials declare it safe to return to set, some people likely will have been forced to leave the business entirely. Many laid-off and furloughed workers say that they are only able to wait out the closure for a few more weeks before having to look for other ways to earn a living.

“I am mentally preparing myself for the possibility that this could become a long-term thing,” says Steffen Schlachtenhaufen, a 41-year-old writer and documentary filmmaker. “The industry may contract, and a lot of our careers may get delayed or may end. It’s possible that I’ll have to move on to something else.”

Adam B. Vary, Marc Malkin, Rebecca Rubin and Jazz Tangcay contributed to this report.