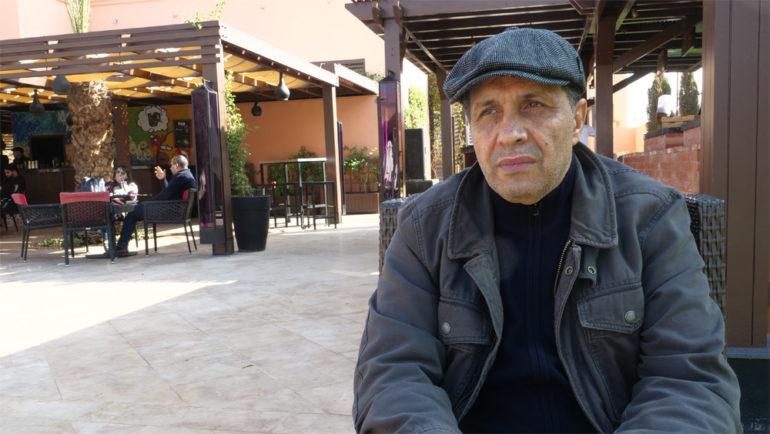

Moroccan Director Nour-Eddine Lakhmari on Documentary ‘Turn the Light On,’ and New Feature

By Martin Dale

LOS ANGELES (Variety.com) – Moroccan director Nour-Eddine Lakhmari – whose trilogy of films, “Casanegra,” “Zero” and “Burnout,” were major local hits – is completing a documentary for the Marrakech Film Festival Foundation, entitled “Turn the Light On,” about the Foundation’s medical-social campaign, that provides free cataract surgery treatment.

The campaign is organized in partnership with the Ministry of Health and the Hassan II Foundation of Ophthalmology and has been in existence since 2009. Lakhmari filmed 310 operations in one week.

A 6-minute teaser from the documentary will be screened in the closing ceremony of the on Saturday. The final 45-minute version will be released in early 2020.

Lakhmari is also preparing a new feature film about a young woman who runs away from home and moves to a remote village in Morocco. This marks a significant break from the style and themes of his previous films, which revolved around strong male protagonists, street violence and were all lensed in Casablanca.

Lakhmari attributes this new approach to his recent life experiences, including making the documentary.

“Turn the Light On” follows the journey of a group of ophthalmologists from Rabat who travel to poor villages in the Moroccan interior where they provide free eye treatment.

Lakhmari filmed the entire journey including the operations and the local people’s reactions.

“After the operation, several people said ‘Thanks be to God,’ because they felt that the doctors were almost like God’s messengers, bringing His light to them,” explains the helmer.

He says that it was profoundly moving to accompany the doctors, who come from well-off neighborhoods, and traveled long distances and slept in humble abodes in the villages, to help people with virtually no personal possessions.

Remote mountain villages in Morocco often have a high level of in-breeding which causes genetic disorders that can affect people’s eyesight. Poverty also increases the frequency of cataracts.

Lakhmari asked one of the doctors why he volunteers for this social campaign and he replied: “If I don’t do this I will die as a human being. I need to help these people. I need to feel these human connections.”

Situations shown in the film include a grandfather who has never seen his granddaughter, and suddenly regains his sight, and a woman who hasn’t seen her near-blind mother for many years and travels 400 miles to a remote village where her mother is operated on, and says, “Finally the doors will no longer hit me, the walls won’t hit me.”

Lakhmari says that working on this project has had a profound effect on his outlook on both life and the cinema.

“After completing ‘Burnout’ in 2017, I thought a great deal. My fellow generation of filmmakers, colleagues like Laila Marrakchi, Narjiss Nejjar, Faouzi Bensaïdi, came back to Morocco after spending many years in Europe. I think we were part of a broader Movida social movement, as the country embraced new freedoms. We wanted to use the language spoken by people in Morocco – darija – in our films. We wanted to denounce many things, often in a direct, sometimes brutal way. We were angry. But now it’s time for the new generation to denounce injustices, in their own way. I’m looking for a new approach.”

He believes that the new generation of women filmmakers, who are following in the footsteps of helmers such as Marrakchi and Nejjar, are injecting new energy into Moroccan cinema. He cites examples such as Meryem Benm’barek, whose debut feature “Sofia” won the screenplay award in Un Certain Regard in Cannes in 2018, and Maryam Touzani, whose debut feature “Adam” screened in Un Certain Regard this year, and is Morocco’s International Oscar nomination.

“Over the last three to four years we have seen the rise of a new generation of Moroccan female filmmakers who are talking about women without taboos, without placing them in the role of the victim, who say ‘How can I be free without having control over my body?’”

Subjects such as abortion have come into the spotlight in Morocco in 2019 and Lakhmari believes that films by women directors are playing a key role in changing mentalities.

“The underlying problem is always the relationship between man and woman. If you have free women you have a free society.”

Lakhmari aims to channel these influences into his next project, which he is currently writing, about a young woman who lives in Casablanca and runs away from home, to escape from her overbearing father and moves to a Berber village in the Atlas mountains. She interacts with the local villagers and challenges what she considers to be patriarchal ideas and traditions.

The helmer hopes to shoot the feature in 2020 and concludes: “Men in Morocco are scared, because women are moving so fast. But if we want more freedom in our country it will be through our women.”