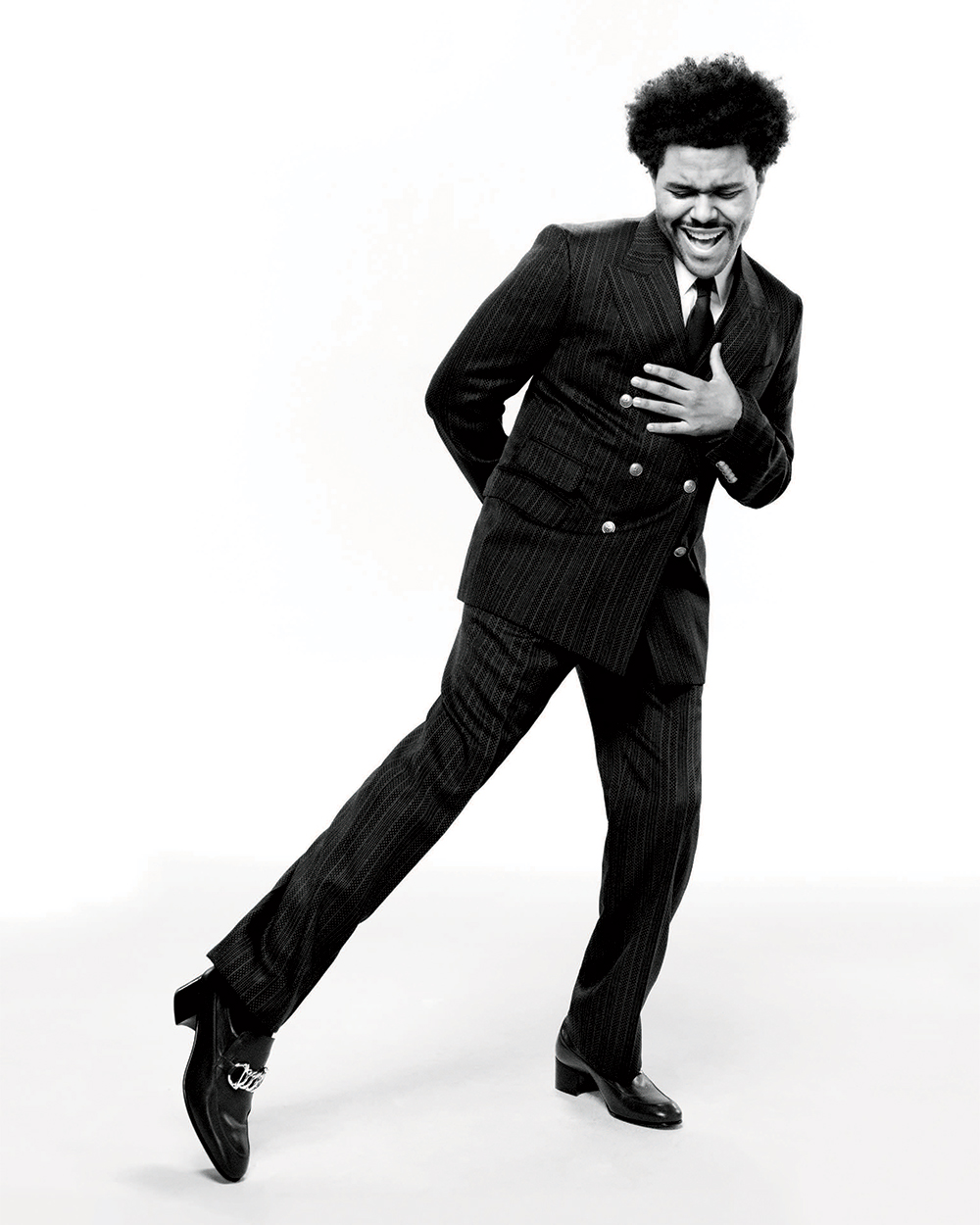

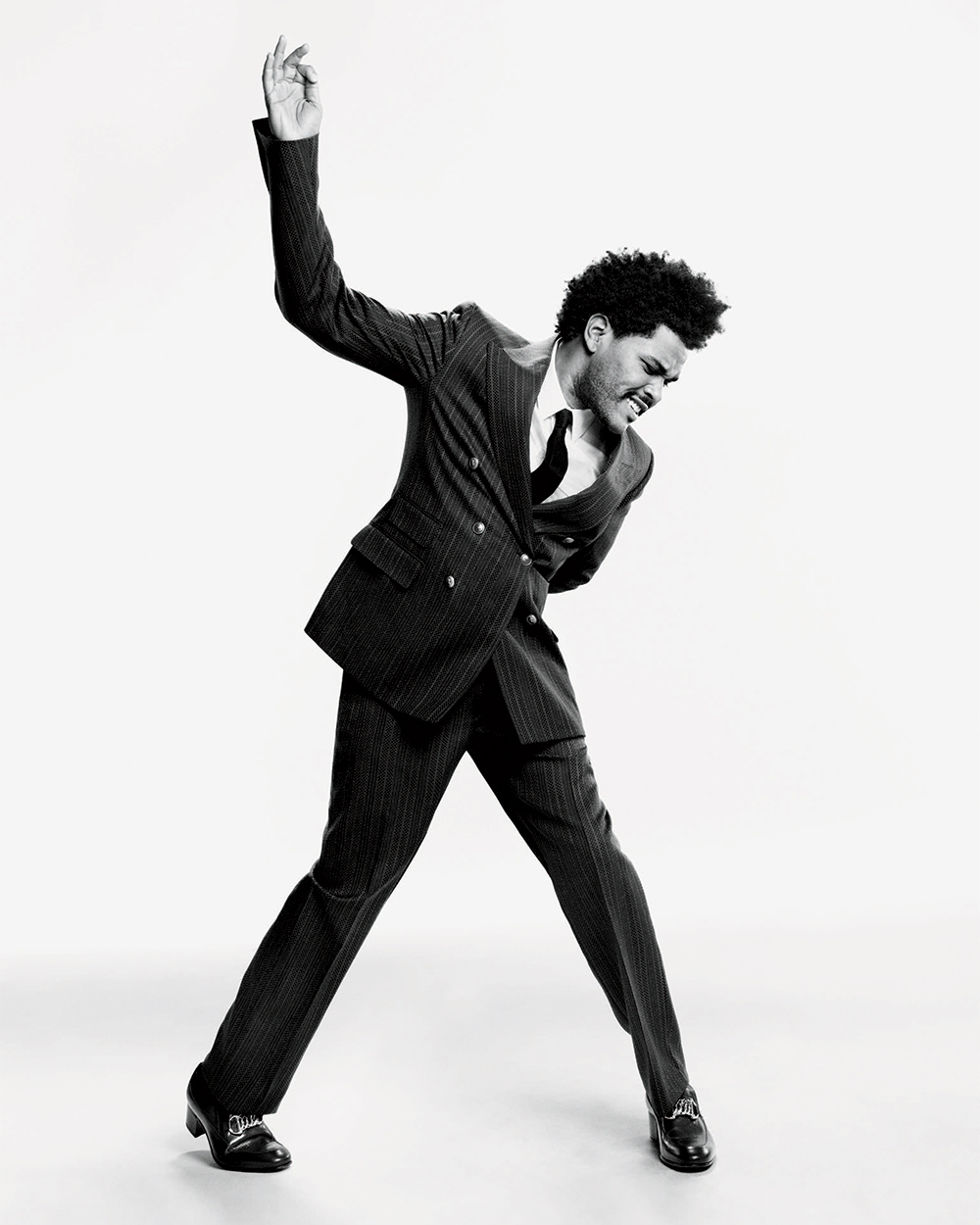

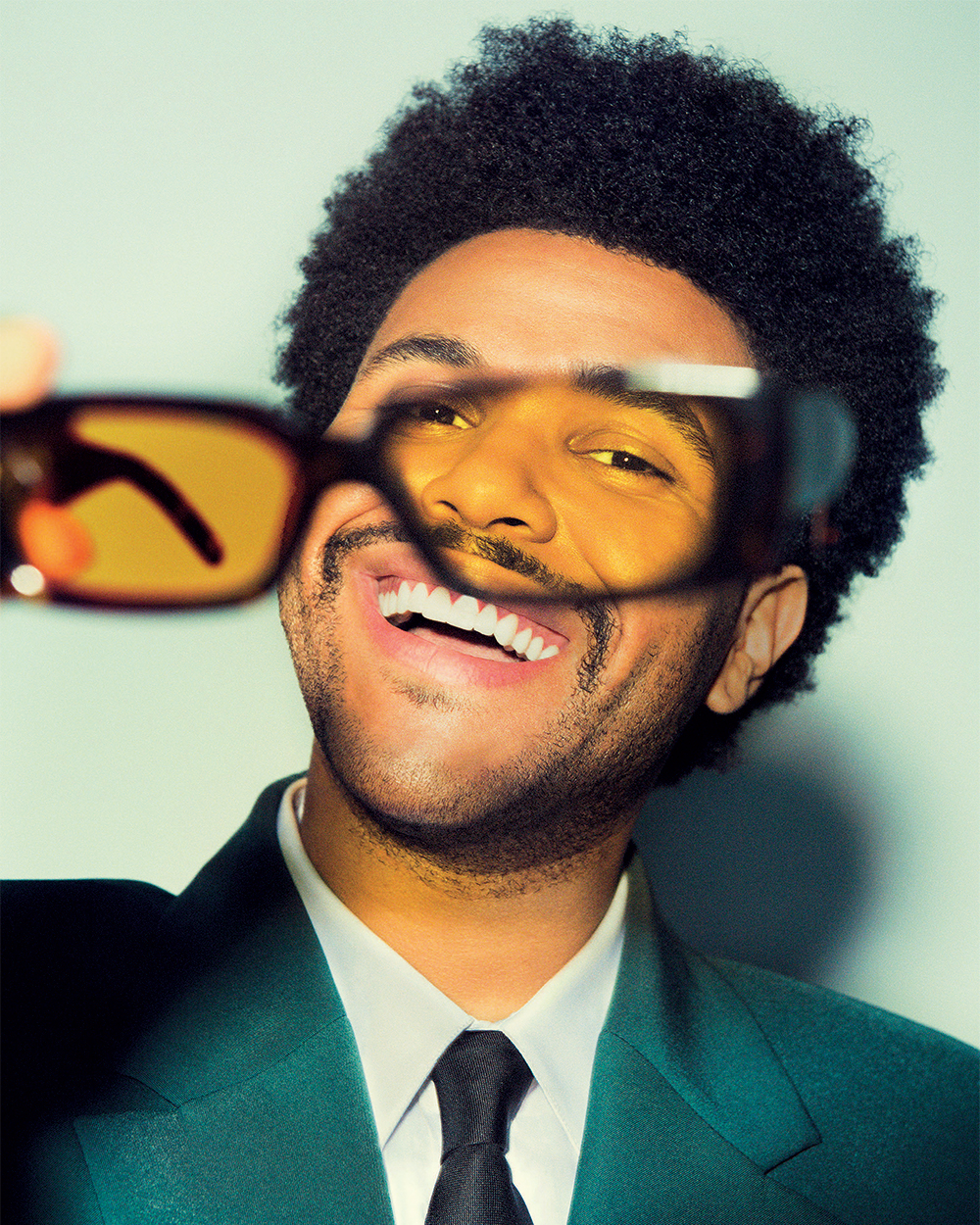

The Weeknd Opens Up About His Past, Turning 30 and Getting Vulnerable on ‘After Hours’

By Jem Aswad

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – On the afternoon of March 5, the artist known as The Weeknd is at a rehearsal for his appearance on what will be the last live episode of “Saturday Night Live” for the foreseeable future — although no one realizes it at the time. The iconic Studio 8H at 30 Rock bustles with activity as he prepares to run through his two performances and tape promos for the show with cast member Cecily Strong and host Daniel Craig, whose next James Bond film, “No Time to Die,” has just been postponed from an April release date to November due to the rapidly spreading coronavirus pandemic.

Apart from a couple of stagehands wearing gloves or surgical masks, there’s little indication of the panic that’s just days away. Dozens of people move around the small space, and there are hugs, handshakes and close contact all around, including when Weeknd (real name: Abel Tesfaye) and Craig meet for the first time and exchange several minutes of friendly chat. “I just totally geeked out on Daniel Craig,” he is heard confessing to a team member afterward.

The Weeknd, Craig and Strong gather in front of the show’s iconic stage to tape the promos, one of which makes a light joke about coronavirus isolation in the show’s trademark off-hand yet envelope-pushing manner.

“Due to coronavirus, we’ll be broadcasting remotely,” Strong says, then gestures at The Weeknd and adds, “Actually, we’ll be remote, but you’ll be here in the studio.” Weeknd looks at the camera with a nervous smile intended to display comic timing but instead reflects a nagging collective twinge that maybe this isn’t such a good thing to kid around about.

The promo never airs.

It’s one of many pivots not just in the rollout of “After Hours,” The Weeknd’s first full-length album in three and a half years, but in an entertainment industry and world that is flailing to come to grips with a new reality. While the album ultimately was released to r apturous response from critics and fans as planned on March 20 — at the end of a horrifying week when the grim reality of the pandemic’s magnitude finally struck the United States — that date was by no means a foregone conclusion. Albums by Lady Gaga, Alicia Keys, Sam Smith, Willie Nelson and many others have been pushed several months, due to practical matters of marketing and touring as well as the bigger concern of appearing tone-deaf or insensitive to the fast unfolding tragedy.

The Weeknd’s team — including longtime managers Wassim “Sal” Slaiby and Amir “Cash” Esmailian and top executives at Republic Records — considered the possibility of delaying the album, which was to have been supported by a world tour scheduled to launch June 11 in Vancouver and stretch across North America and Europe through November, with another leg to follow in 2021.

But “I cut that discussion off right away,” The Weeknd says. “Fans had been waiting for the album, and I felt like I had to deliver it. The commercial success is a blessing, especially because the odds were against me: [Music] streaming is down 10%, stores are closed, people can’t go to concerts, but I didn’t care. I knew how important it was to my fans.”

Indeed, the numbers — even by the standards of an artist who’s racked up a whopping 44 gold- or platinum-certified singles and albums since his 2011 debut — bear out how accurately he read the room: 2 billion global streams, nearly 2 million in global consumption (a combination of streams and sales) in its first week, easily debuting at No. 1 in the U.S., his home country of Canada, Australia, the U.K., Ireland, Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy and New Zealand.

Creatively, the album is just as much of a success. Powered by the smash lead-up singles “Blinding Lights” and “Heartless,” it’s a combination of bangers and ballads that musically finds him seeing just how much he can challenge his fans while remaining a commercial powerhouse — and emotionally reflects the maturing perspective of someone who just turned 30, as The Weeknd did in February. ( Head here for a long interview with The Weeknd about the album, its concept, videos, creation and more .)

To that end, he’s made “After Hours” as much a visual narrative as a musical one. On the album’s cover, in its videos and in his late-night TV appearances (including “SNL”), The Weeknd portrays a red-jacketed, busted-nose character undergoing an extremely dark night of the soul in Las Vegas. He starts off partying and gambling, then gets beaten up in a fight, and as the loose, still-evolving plot unfolds across multiple clips, things get really weird, as he (possibly) becomes possessed by an evil spirit and commits a murder. Like much art of this nature, it also hints at a look into the heart of its creator, leading to fan and media speculation about high-profile exes — in The Weeknd’s case, Bella Hadid and Selena Gomez — and of past debauchery and bad behavior toward oneself and others.

The persona shows off his budding acting chops even more than his recent big-screen debut in the Safdie brothers’ “Uncut Gems” (where he portrays himself), and the videos are loaded with Tarantino-size film-geek references to classics like “Chinatown,” “Dressed to Kill,” “Possession” and, not least, “The Mask,” the 1994 film starring fellow Scarborough, Ontario, native Jim Carrey, which played a pivotal role in The Weeknd’s life.

“‘The Mask’ was the first film I ever went to see in a theater — my mom took me when I was 4, and it blew me away,” he enthuses. The two mutual fans were introduced in a text last year, and Weeknd invited Carrey to hear some of his new music. “I texted him the address of my condo in L.A., and he said, ‘I can literally see your place from my balcony,’ and we got out telescopes and were waving to each other,” he continues. “And when I told him about my mom taking me to see ‘The Mask,’ he knew the theater! Anyway, on my [30th] birthday, he called and told me to look out my window, and on his balcony he had these giant red balloons, and he picked me up and we went to breakfast.” He smiles. “It was surreal. Jim Carrey was my first inspiration to be any kind of performer, and I went to breakfast with him on my first day of being 30.”

This particular moment is also a little surreal because Weeknd is telling the story at the “SNL” rehearsal, with his busted-nose makeup on, complete with fake bruises and dried blood. It’s a slightly disconcerting way to have a conversation.

He laughs and touches his fake-bandaged nose. “I forget that I have it on sometimes.”

As part of The Weeknd’s first sit-down interview in nearly five years, he offers Variety a private advance preview of “After Hours” in its entirety at Alicia Keys’ Jungle City Studios in New York. Such intimate experiences have enormous potential to be awkward for both parties — what if the music is terrible? — but that’s not an issue here: “After Hours” is indisputably The Weeknd’s most mature and fully realized album to date, with songs that question the narrator’s hard-partying, womanizing, substance-abusing ways against a sonic backdrop of cinematic keyboards, pulsating sub-bass, hard beats and ’80s synthesizer flourishes. Longtime collaborator Max Martin — the most successful songwriter-producer of the past 25 years, with hits for artists ranging from the Backstreet Boys to Taylor Swift — is present on several songs, as are The Weeknd’s core sonic team of DaHeala and Illangelo (né Jason Quenneville and Carlo Montagnese), along with new collaborators like avant-garde electronic musician Oneohtrix Point Never (Daniel Lopatin), Tame Impala mastermind Kevin Parker and Lizzo’s behind-the-scenes wizard, Ricky Reed.

It also has the sense of a reclusive person letting down his guard just a bit. “You could hear the vulnerability in the music before,” he agrees, “but there was such a shield, such a f–k-you to the world, and now I’m very comfortable with letting the world know that I can be that way.”

Press-shy artists are often awkward, defensive, tight-lipped or all three, but even in a setting like this — where he’s a sitting duck for probing personal questions about the seemingly heart-spilling songs that are playing at chest-rattling volume — Weeknd is easygoing and downright chatty. If he can’t or doesn’t want to explain the emotions behind a certain song, he’ll either demur or say he doesn’t really know, explaining later, “It’s easier to talk about songs that are just about me; I don’t like to talk about what I’m going through with other people.”

The conversation also provides inadvertent glimpses into his life. When “Scared to Live,” with its interpolation of Elton John’s “Your Song” refrain “I hope you don’t mind” comes up, he says, “Before I played it for Elton, I was like, ‘F—, I hope he likes it.’ But he was freakin’ — he was like, ‘Mate, you’re gonna be doing this for a long time!’”

Asked whether such moments happen often, he turns a little sheepish. “No, man! This whole album process has been so surreal, in the best way possible.”

For his part, Elton John tells Variety, “Abel has his own unique artistic voice — that’s the hallmark of a genuinely great, long-term artist. I’m utterly thrilled that the DNA for ‘Your Song’ has found its way into ‘Scared to Live.’ It’s the greatest compliment a songwriter can ever receive.”

However, later on the new album, “Faith,” with its lyrical references to drugs, pain, prayer, death and “losing my religion,” raises many serious questions. He waits until the song ends before responding. “So, this is about the darkest time of my entire life, around 2013, 2014,” when he first became famous. “I was getting really, really tossed up and going through a lot of personal stuff. I got arrested in Vegas [for punching a police officer; he later pleaded no contest]. It was a real rock-star era, which I’m not really proud of. You hear sirens at the end the song — that’s me in the back of the cop car, that moment.

“I always wanted to make that song but I never did, and this album felt like the perfect time, because [the character] is looking for an escape after a heartbreak or whatever. I wanted to be that guy again — the ‘Heartless’ guy who hates God and is losing his f—ing religion and hating what he looks like in the mirror so he keeps getting high. That’s who this song is.”

People spend their entire lives trying to escape their demons; not many decide to revisit them.

“I didn’t want to,” he says. “But sometimes you try to run away from who you are, and you always get back to that place. By the end of this album, you realize, ‘I’m not that person.’ I was, but I’m growing and wiser, and I’m gonna have children someday, and I’m going to tell them they don’t have to be that person.”

And yes, his recent birthday milestone enabled him to come to this — “self-realization,” he says, completing the sentence. “I think people say your 30s are your best years because you’re becoming the person you’re supposed to be. And this is the beginning of not just a new chapter but my second decade [as a performer]. I feel like my career is just starting.”

Every element of The Weeknd’s background is present in his music. Born in 1990 to Ethiopian immigrants who split up when he was a toddler, he grew up trilingual in a multicultural neighborhood outside Toronto filled with fellow East Africans as well as people from India, the Middle East and the Caribbean.

“Ethiopian — Amharic — was the first language I learned to form sentences in because my grandma, who raised me with my mom, would not speak English,” he says. “Because of television and being in Canada, I learned English too, but I went to French-immersion school, where you’d get in trouble for speaking English, and I couldn’t speak it to my grandma, so it’s almost like English is my third language, even though now it’s my first.”

The music in his home was a combination of Ethiopian artists like Aster Aweke — “Her voice was very influential on my singing; you can hear it, for sure,” he says — and R&B like Michael Jackson and R. Kelly. After his pivotal experience with “The Mask,” he gradually became a full-on movie geek and hoped to attend film school. “I didn’t know that I had a gift with music, but I was always singing. I was actually getting in trouble because I would sing in class — my poor mother, it became a real problem,” he sighs. “I was really shy so I wasn’t really singing to my friends or girls, but when I was maybe 13, somebody said, ‘You actually have a pretty nice voice.’”

La Mar Taylor, Weeknd’s longtime friend and creative director, remembers things slightly differently. “I met Abel on the very first day of high school,” he recalls. “He was charismatic, witty and gave no f—s on how people perceived him.”

Weeknd’s rough-and-tumble youth, which included a brief stretch of homelessness and a long stretch of substance abuse (ketamine, cocaine, Ecstasy, cough syrup) is directly addressed in the opening lyrics of the plainly autobiographical “Snowchild,” from “After Hours”: “I used to pray when I was 16 / If I didn’t make it, then I’d probably make my wrist bleed. … I was singing notes while my n—as played with six keys [kilos]. … N—as had no homes, we were living in the dead streets.”

“It was tough growing up where I was from,” he says of those years. “I got into a lot of trouble, got kicked out of school, moved to different schools and finally dropped out. I really thought film was gonna be my way out, but I couldn’t really make a movie to feel better, you know? Music was very direct therapy; it was immediate and people liked it. It definitely saved my life.”

With “House of Balloons,” the groundbreaking mixtape that thrust Weeknd onto the music scene early in 2011, the young artist seemed to arrive fully formed. Powered by a co-sign from Drake’s management team (which soon led to a musical collaboration, and later a schism, with his fellow Torontonian), its unusual mixture of influences — classic R&B, electronic music, ’80s pop, Kanye West’s metrosexual hip-hop and particularly Michael Jackson’s 1987 song “Dirty Diana,” which he describes as “the blueprint to my music” — rapidly gained him a large audience and a major-label deal with Republic, a subsidiary of Universal Music Group.

Still, the mixtape’s dark, murky sound was like nothing else at the time, and it tied in with the launch of Weeknd’s equally moody mystique: The drug-addled, womanizing, bitter character in the songs matched the artist who initially didn’t do interviews, hadn’t performed live and was seldom photographed.

The Weeknd’s sound didn’t remain unique for long. Within months, moody alt-R&B was everywhere. “‘House of Balloons’ literally changed the sound of pop music before my eyes,” he says without exaggeration. “I heard ‘Climax,’ that [2012] Usher song, and was like, ‘Holy f—, that’s a Weeknd song.’ It was very flattering, and I knew I was doing something right, but I also got angry. But the older I got, I realized it’s a good thing.”

His initial concerts displayed growing pains as well, so he took dancing lessons and amped up his live show, and, most significantly, he unleashed the latent Michael Jackson in his high, angelic singing voice. It seemed like an instant transformation, but it wasn’t. “People saw the rise but have no idea how hard Abel and our small team worked for years before we got the recognition,” Slaiby says. “Abel created this whole new R&B wave everyone is on now.”

Key to his breakout were the hits he created with Max Martin, with whom he teamed initially on a 2014 collaboration with Ariana Grande, “Love Me Harder.”

“Ariana was kinda my foot in the door with Max, my chance to show him ‘I can play this game,’ y’know?” he recalls. “But when we got in the room together, we didn’t really connect as much. Then someone invited him to a show I did at the Hollywood Bowl, and he saw 15,000 people singing along, and I think he was like, ‘OK, there’s something I’m not getting.’ So we sat down again, and the first song we created was ‘In the Night.’” That song and “Can’t Feel My Face,” an even bigger Martin collaboration from the 2015 album “Beauty Behind the Madness,” became global smashes and vaulted Weeknd into the pop stratosphere, a status he cemented with the follow-up, 2016’s triple-platinum “Starboy.”

But although Weeknd has collaborated with some of the biggest names in music — Beyonce, Kanye West, Drake, Ed Sheeran, Kendrick Lamar, Daft Punk, Lana Del Rey and Travis Scott, among many others — the kind of true collaboration he has with Martin is neither common nor easy.

“Max and I have become literally the best of friends, but I don’t do that with many people,” he says. “It’s not that I can’t, but a collaboration is a relationship, it’s like a marriage, you’ve gotta build up to it. Lana is another collaborator who’s a genuine friend of mine.”

However, when asked about the pioneering French electronic-music duo Daft Punk — whose two collaborations drove “Starboy,” Weeknd’s 2016 follow-up to “Beauty Behind the Madness,” to triple-platinum status — his voice takes on tones of awe. “Oh my God, that’s different,” he says. “Those guys are one of the reasons I do this. I didn’t even care if we made music, I just wanted to be friends with them, and that’s how it started — I met them out partying in L.A. But then we went into the studio in Paris and did both ‘Starboy’ and ‘I Feel It Coming’ in the span of four days.”

After releasing two blockbuster albums in consecutive years, the wise pop star lays low to avoid oversaturation. For the workaholic Weeknd, his “hiatus” consisted of two tours; a comparatively low-key EP, 2018’s “My Dear Melancholy”; and years of work on “After Hours.”

“He has a work ethic like I’ve never seen before, and over time that ethic only got stronger with the responsibilities that come with being a superstar,” Esmailian says. “We call him ‘The Machine’ because he’s always working.”

In March 27, one week after the release of “After Hours,” The Weeknd is at home in Los Angeles, doing pretty much the same things as virtually every other sane, nonessential adult in the First World: sheltering in place, binge-watching TV (“Peaky Blinders,” “Shameless,” “Mindhunter”), getting to know his dog, Caesar, better (“I feel like we’re speaking a new language”) and working as much as possible toward When This Is Over, whenever that may be.

“I’m always sitting inside working, so it’s not that different from any other day,” he says over FaceTime. “Although I am a contrarian, and I don’t like being told what to do, so not being able to go out is tough. But music is therapy, thank God I’ve got that.”

While 10 days earlier he was still confident the nearly sold-out “After Hours” tour would proceed as planned, of course it’s been bumped indefinitely. “The tour is still happening — we’re not canceling,” he stresses. “We just have to rearrange the dates, which is unfortunate but certainly understandable.”

But the “overwhelming, in a good way” reaction to the album — exemplified by thousands of social media comments, like “My quarantine is now less terrible” and “Weeknd, thank you for giving us something beautiful in this horrible time” — has only affirmed his decision not to delay it. “It’s been amazing to see the real heroes in our world: health care workers, grocery store clerks, first responders,” he says. “If I could do something even as small as taking people away from what’s happening in the world for an hour, then what better time?”

Without overstating its importance, for better or worse, “After Hours” will always be associated with this moment. And while its songs may immediately bring back the horror of March 2020 — even more, they might remind people of the desperately needed uplift that those songs brought amid the madness.

( Head here for a long interview with The Weeknd about the album, its concept, videos, creation and more .)