Fantasia Film Review: ‘The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then The Bigfoot’

By Dennis Harvey

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – Rarely has the gap between outlandish concept and pedestrian execution been quite so wide as it is with “The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then The Bigfoot.” Producer Robert D. Krzykowski’s long-aborning debut feature as writer-director must’ve had a passion project’s motivation behind it to reach realization. Yet it’s difficult from the final result to fathom just what the intended point was.

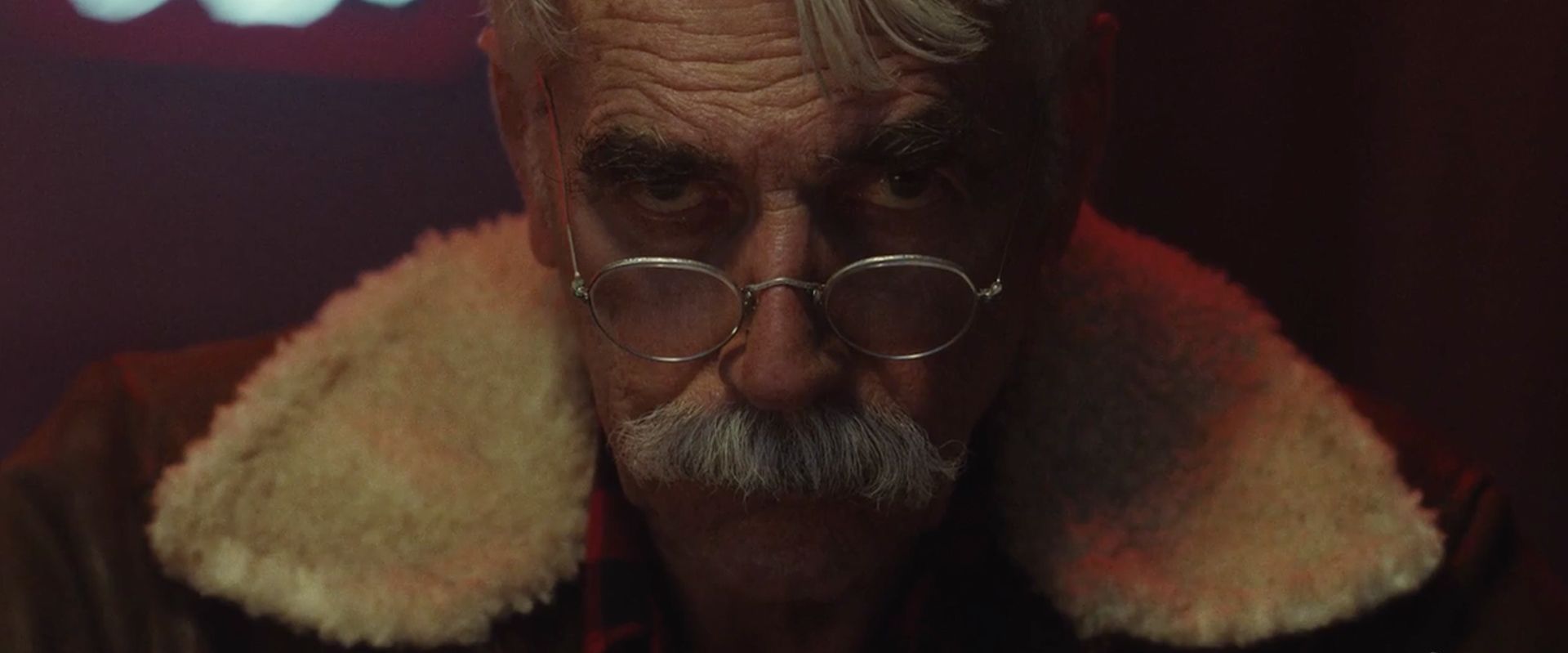

All its idiosyncrasy expended on that undeniably head-turning title, this low-key, literal-minded indie manages to make those marquee events pretty uninteresting. The rest is a surprisingly rote grumpy-old-coot character study that provides Sam Elliott another opportunity to amble respectably through a portrait of late-life discontent not so different from last year’s tepid “The Hero.”

Whatever expectations of a goofy and/or fantastical good time raised by that memorable moniker will go unfulfilled by a movie whose imagination seemingly ran dry after the title page was written. Commercial placements are going to be an uphill climb.

After an opening that teases the first of the two billed happenings here, we meet Elliott’s protagonist, Calvin Barr, a man of few words and no apparent job or family ties (save Larry Miller as younger brother Ed). Spending yet another evening on a small-town barstool, he’s halted on the way home by three would-be carjackers, giving him a chance to demonstrate that this old man can still kick butt when riled.

Such physical resiliency appears to have already been noted by the FBI official (Ron Livingston) and Canadian government representative (Rizwan Manji) who land on Calvin’s door shortly thereafter. Despite his age, his tracking ability as an ex-spy and apparent rare blood immunity have made him the only viable candidate for a top-secret mission: killing Bigfoot. That fabled creature not only exists, but has fallen ill with some “nightmare plague” that could potentially wipe out all earthly life if its carrier isn’t destroyed. For this purpose, the initially reluctant Barr must journey solo into a 50-square-mile zone of quarantined Canuck wilderness.

When that quest finally commences, the film kicks into higher gear, albeit all too briefly. But throughout we get flashbacks to our hero’s long-ago prior assassination commission, when he used his skills as a multilinguist to infiltrate Nazi Germany and kill Der Fuhrer.

This is all pretty exciting, outré stuff … or so you would think. But it’s typical of the film’s odd, cardboard, comic-book take on history that when young Calvin (Irish thesp Aidan Turner of the “Poldark” series and “Hobbit” films) finally succeeds in his WW2 mission, we’re told it didn’t much matter because Germany came up with replacement “Hitlers” anyway.

Similarly, other key narrative threads trail off into nothingness. Taking up a great deal of bland screen time is the generic pre-war romance Calvin has with schoolteacher Maxine (Caitlin Fitzgerald). That relationship’s loss seemingly embittered him for the rest of his life, yet Krzykowski inexplicably can’t be bothered to explain just why or how his love object died prematurely.

There are other strange lapses of scripting logic that might’ve passed as delightful quirks in a different movie, but here they seem to have been omitted through some mix of neglect and disinterest. What is Krzykowski interested in? It’s hard to tell. In part he seems to be creating a paean to an old-school heroic masculinity, at once modest, merciless, and very American. His two lead actors can embody that kind of archetype nimbly enough. But there’s no real connection between the aw-shucksy, tongue-tied young Calvin who courts Maxine, and the one who calmly sneaks across Europe to kill Hitler — or the older version who requires only a couple of weapons and some backpacking gear to slay Bigfoot. These one-dimensional protagonists don’t credibly evolve into one another, leaving a gaping 50-year psychological gap between them.

Though there are glimmers of humor here (the best visual gag being a Nazi watch with a swastika where the hands should be), this is mostly a bewilderingly earnest enterprise — a character drama sans depth, propped up by fantastical incidents depicted without much verve or absurdism. One can adjust to its being a mild movie with a wild title, but it’s not even a particularly good mild film. Your average Hallmark Movie might realize Krzykowski’s principal elder-angst themes for a suitable senior star with greater insight — though of course we wouldn’t get guest stars Adolf and Sasquatch.

The result is a puzzlingly innocuous curio with unconvincing period atmospherics, OK performances by under-utilized cast members, the occasional lively moment (most on the Bigfoot trail), and far too little eccentricity for a movie with this title. Acceptably crafted in most tech/design departments yet without much personality, “The Man Who Killed Hitler…” is the equivalent of a bowl of tapioca — a warm mush that tastes all wrong when you thought you’d ordered chili con carne, heavy on the hot sauce.