‘Be Water’: Film Review

By Dennis Harvey

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – Some movie stars level a kind of divinity that transcends personal preference — woe betide the dissenter who openly finds Audrey Hepburn cloying, or Cary Grant less than charming. That Bruce Lee had long ascended to that level of iron-clad cool was underlined by the biggest popular quibble with “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood,” over the single scene when Mike Moh’s fictive Lee is portrayed as an arrogant, bullying jerk easily whupped by Brad Pitt’s stuntman Cliff. To many, this jokey bit wasn’t just mockery of a beloved dead celebrity — it was tantamount to blasphemy.

“Live From New York!” director Bay Nguyen’s new “Be Water” helps explain the vehemence of that reaction, positing the late “kung fu movie” superstar as not just a singular charismatic talent but a game changer who singlehandedly broke the mold of hitherto stereotypical, largely negative Asian portrayals on Western screens. . Producer ESPN is purportedly mulling limited theatrical release prior to broadcast exposure.

“Be Water” was posited at Sundance as focusing on the two years Lee spent in Hong Kong, filming four features that would make him a global sensation. But that’s just one section of a beginning-to-end life and career overview told entirely through archival materials, with reminiscences from co-workers, family members and such limited to the audio track.

It does tease that period at the beginning, showing how Lee accepted an offer to make a low-budget HK action movie, having despaired that Hollywood would ever relax its racial casting barriers for him. “The Big Boss” (1971) made him an instant smash with local audiences, allowing the next year’s follow-up, “Fist of Fury,” to sport period trappings and greater resources overall. “Be Water” then jumps back a dozen years to Lee’s arrival in the U.S. — where he’d been born while his Chinese opera star father was on tour in 1940, though then raised in Hong Kong. He was a successful child actor, yet so unruly that at age 18 he was sent back overseas by his parents in the hopes that being alone with few resources would straighten him out.

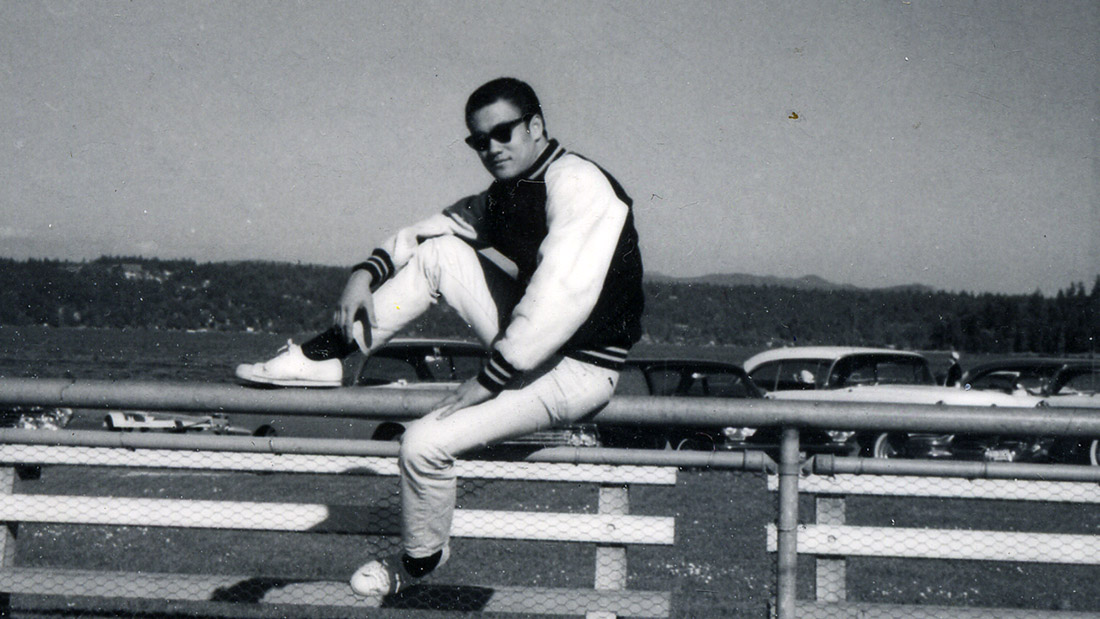

Settling in Seattle, he began teaching his own increasingly individual form of traditional Chinese martial arts, eventually modified by influences as far-ranging as Muhammad Ali’s boxing style. Participation in an L.A. tournament caught the entertainment industry’s attention, and he soon abandoned his dream of opening nationwide gung fu schools for a new one of (renewed) movie stardom, figuring that would provide a faster way of changing Asian Americans’ subservient “model minority” image anyway.

But he had to fight for dialogue and a more active role as sidekick Kato on short-lived TV series “The Green Hornet.” Subsequent acting offers were few, despite his acquiring such A-list clients as Steve McQueen, James Coburn and James Garner. The final straw came when primetime drama “Kung Fu,” whose concept he purportedly came up with (there are conflicting opinions on the matter), wound up starring Caucasian actor David Carradine as a Shaolin monk in the Old West, rather than Lee himself.

Ergo he accepted upstart studio Golden Harvest’s offer of a starring feature role, moving wife Linda and their two children to Hong Kong. They came to feel trapped there by the magnitude of his fan-hounded fame, yet it still took a while for Hollywood to register the phenomenon. (In the meantime, Lee wrote and directed his third film there, “The Way of the Dragon,” which featured a strong anti-imperialist theme at a time of protests against British rule.) Finally Warner Bros. offered a crossover vehicle in “Enter the Dragon,” which, despite his initial unhappiness with the script, would become a massive success everywhere, including the U.S. Sadly, he died of an apparent cerebral edema just days before it premiered.

Though there would be many imitators (including a few who opportunistically used variants on his name), there would never be another . In pristine clips from his films here, he remains riveting — coiled stillness erupting into sudden, lethal yet graceful movement, his acting in admittedly two-dimensional roles as engagingly confident as those fighting moves. Though later martial arts specialists like Sonny Chiba and Jackie Chan would also acquire international followings, Lee paved their way to Western audiences. Given his creative ambition, it is fascinating to ponder what else he might have achieved in a career that was really just beginning when it was abruptly snuffed out.

Those expecting detailed insight into the making of his prime vehicles may be a tad disappointed at their rather cursory treatment here, amid what amounts to a conventional (if non-chronologically structured) birth-to-death biopic. But the ample archival footage — which includes a surprising wealth from his pre-Hollywood years — is absorbing, and the audio input from surviving associates interesting if seldom revelatory. They, including widow Linda, brother Robert, daughter Shannon, co-stars Nancy Kwan and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and many more (though “Way of the Dragon’s” Chuck Norris is notably absent) are shown as they are today only during the final identifying credits. Assembly is straightforwardly high-grade throughout, with film and TV excerpts used mostly in fine condition.